Product Overview

Pregnenolone cream represents a specialized compounded pharmaceutical preparation containing pregnenolone as the primary active ingredient, formulated for topical application in a 100 mg/mL concentration within a 30 mL container. This neurosteroid compound serves as a precursor molecule in the biosynthesis of various steroid hormones and has garnered significant attention in clinical practice for its potential therapeutic applications across multiple physiological systems.[1] Pregnenolone, often referred to as the “mother of all hormones,” occupies a central position in steroidogenesis, serving as the initial substrate from which numerous other hormones are synthesized, including progesterone, cortisol, aldosterone, testosterone, and estrogens.[2]

The compounded nature of pregnenolone cream allows for customized dosing and delivery methods that may not be available through conventional pharmaceutical manufacturing processes. Healthcare practitioners may prescribe this formulation when seeking to address specific patient needs that cannot be adequately met by commercially available products.[3] The topical route of administration potentially offers advantages over oral delivery, including reduced first-pass hepatic metabolism, more localized tissue distribution, and the possibility of achieving therapeutic tissue concentrations while minimizing systemic exposure.[4]

Clinical interest in pregnenolone has expanded considerably as research continues to elucidate its diverse physiological functions beyond its role as a steroid precursor. The compound demonstrates direct biological activity through interaction with various neurotransmitter systems, particularly gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, suggesting potential applications in neurological and psychiatric conditions.[5] Additionally, pregnenolone may influence cognitive function, mood regulation, and stress response mechanisms through both its direct actions and its conversion to downstream metabolites.[6]

The formulation of pregnenolone as a topical cream requires careful consideration of pharmaceutical factors including penetration enhancement, stability, and bioavailability. Compounding pharmacies must employ specialized techniques to ensure uniform distribution of the active ingredient throughout the cream base while maintaining chemical stability throughout the product’s shelf life.[7] The selection of appropriate excipients and cream base components plays a crucial role in determining the product’s therapeutic efficacy and patient tolerability.[8]

Regulatory oversight of compounded pregnenolone cream falls under section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which governs traditional pharmacy compounding practices. This regulatory framework ensures that compounded preparations meet specific quality standards while allowing for the customization necessary to address individual patient needs that cannot be met by FDA-approved commercial products.[9] Healthcare providers prescribing pregnenolone cream must carefully evaluate each patient’s clinical circumstances and monitor treatment outcomes to optimize therapeutic benefits while minimizing potential risks.[10]

Pregnenolone cream dosage and administration protocols must be individualized based on patient-specific factors, including the indication for treatment, patient age, body surface area, concurrent medications, and clinical response to therapy.[73] The standard formulation provides 100 mg/mL concentration in a 30 mL container, allowing for precise dosing adjustments according to clinical needs. Healthcare providers should initiate treatment with the lowest effective dose and gradually titrate based on therapeutic response and tolerability.[74]

The typical starting dose for pregnenolone cream ranges from 0.25 mL to 0.5 mL applied topically once or twice daily, providing approximately 25 to 50 mg of pregnenolone per application.[75] The specific dosage should be determined based on the patient’s clinical condition, severity of symptoms, and individual response to treatment. Some patients may require higher doses, up to 1 mL per application, while others may achieve therapeutic benefits with lower doses.[76] Dose escalation should be performed gradually, with increases of 0.25 mL every 1-2 weeks as tolerated and clinically indicated.

Application technique plays a crucial role in optimizing therapeutic outcomes and minimizing local adverse effects.[77] The cream should be applied to clean, dry skin areas with good vascular supply to enhance absorption, such as the inner wrists, inner arms, or torso areas. Patients should be instructed to apply the cream using gentle rubbing motions until fully absorbed, avoiding application to broken, irritated, or damaged skin surfaces.[78] The application site should be rotated regularly to prevent local irritation and ensure consistent absorption patterns.

Timing of administration may influence therapeutic efficacy, as natural pregnenolone production follows circadian rhythms with peak concentrations occurring in the early morning hours.[79] Many healthcare providers recommend morning application to align with physiological patterns, although individual patient responses may warrant alternative timing schedules. For patients receiving twice-daily dosing, applications should be spaced approximately 12 hours apart to maintain consistent tissue concentrations.[80]

Patient education regarding proper application techniques, dose measurement, and monitoring for therapeutic effects and adverse reactions is essential for treatment success.[81] Patients should be provided with appropriate measuring devices and detailed instructions for accurate dose preparation. The importance of consistent application timing, proper storage conditions, and adherence to prescribed dosing schedules should be emphasized during patient counseling sessions.[82]

Dose adjustments may be necessary based on clinical response, laboratory monitoring results, and the development of adverse effects.[83] Healthcare providers should establish regular follow-up schedules to assess treatment efficacy and safety, typically every 4-6 weeks during initial treatment phases and every 3-6 months during maintenance therapy. Laboratory monitoring may include hormone level assessments, liver function tests, and other parameters as clinically indicated.[84]

Pregnenolone exerts its therapeutic effects through multiple interconnected biochemical pathways, beginning with its fundamental role as the initial steroid hormone precursor synthesized from cholesterol through the action of cytochrome P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme.[11] This enzymatic conversion represents the rate-limiting step in steroidogenesis and determines the availability of pregnenolone for subsequent hormone synthesis pathways. The compound’s mechanism of action encompasses both its direct pharmacological effects on cellular targets and its indirect effects mediated through conversion to downstream steroid metabolites.[12]

At the molecular level, pregnenolone demonstrates direct modulation of neurotransmitter receptor systems, particularly serving as a positive allosteric modulator of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors, thereby enhancing inhibitory neurotransmission.[13] This interaction contributes to its potential anxiolytic and neuroprotective properties. Conversely, pregnenolone acts as a negative modulator of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, potentially influencing excitatory neurotransmission and contributing to its cognitive enhancement effects.[14] These dual mechanisms suggest that pregnenolone may help maintain optimal neural excitability balance.

The compound also influences the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis through complex feedback mechanisms, potentially modulating stress response and cortisol production patterns.[15] Pregnenolone may compete with cortisol for binding to glucocorticoid receptors, potentially providing protective effects against excessive glucocorticoid activity during chronic stress conditions.[16] This mechanism could contribute to its reported benefits in stress-related disorders and cognitive dysfunction associated with elevated cortisol levels.

Topical application of pregnenolone cream allows for localized tissue distribution while potentially avoiding extensive hepatic first-pass metabolism that occurs with oral administration.[17] The transdermal delivery system may facilitate direct tissue uptake and local conversion to active metabolites within target tissues, potentially enhancing therapeutic efficacy while reducing systemic exposure.[18] Skin metabolism of pregnenolone through local enzyme systems may contribute to the formation of bioactive compounds that exert beneficial effects on skin health and barrier function.[19]

Pregnenolone’s conversion to progesterone through 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase represents one of its most clinically relevant metabolic pathways, particularly in reproductive tissues.[20] This conversion may contribute to hormonal balance restoration in individuals with progesterone deficiency states. Additionally, pregnenolone can serve as a precursor for dehydroepiandrosterone synthesis, which may influence immune function, bone metabolism, and cardiovascular health.[21] The relative distribution of pregnenolone among these various metabolic pathways may depend on tissue-specific enzyme expression patterns and local hormonal requirements.[22]

Pregnenolone cream is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity or allergic reactions to pregnenolone or any components of the cream formulation, including excipients and preservatives commonly used in topical preparations.[23] Allergic reactions may manifest as contact dermatitis, urticaria, or more severe systemic hypersensitivity responses that could potentially compromise patient safety. Healthcare providers must carefully evaluate patients for previous adverse reactions to steroid compounds or similar topical medications before initiating treatment.[24]

Patients with hormone-sensitive malignancies, particularly breast cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, or prostate cancer, should not use pregnenolone cream due to the potential for steroid hormone conversion and subsequent stimulation of hormone-dependent tumor growth.[25] The compound’s ability to serve as a precursor for various steroid hormones, including estrogens and androgens, creates theoretical risks for promoting tumor progression in susceptible individuals.[26] Even though pregnenolone itself may not directly stimulate hormone receptors, its metabolic conversion products could potentially influence cancer cell proliferation and survival.

Pregnancy represents an absolute contraindication for pregnenolone cream use due to insufficient safety data regarding fetal exposure and potential teratogenic effects.[27] The developing fetus demonstrates particular sensitivity to hormonal influences, and exogenous steroid administration during pregnancy could potentially disrupt normal fetal development patterns. Additionally, pregnenolone’s ability to cross placental barriers and influence fetal steroidogenesis pathways creates unacceptable risks for adverse pregnancy outcomes.[28]

Breastfeeding mothers should avoid pregnenolone cream application due to the potential for systemic absorption and subsequent excretion into breast milk, which could expose nursing infants to steroid compounds during critical developmental periods.[29] The immature hepatic and endocrine systems of infants may be unable to appropriately metabolize or eliminate steroid compounds, potentially leading to hormonal disruption or other adverse effects.[30]

Patients with severe hepatic impairment or active liver disease should not use pregnenolone cream, as the liver plays a central role in steroid hormone metabolism and clearance.[31] Compromised hepatic function could lead to altered pregnenolone metabolism, accumulation of active metabolites, and increased risk of adverse effects. Additionally, individuals with severe renal impairment may experience altered steroid hormone clearance patterns that could necessitate dosage modifications or treatment discontinuation.[32]

Active thromboembolic disorders or a history of recurrent thromboembolism represent relative contraindications for pregnenolone cream use, particularly given the potential for steroid metabolites to influence coagulation pathways and thrombotic risk.[33] Patients with underlying coagulopathies or those receiving anticoagulant therapy require careful risk-benefit assessment before initiating treatment with any steroid hormone preparation.[34]

Pregnenolone cream may interact with various medications through multiple mechanisms, including competition for metabolic enzymes, alteration of protein binding, and modulation of receptor activity.[35] Healthcare providers must carefully evaluate all concurrent medications and supplements when prescribing pregnenolone cream to minimize the risk of clinically significant drug interactions. The topical route of administration may reduce some systemic drug interaction risks compared to oral pregnenolone, but significant interactions remain possible due to systemic absorption.[36]

Cytochrome P450 enzyme systems, particularly CYP3A4, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6, play crucial roles in steroid hormone metabolism and may be influenced by pregnenolone administration.[37] Medications that inhibit or induce these enzyme systems could potentially alter pregnenolone metabolism and the formation of active metabolites. Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as ketoconazole, clarithromycin, and grapefruit juice, may increase pregnenolone bioavailability and enhance the risk of adverse effects.[38] Conversely, CYP3A4 inducers like rifampin, carbamazepine, and St. John’s wort may accelerate pregnenolone metabolism and reduce therapeutic efficacy.[39]

Concurrent use of other steroid hormones or hormone replacement therapies may result in additive or synergistic effects that could lead to hormonal imbalances or adverse reactions.[40] Estrogen-containing medications, testosterone preparations, and corticosteroids may interact with pregnenolone metabolites at the receptor level or through shared metabolic pathways. Patients receiving thyroid hormone replacement therapy may require monitoring for potential interactions, as thyroid hormones can influence steroid hormone metabolism and binding protein synthesis.[41]

Anticoagulant medications, including warfarin, heparin, and direct oral anticoagulants, may demonstrate altered efficacy when used concurrently with pregnenolone cream.[42] Steroid hormones can influence the synthesis of clotting factors and anticoagulant proteins, potentially affecting coagulation parameters and bleeding risk. Regular monitoring of coagulation studies may be necessary for patients receiving both pregnenolone and anticoagulant therapy.[43]

Central nervous system medications, particularly those affecting gamma-aminobutyric acid or glutamate neurotransmission, may demonstrate enhanced or reduced effects when combined with pregnenolone.[44] Benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and other GABAergic medications could potentially show increased sedative effects due to pregnenolone’s positive modulation of GABA receptors. Conversely, medications that enhance glutamate activity may experience reduced efficacy due to pregnenolone’s NMDA receptor antagonism.[45]

Insulin and other antidiabetic medications may require dosage adjustments in patients using pregnenolone cream, as steroid hormones can influence glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity.[46] Regular blood glucose monitoring may be necessary to detect changes in glycemic control and adjust antidiabetic therapy accordingly. Additionally, medications that undergo significant hepatic metabolism may experience altered pharmacokinetics due to pregnenolone’s potential effects on hepatic enzyme systems.[47]

Pregnenolone cream may produce various side effects ranging from mild local reactions to more significant systemic manifestations, although the topical route of administration generally results in lower incidence and severity of adverse effects compared to oral administration.[48] Healthcare providers should educate patients about potential side effects and establish appropriate monitoring protocols to ensure early detection and management of any adverse reactions. The development of side effects may depend on factors including dosage, duration of treatment, individual patient sensitivity, and concurrent medications.[49]

Local skin reactions represent the most commonly reported side effects associated with topical pregnenolone cream application.[50] These reactions may include erythema, itching, burning sensation, dryness, or irritation at the application site. Contact dermatitis may develop in sensitive individuals, potentially manifesting as localized inflammation, vesicle formation, or skin peeling.[51] Patients should be instructed to discontinue use and seek medical attention if severe local reactions occur or if mild reactions persist beyond the initial adaptation period.

Systemic absorption of pregnenolone through the skin may lead to hormonal effects that could manifest as mood changes, including irritability, anxiety, restlessness, or mood swings.[52] Some patients may experience alterations in sleep patterns, including difficulty falling asleep, frequent awakening, or changes in dream activity. These neurological effects may be related to pregnenolone’s interaction with neurotransmitter systems and its conversion to other neuroactive steroids.[53]

Endocrine-related side effects may occur due to pregnenolone’s role as a steroid hormone precursor and its potential conversion to various active metabolites.[54] Women may experience menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, or changes in libido. Men might notice alterations in sexual function, voice changes, or breast enlargement. These effects typically reflect the influence of pregnenolone metabolites on sex hormone receptors and reproductive function.[55]

Gastrointestinal side effects, while less common with topical administration, may include nausea, abdominal discomfort, or changes in appetite.[56] These effects may be related to systemic absorption and the influence of steroid hormones on gastrointestinal motility and digestive function. Cardiovascular effects, such as changes in blood pressure, heart rate, or fluid retention, may occur in susceptible individuals due to the influence of steroid metabolites on cardiovascular regulatory mechanisms.[57]

Neuropsychiatric effects may include headaches, dizziness, cognitive changes, or alterations in emotional regulation.[58] Some patients may experience increased energy and alertness, while others might notice fatigue or cognitive fog. These effects may be dose-dependent and could vary based on individual differences in steroid hormone sensitivity and metabolism.[59] Long-term use may potentially lead to tolerance or dependence, although such effects have not been well-characterized for topical pregnenolone preparations.[60]

Pregnenolone cream is contraindicated during pregnancy due to insufficient safety data regarding fetal exposure and the potential for adverse developmental outcomes.[61] The use of exogenous steroid hormones during pregnancy poses theoretical risks to fetal development, as the developing fetus demonstrates particular sensitivity to hormonal influences throughout critical developmental periods. Healthcare providers must ensure that female patients of reproductive age understand these risks and implement appropriate contraceptive measures during treatment.[62]

The placental transfer of pregnenolone and its metabolites represents a significant concern, as these compounds could potentially interfere with normal fetal steroidogenesis and endocrine development.[63] The developing fetal endocrine system relies on precisely regulated hormone concentrations and timing for proper organ development, sexual differentiation, and neurological maturation. Exogenous pregnenolone administration could disrupt these delicate processes and lead to developmental abnormalities.[64]

Animal reproductive studies examining pregnenolone safety during pregnancy have produced limited and sometimes conflicting results, making it difficult to establish clear safety parameters for human use.[65] Some studies have suggested potential effects on fetal growth, sexual development, and neurological function, although the relevance of these findings to human pregnancy remains uncertain.[66] The lack of adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women necessitates a cautious approach that prioritizes fetal safety over potential maternal benefits.

Pregnenolone’s role as a precursor to other steroid hormones creates additional concerns regarding fetal exposure to active metabolites.[67] The conversion of pregnenolone to progesterone, cortisol, and other hormones within maternal and fetal tissues could result in elevated concentrations of these compounds in the developing fetus. Such exposures could potentially influence fetal adrenal function, sexual differentiation, and stress response system development.[68]

Women who inadvertently use pregnenolone cream during early pregnancy should discontinue treatment immediately and consult with their healthcare provider for appropriate monitoring and counseling.[69] Although the risk of adverse fetal effects from brief exposure may be low, particularly with topical administration, careful evaluation of the pregnancy and consideration of appropriate monitoring protocols may be warranted.[70] Healthcare providers should document the exposure and consider referral to maternal-fetal medicine specialists if concerns arise.

Preconception counseling for women planning pregnancy should include discussion of pregnenolone cream discontinuation and appropriate timing for treatment cessation before attempting conception.[71] The elimination half-life of pregnenolone and its metabolites should be considered when determining an appropriate washout period before pregnancy attempts. Alternative treatment options that do not pose fetal risks should be explored for women who require ongoing therapy for their underlying conditions.[72]

Proper storage and handling of pregnenolone cream is essential to maintain chemical stability, therapeutic potency, and patient safety throughout the product’s shelf life.[85] The cream should be stored at controlled room temperature, typically between 20-25°C (68-77°F). Exposure to extreme temperatures, either hot or cold, may compromise the chemical integrity of the active ingredient and affect therapeutic efficacy.[86]

Protection from light exposure is crucial for maintaining pregnenolone stability, as photodegradation can lead to the formation of inactive metabolites and reduced therapeutic potency.[87] The cream should be stored in its original container, which is designed to provide appropriate light protection, and should not be transferred to clear or transparent containers. Storage areas should be selected to minimize exposure to direct sunlight or intense artificial lighting.[88]

Moisture control represents another critical factor in pregnenolone cream storage, as excessive humidity can promote microbial growth and chemical degradation.[89] The storage area should maintain relative humidity levels below 60% when possible, and the container should be tightly closed when not in use to prevent moisture ingress. Bathroom storage should be avoided due to the high humidity levels typically present in these environments.[90]

The cream should be kept out of reach of children and pets to prevent accidental ingestion or inappropriate use.[91] Child-resistant packaging may be recommended, particularly in households with young children who might mistake the cream for other topical products. Adult supervision should be maintained during application in pediatric patients if such use is ever considered appropriate.[92]

Handling procedures should emphasize proper hygiene to prevent contamination and maintain product sterility.[93] Patients should wash their hands thoroughly before and after cream application, and clean application techniques should be used to prevent introducing bacteria or other contaminants into the container. Sharing of the medication with other individuals should be strictly prohibited to prevent cross-contamination and inappropriate use.[94]

Disposal of expired or unused pregnenolone cream should follow appropriate pharmaceutical waste management protocols.[95] The cream should not be discarded in household trash or flushed down toilets or drains, as this could lead to environmental contamination. Many communities offer pharmaceutical take-back programs that provide safe disposal options for unused medications.[96] Patients should be educated about proper disposal methods and encouraged to return unused portions to appropriate collection sites.

Transportation considerations include protection from temperature extremes and physical damage during shipping or personal transport.[97] The cream should not be left in vehicles during hot weather or exposed to freezing temperatures during transport. Original packaging should be maintained during transport to ensure product identification and protection.[98]

- Vallée, M., Mayo, W., & Le Moal, M. (2001). Role of pregnenolone, dehydroepiandrosterone and their sulfate esters on learning and memory in cognitive aging. Brain Research Reviews, 37(1-3), 301-312. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00135-7

- Baulieu, E. E. (1996). Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): a fountain of youth? Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 81(9), 3147-3151. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.81.9.8784058

- Ritsner, M. S., & Strous, R. D. (2010). Pregnenolone, dehydroepiandrosterone, and schizophrenia: alterations and clinical trials. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 16(1), 32-44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00118.x

- Singh, C., Liu, L., Wang, J. M., Irwin, R. W., Yao, J., Chen, S., … & Brinton, R. D. (2012). Allopregnanolone restores hippocampal-dependent learning and memory and neural progenitor survival in aging 3xTgAD and nonTg mice. Neurobiology of Aging, 33(8), 1493-1506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.008

- Reddy, D. S. (2003). Pharmacology of endogenous neuroactive steroids. Critical Reviews in Neurobiology, 15(3-4), 197-234. https://doi.org/10.1615/CritRevNeurobiol.v15.i3-4.20

- Corpéchot, C., Young, J., Calvel, M., Wehrey, C., Veltz, J. N., Touyer, G., … & Baulieu, E. E. (1993). Neurosteroids: 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one and its precursors in the brain, plasma, and steroidogenic glands of male and female rats. Endocrinology, 133(3), 1003-1009. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.133.3.8365352

- Lapchak, P. A., Chapman, D. F., Nunez, S. Y., & Zivin, J. A. (2000). Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate is neuroprotective in a reversible spinal cord ischemia model: possible involvement of GABA A receptors. Stroke, 31(8), 1953-1956. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.31.8.1953

- Weill-Engerer, S., David, J. P., Sazdovitch, V., Liere, P., Eychenne, B., Pianos, A., … & Baulieu, E. E. (2002). Neurosteroid quantification in human brain regions: comparison between Alzheimer’s and nondemented patients. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 87(11), 5138-5143. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2002-020878

- Food and Drug Administration. (2013). Guidance for industry: compounding and the FDA questions and answers (revised). Federal Register, 78(45), 14053-14054.

- Schüle, C., Nothdurfter, C., & Rupprecht, R. (2014). The role of allopregnanolone in depression and anxiety. Progress in Neurobiology, 113, 79-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.003

- Miller, W. L. (2007). Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), a novel mitochondrial cholesterol transporter. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1771(6), 663-676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.02.012

- Melcangi, R. C., & Panzica, G. C. (2014). Allopregnanolone: state of the art. Progress in Neurobiology, 113, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.005

- Lambert, J. J., Belelli, D., Peden, D. R., Vardy, A. W., & Peters, J. A. (2003). Neurosteroid modulation of GABA A receptors. Progress in Neurobiology, 71(1), 67-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.09.001

- Wu, F. S., Gibbs, T. T., & Farb, D. H. (1991). Pregnenolone sulfate: a positive allosteric modulator at the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Molecular Pharmacology, 40(3), 333-336.

- Herman, J. P., Figueiredo, H., Mueller, N. K., Ulrich-Lai, Y., Ostrander, M. M., Choi, D. C., & Cullinan, W. E. (2003). Central mechanisms of stress integration: hierarchical circuitry controlling hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical responsiveness. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 24(3), 151-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.07.001

- Rupprecht, R., Reul, J. M., Trapp, T., van Steensel, B., Wetzel, C., Damm, K., … & Holsboer, F. (1993). Progesterone receptor-mediated effects of neuroactive steroids. Neuron, 11(3), 523-530. https://doi.org/10.1016/0896-6273(93)90156-L

- Hadgraft, J., & Lane, M. E. (2005). Skin permeation: the years of enlightenment. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 305(1-2), 2-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.07.014

- Prausnitz, M. R., & Langer, R. (2008). Transdermal drug delivery. Nature Biotechnology, 26(11), 1261-1268. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1504

- Slominski, A., Zbytek, B., Nikolakis, G., Manna, P. R., Skobowiat, C., Zmijewski, M., … & Zouboulia, E. (2013). Steroidogenesis in the skin: implications for local immune functions. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 137, 107-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.02.006

- Payne, A. H., & Hales, D. B. (2004). Overview of steroidogenic enzymes in the pathway from cholesterol to active steroid hormones. Endocrine Reviews, 25(6), 947-970. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2003-0030

- Labrie, F. (2010). DHEA, important source of sex steroids in men and even more in women. Progress in Brain Research, 182, 97-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(10)82004-7

- Nguyen, A. D., Conley, A. J., & Sneyd, J. (2009). Optimal hormone replacement therapy: a mathematical model for the management of menopause. PLoS One, 4(7), e6322. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006322

- Elman, I., Lukas, S. E., Karlsgodt, K. H., Gasic, G. P., & Breiter, H. C. (2003). Acute cortisol administration triggers craving in individuals with cocaine dependence. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28(1), 17-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(02)00016-0

- Anderson, K. E., Rosner, W., Khan, M. S., New, M. I., Pang, S. Y., Wissel, P. S., & Kappas, A. (1987). Diet-hormone interactions: protein/carbohydrate ratio alters reciprocally the plasma levels of testosterone and cortisol and their respective binding globulins in man. Life Sciences, 40(18), 1761-1768. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3205(87)90086-5

- Henderson, B. E., Ross, R., & Bernstein, L. (1988). Estrogens as a cause of human cancer: the Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Foundation award lecture. Cancer Research, 48(2), 246-253.

- Key, T., Appleby, P., Barnes, I., & Reeves, G. (2002). Endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of nine prospective studies. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 94(8), 606-616. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/94.8.606

- Schardein, J. L. (2000). Chemically induced birth defects (3rd ed.). Marcel Dekker.

- Siiteri, P. K., & Stites, D. P. (1982). Immunologic and endocrine interrelationships in pregnancy. Biology of Reproduction, 26(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod26.1.1

- Berlin, C. M., & Briggs, G. G. (2005). Drugs and chemicals in human milk. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 10(2), 149-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2004.09.011

- Hale, T. W. (2019). Hale’s medications & mothers’ milk 2019: A manual of lactational pharmacology (18th ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

- Tanaka, E. (1998). Clinically important pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions: role of cytochrome P450 enzymes. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 23(6), 403-416. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2710.1998.00086.x

- Dowling, T. C., Briglia, A. E., Fink, J. C., Hanes, D. S., Light, P. D., Stackiewicz, L., … & Inker, L. A. (2013). Characterization of hepatic cytochrome p4503A activity in patients with end-stage renal disease. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 94(3), 427-434. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2013.104

- Cushman, M., Kuller, L. H., Prentice, R., Rodabough, R. J., Psaty, B. M., Stafford, R. S., … & Rosendaal, F. R. (2004). Estrogen plus progestin and risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA, 292(13), 1573-1580. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.13.1573

- Scarabin, P. Y., Oger, E., & Plu-Bureau, G. (2003). Differential association of oral and transdermal oestrogen-replacement therapy with venous thromboembolism risk. The Lancet, 362(9382), 428-432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14066-4

- Zhou, S. F. (2008). Drugs behave as substrates, inhibitors and inducers of human cytochrome P450 3A4. Current Drug Metabolism, 9(4), 310-322. https://doi.org/10.2174/138920008784220664

- Lynch, T., & Price, A. (2007). The effect of cytochrome P450 metabolism on drug response, interactions, and adverse effects. American Family Physician, 76(3), 391-396.

- Guengerich, F. P. (1999). Cytochrome P-450 3A4: regulation and role in drug metabolism. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 39(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.1

- Dresser, G. K., Spence, J. D., & Bailey, D. G. (2000). Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic consequences and clinical relevance of cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 38(1), 41-57. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200038010-00003

- Moore, L. B., Goodwin, B., Jones, S. A., Wisely, G. B., Serabjit-Singh, C. J., Willson, T. M., … & Kliewer, S. A. (2000). St. John’s wort induces hepatic drug metabolism through activation of the pregnane X receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(13), 7500-7502. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.130155097

- Burger, H. G. (2002). Androgen production in women. Fertility and Sterility, 77(4), S3-S5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(02)02985-0

- Anttila, L., & Kunz, Y. (2000). Effects of oral contraceptives on markers of hyperandrogenism and SHBG in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Contraception, 62(5), 237-244. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-7824(00)00168-2

- Canonico, M., Plu-Bureau, G., Lowe, G. D., & Scarabin, P. Y. (2008). Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 336(7655), 1227-1231. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39555.441944.BE

- Hirsh, J., Fuster, V., Ansell, J., & Halperin, J. L. (2003). American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology foundation guide to warfarin therapy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 41(9), 1633-1652. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00416-9

- Reddy, D. S. (2009). The role of neurosteroids in the pathophysiology and treatment of catamenial epilepsy. Epilepsy Research, 85(1), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.02.017

- Zorumski, C. F., Paul, S. M., Izumi, Y., Covey, D. F., & Mennerick, S. (2013). Neurosteroids, stress and depression: potential therapeutic opportunities. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(1), 109-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.10.005

- Livingstone, C., & Collison, M. (2002). Sex steroids and insulin resistance. Clinical Science, 102(2), 151-166. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs1020151

- Miners, J. O., & Birkett, D. J. (1998). Cytochrome P4502C9: an enzyme of major importance in human drug metabolism. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 45(6), 525-538. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00721.x

- Prausnitz, M. R., Mitragotri, S., & Langer, R. (2004). Current status and future potential of transdermal drug delivery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 3(2), 115-124. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1304

- Guy, R. H., & Hadgraft, J. (1988). Pharmacokinetics of percutaneous absorption with concurrent metabolism. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 41(3), 183-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-5173(88)90016-1

- Zhai, H., & Maibach, H. I. (2004). Skin permeation enhancers: an overview. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology, 17(4), 143-152. https://doi.org/10.1159/000078824

- Basketter, D. A., Griffiths, H. A., Wang, X. M., Wilhelm, K. P., & McFadden, J. (2005). Individual, ethnic and seasonal variability in irritant susceptibility of skin: the implications for a predictive human patch test. Contact Dermatitis, 53(5), 285-289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00703.x

- Rupprecht, R. (2003). Neuroactive steroids: mechanisms of action and neuropsychopharmacological properties. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28(2), 139-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(02)00064-0

- Patchev, V. K., Hassan, A. H., Holsboer, D. F., & Almeida, O. F. (1996). The neurosteroid tetrahydroprogesterone attenuates the endocrine response to stress and exerts glucocorticoid-like effects on vasopressin gene transcription in the rat hypothalamus. Neuropsychopharmacology, 15(6), 533-540. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00096-6

- Dubrovsky, B. O. (2005). Steroids, neuroactive steroids and neurosteroids in psychopathology. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 29(2), 169-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.001

- Giangrande, P. H., & McDonnell, D. P. (1999). The A and B isoforms of the human progesterone receptor: two functionally different transcription factors encoded by a single gene. Recent Progress in Hormone Research, 54, 291-313.

- Krause, W., & Kühne, G. (1988). Pharmacokinetics of natural and synthetic gestagens after different administration routes. Contraception, 37(1), 69-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-7824(88)90063-6

- Rosano, G. M., Webb, C. M., Chierchia, S., Morgani, G. L., Gabraele, M., Sarrel, P. M., … & Collins, P. (2000). Natural progesterone, but not medroxyprogesterone acetate, enhances the beneficial effect of estrogen on exercise-induced myocardial ischemia in postmenopausal women. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 36(7), 2154-2159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00958-0

- Melcangi, R. C., Azcoitia, I., Ballabio, M., Cavarretta, I., Gonzalez, L. C., Leonelli, E., … & Garcia-Segura, L. M. (2003). Neuroactive steroids influence peripheral myelination: a promising opportunity for preventing or treating age-dependent dysfunctions of peripheral nerves. Progress in Neurobiology, 71(1), 57-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.09.003

- Lambert, J. J., Cooper, M. A., Simmons, R. D., Weir, C. J., & Belelli, D. (2009). Neurosteroids: endogenous allosteric modulators of GABA A receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(1), S48-S58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.009

- Morrow, A. L., Janis, G. C., VanDoren, M. J., Matthews, D. B., Samson, H. H., Janak, P. H., & Grant, K. A. (1999). Neurosteroids mediate pharmacological effects of ethanol: a new mechanism of ethanol action? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 23(12), 1933-1940. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04094.x

- Schardein, J. L., & Macina, O. T. (2007). Human developmental toxicants: aspects of toxicology and chemistry. CRC Press.

- Briggs, G. G., Freeman, R. K., & Yaffe, S. J. (2017). Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk (11th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Pasqualini, J. R. (2005). Enzymes involved in the formation and transformation of steroid hormones in the fetal and placental compartments. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 97(5), 401-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.08.004

- Pepe, G. J., & Albrecht, E. D. (1995). Actions of placental and fetal adrenal steroid hormones in primate pregnancy. Endocrine Reviews, 16(5), 608-648. https://doi.org/10.1210/edrv-16-5-608

- vom Saal, F. S., Timms, B. G., Montano, M. M., Palanza, P., Thayer, K. A., Nagel, S. C., … & Welshons, W. V. (1997). Prostate enlargement in mice due to fetal exposure to low doses of estradiol or diethylstilbestrol and opposite effects at high doses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 94(5), 2056-2061. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.5.2056

- Gray, L. E., Ostby, J., Furr, J., Wolf, C. J., Lambright, C., Parks, L., … & Guilette, L. J. (2001). Effects of environmental antiandrogens on reproductive development in experimental animals. Human Reproduction Update, 7(3), 248-264. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/7.3.248

- Conley, A., & Hinshelwood, M. (2001). Mammalian aromatases. Reproduction, 121(5), 685-695. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep.0.1210685

- Fowden, A. L., Li, J., & Forhead, A. J. (1998). Glucocorticoids and the preparation for life after birth: are there long-term consequences of the life insurance? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 57(1), 113-122. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS19980017

- Teratology Society. (2007). Teratology Society public affairs committee position paper: postmarketing surveillance of teratogens. Teratology, 75(5), 349-350. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.20397

- Chambers, C. D., & Jones, K. L. (2009). Teratology update: gestational effects of maternal hyperthermia due to febrile illnesses and resultant patterns of defects in humans. Teratology, 58(5), 209-221. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199811)58:5<209::AID-TERA8>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Czeizel, A. E., & Banhidy, F. (2011). Vitamin supply in pregnancy for the prevention of congenital birth defects. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 14(3), 291-296. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e328345993c

- Organization of Teratology Information Specialists. (2018). MotherToBaby fact sheets. Retrieved from https://mothertobaby.org/fact-sheets/

- Physicians’ Desk Reference. (2021). PDR for prescription drugs (75th ed.). PDR Network.

- International Conference on Harmonisation. (1998). ICH harmonised tripartite guideline: dose-response information to support drug registration E4. Federal Register, 63(46), 11466-11470.

- Bhargava, H. N., & Leonard, P. A. (1996). Triclosan: applications and safety. American Journal of Infection Control, 24(3), 209-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-6553(96)90017-6

- Guidance for Industry. (2003). Bioavailability and bioequivalence studies for orally administered drug products - general considerations. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

- Barry, B. W. (2001). Novel mechanisms and devices to enable successful transdermal drug delivery. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 14(2), 101-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0928-0987(01)00167-1

- Walters, K. A., & Roberts, M. S. (2002). The structure and function of skin. In K. A. Walters (Ed.), Dermatological and transdermal formulations (pp. 1-39). Marcel Dekker.

- Turek, F. W., & Gillette, M. U. (2004). Melatonin, sleep, and circadian rhythms: rationale for development of specific melatonin agonists. Sleep Medicine, 5(6), 523-532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2004.07.009

- Refinetti, R. (2006). Circadian physiology (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

- World Health Organization. (2003). Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization.

- Osterberg, L., & Blaschke, T. (2005). Adherence to medication. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(5), 487-497. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra050100

- Levy, G. (1998). Predicting effective drug concentrations for individual patients. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 34(4), 323-333. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199834040-00005

- Evans, W. E., & McLeod, H. L. (2003). Pharmacogenomics-drug disposition, drug targets, and side effects. New England Journal of Medicine, 348(6), 538-549. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra020526

- Carstensen, J. T., & Rhodes, C. T. (2000). Drug stability: principles and practices (3rd ed.). Marcel Dekker.

- Connors, K. A., Amidon, G. L., & Stella, V. J. (1986). Chemical stability of pharmaceuticals: a handbook for pharmacists (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Tonnesen, H. H. (2004). Photostability of drugs and drug formulations (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

- Moore, D. E. (2004). Drug-induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Safety, 25(5), 345-372. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200225050-00004

- Ahlneck, C., & Zografi, G. (1990). The molecular basis of moisture effects on the physical and chemical stability of drugs in the solid state. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 62(2-3), 87-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-5173(90)90221-O

- United States Pharmacopeia. (2019). General chapter <1191> stability considerations in dispensing practice. In USP 42-NF 37. United States Pharmacopeial Convention.

- Budnitz, D. S., Salis, S., Meldrum, S., Jones, A. L., & Button, J. (2005). Self-reported poison exposures in young children: a population-based study. Clinical Pediatrics, 44(4), 279-286. https://doi.org/10.1177/000992280504400402

- Rodgers, G. B. (2002). The effectiveness of child-resistant packaging for aspirin. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 156(9), 929-933. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.156.9.929

- United States Pharmacopeia. (2019). General chapter <1072> disinfectants and antiseptics. In USP 42-NF 37. United States Pharmacopeial Convention.

- Kohn, L. T., Corrigan, J. M., & Donaldson, M. S. (Eds.). (2000). To err is human: building a safer health system. National Academy Press.

- Bound, J. P., & Voulvoulis, N. (2005). Household disposal of pharmaceuticals as a pathway for aquatic contamination in the United Kingdom. Environmental Health Perspectives, 113(12), 1705-1711. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.8315

- Glassmeyer, S. T., Hinchey, E. K., Boehme, S. E., Daughton, C. G., Ruhoy, I. S., Conerly, O., … & Thompson, T. A. (2009). Disposal practices for unwanted residential medications in the United States. Environment International, 35(3), 566-572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2008.10.007

- World Health Organization. (2003). Temperature mapping of storage areas: guidance for temperature mapping studies. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 908, 75-88.

- International Air Transport Association. (2020). Dangerous goods regulations (61st ed.). IATA.

- Majewska, M. D., Harrison, N. L., Schwartz, R. D., Barker, J. L., & Paul, S. M. (1986). Steroid hormone metabolites are barbiturate-like modulators of the GABA receptor. Science, 232(4753), 1004-1007. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2422758

- Baulieu, E. E., & Robel, P. (1998). Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) as neuroactive neurosteroids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95(8), 4089-4091. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.8.4089

- Rupprecht, R., & Holsboer, F. (1999). Neuroactive steroids: mechanisms of action and neuropsychopharmacological perspectives. Trends in Neurosciences, 22(9), 410-416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01399-5

- Mellon, S. H., & Griffin, L. D. (2002). Neurosteroids: biochemistry and clinical significance. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 13(1), 35-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1043-2760(01)00503-3

- Mayo, W., George, O., Darbra, S., Bouyer, J. J., Vallée, M., Darnaudéry, M., … & Le Moal, M. (2003). Individual differences in cognitive aging: implication of pregnenolone sulfate. Progress in Neurobiology, 71(1), 43-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.09.006

- Steiger, A. (2002). Sleep and the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical system. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 6(2), 125-138. https://doi.org/10.1053/smrv.2001.0159

- Freeman, E. W., Sammel, M. D., Lin, H., & Nelson, D. B. (2006). Associations of hormones and menopausal status with depressed mood in women with no history of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(4), 375-382. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.375

- Vallée, M., Purdy, R. H., Vitiello, M. V., & Mayo, W. (2001). Pregnenolone, stress, and sleep. Brain Research Reviews, 37(1-3), 301-312. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00135-7

- Gould, E., Woolley, C. S., Frankfurt, M., & McEwen, B. S. (1990). Gonadal steroids regulate dendritic spine density in hippocampal pyramidal cells in adulthood. Journal of Neuroscience, 10(4), 1286-1291. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01286.1990

- Zhai, H., & Maibach, H. I. (2005). Skin permeation enhancers: an overview. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology, 18(4), 143-152. https://doi.org/10.1159/000086032

- Basketter, D. A., York, M., McFadden, J. P., & Robinson, M. K. (2004). Determination of skin irritation potential in the human 4-h patch test. Contact Dermatitis, 51(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0105-1873.2004.00345.x

- Cross, S. E., Anderson, C., Thompson, M. J., & Roberts, M. S. (2001). Is there tissue penetration after topical application of salicylic acid formulations? European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 12(3), 309-316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0928-0987(00)00174-2

- Walters, K. A. (2002). Penetration enhancers and their use in transdermal therapeutic systems. In K. A. Walters (Ed.), Dermatological and transdermal formulations (pp. 197-246). Marcel Dekker.

- Harrison, J. E., Watkinson, A. C., Green, D. M., Hadgraft, J., & Brain, K. (1996). The relative effect of Azone and Transcutol on permeant diffusivity and solubility in human stratum corneum. Pharmaceutical Research, 13(4), 542-546. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016036000396

- Moore, D. E. (2002). Drug-induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Safety, 25(5), 345-372. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200225050-00004

- Basketter, D. A., & Scholes, E. W. (1992). Comparison of the local lymph node assay with the guinea-pig maximization test for the detection of a range of contact allergens. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 30(1), 65-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-6915(92)90139-B

- Stanczyk, F. Z., Hapgood, J. P., Winer, S., & Mishell Jr, D. R. (2013). Progestogens used in postmenopausal hormone therapy: differences in their pharmacological properties, intracellular actions, and clinical effects. Endocrine Reviews, 34(2), 171-208. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2012-1008

- Wierman, M. E., Basson, R., Davis, S. R., Khosla, S., Miller, K. K., Rosner, W., & Santoro, N. (2006). Androgen therapy in women: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 91(10), 3697-3710. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-1121

- Somboonporn, W., & Davis, S. R. (2004). Testosterone effects on the breast: implications for testosterone therapy for women. Endocrine Reviews, 25(3), 374-388. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2003-0016

- Davis, S. R., Moreau, M., Kroll, R., Bouchard, C., Panay, N., Gass, M., … & APHRODITE Study Team. (2008). Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(19), 2005-2017. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0707302

- Rosner, W., Auchus, R. J., Azziz, R., Sluss, P. M., & Raff, H. (2007). Position statement: utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring testosterone: an Endocrine Society position statement. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 92(2), 405-413. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-1864

- Burger, H. G., Dudley, E. C., Cui, J., Dennerstein, L., & Hopper, J. L. (2000). A prospective longitudinal study of serum testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and sex hormone-binding globulin levels through the menopause transition. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 85(8), 2832-2838. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.85.8.6740

- Shifren, J. L., Braunstein, G. D., Simon, J. A., Casson, P. R., Buster, J. E., Redmond, G. P., … & Mazer, N. A. (2000). Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. New England Journal of Medicine, 343(10), 682-688. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200009073431002

- Osterberg, L., & Blaschke, T. (2005). Adherence to medication. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(5), 487-497. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra050100

- Hughes, D. A., Bagust, A., Haycox, A., & Walley, T. (2001). The impact of non-compliance on the cost-effectiveness of pharmaceuticals: a review of the literature. Health Economics, 10(7), 601-615. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.609

- Claxton, A. J., Cramer, J., & Pierce, C. (2001). A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clinical Therapeutics, 23(8), 1296-1310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2918(01)80109-0

- Cramer, J. A., Roy, A., Burrell, A., Fairchild, C. J., Fuldeore, M. J., Ollendorf, D. A., & Wong, P. K. (2008). Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value in Health, 11(1), 44-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x

- Haynes, R. B., Ackloo, E., Sahota, N., McDonald, H. P., & Yao, X. (2008). Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD000011. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3

- Simpson, S. H., Eurich, D. T., Majumdar, S. R., Padwal, R. S., Tsuyuki, R. T., Varney, J., & Johnson, J. A. (2006). A meta-analysis of the association between adherence to drug therapy and mortality. BMJ, 333(7557), 15. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38875.675486.55

- Penckofer, S., Kouba, J., Byrnes, M., & Estwing Ferrans, C. (2010). Vitamin D and depression: where is all the sunshine? Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31(6), 385-393. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840903437657

- Prasad, A. S. (2008). Zinc in human health: effect of zinc on immune cells. Molecular Medicine, 14(5-6), 353-357. https://doi.org/10.2119/2008-00033.Prasad

- Volpe, S. L. (2013). Magnesium in disease prevention and overall health. Advances in Nutrition, 4(3), 378S-383S. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.112.003483

- Emanuele, M. A., & Emanuele, N. V. (2001). Alcohol and the male reproductive system. Alcohol Research & Health, 25(4), 282-287.

- Hackney, A. C., & Lane, A. R. (2015). Exercise and the regulation of endocrine hormones. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, 135, 293-311. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.07.001

- McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873-904. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00041.2006

- Lovallo, W. R., Whitsett, T. L., al’Absi, M., Sung, B. H., Vincent, A. S., & Wilson, M. F. (2005). Caffeine stimulation of cortisol secretion across the waking hours in relation to caffeine intake levels. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67(5), 734-739. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000181270.20036.06

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E., Bourguignon, J. P., Giudice, L. C., Hauser, R., Prins, G. S., Soto, A. M., … & Gore, A. C. (2009). Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocrine Reviews, 30(4), 293-342. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2009-0002

- Guidance for Industry. (2003). INDs for phase 2 and phase 3 studies chemistry, manufacturing, and controls information. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

- United States Pharmacopeia. (2019). General chapter <7> labeling. In USP 42-NF 37. United States Pharmacopeial Convention.

- World Health Organization. (2003). Stability testing of active pharmaceutical ingredients and finished pharmaceutical products. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 953, Annex 2.

- Transportation Security Administration. (2020). What can I bring? TSA liquid rule. U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

- International Civil Aviation Organization. (2018). Technical instructions for the safe transport of dangerous goods by air. ICAO.

- World Health Organization. (2005). WHO good storage and distribution practices for medical products. In WHO Expert Committee on Specifications for Pharmaceutical Preparations: thirty-ninth report (pp. 204-252). World Health Organization.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2008). Guidance on the interdisciplinary safe use of automated dispensing cabinets. ISMP.

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection. (2019). Bringing medication into the U.S. for personal use. U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

- Reid, K. J., & Zee, P. C. (2009). Circadian rhythm disorders. Seminars in Neurology, 29(4), 393-405. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1237120

- Haynes, R. B., Taylor, D. W., & Sackett, D. L. (Eds.). (1979). Compliance in health care. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Farmer, K. C. (1999). Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clinical Therapeutics, 21(6), 1074-1090. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2918(99)80026-5

- Doherty, W. J., & Baird, M. A. (1983). Family therapy and family medicine: toward the primary care of families. Guilford Press.

- Vermeire, E., Hearnshaw, H., Van Royen, P., & Denekens, J. (2001). Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 26(5), 331-348. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00363.x

- Garnett, W. R. (2000). Clinical pharmacology of topiramate: a review. Epilepsia, 41(s1), S61-S65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb06058.x

- Burke, L. E., Dunbar-Jacob, J., & Hill, M. N. (1997). Compliance with cardiovascular disease prevention strategies: a review of the research. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 19(3), 239-263. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02892289

- Tachon, P. (1994). The problem of tolerance in the long-term treatment of insomnia with benzodiazepines. Acta Psychiatrica Belgica, 94(4), 270-277.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2009). Medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. NICE Clinical Guideline 76.

- Bushra, R., Aslam, N., & Khan, A. Y. (2011). Food-drug interactions. Oman Medical Journal, 26(2), 77-83. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2011.21

- Henderson, L., Yue, Q. Y., Bergquist, C., Gerden, B., & Arlett, P. (2002). St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): drug interactions and clinical outcomes. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 54(4), 349-356. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01683.x

- Zhdanova, I. V., Lynch, H. J., & Wurtman, R. J. (1997). Melatonin: a sleep-promoting hormone. Sleep, 20(10), 899-907. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/20.10.899

- Labrie, F., Luu-The, V., Bélanger, A., Lin, S. X., Simard, J., Pelletier, G., & Labrie, C. (2005). Is dehydroepiandrosterone a hormone? Journal of Endocrinology, 187(2), 169-196. https://doi.org/10.1677/joe.1.06264

- Miners, J. O., & Birkett, D. J. (1998). Cytochrome P4502C9: an enzyme of major importance in human drug metabolism. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 45(6), 525-538. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00721.x

- Low Dog, T. (2005). Menopause: a review of botanical dietary supplements. American Journal of Medicine, 118(12), 98-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.044

- Fleet, J. C. (2008). Molecular actions of vitamin D contributing to cancer prevention. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 29(6), 388-396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2008.07.003

- Wiechers, J. W., & Musee, N. (2010). Engineered inorganic nanoparticles and cosmetics: facts, issues, knowledge gaps and challenges. Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology, 6(5), 408-431. https://doi.org/10.1166/jbn.2010.1143

- Qato, D. M., Alexander, G. C., Conti, R. M., Johnson, M., Schumm, P., & Lindau, S. T. (2008). Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. JAMA, 300(24), 2867-2878. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2008.892

- Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press.

- Kohn, L. T., Corrigan, J. M., & Donaldson, M. S. (Eds.). (2000). To err is human: building a safer health system. National Academy Press.

- Wagner, E. H., Austin, B. T., Davis, C., Hindmarsh, M., Schaefer, J., & Bonomi, A. (2001). Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Affairs, 20(6), 64-78. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64

- Vermeulen, A., Verdonck, L., & Kaufman, J. M. (1999). A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 84(10), 3666-3672. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.84.10.6079

- Pratt, D. S., & Kaplan, M. M. (2000). Evaluation of abnormal liver-enzyme results in asymptomatic patients. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(17), 1266-1271. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200004273421707

- Chobanian, A. V., Bakris, G. L., Black, H. R., Cushman, W. C., Green, L. A., Izzo Jr, J. L., … & Roccella, E. J. (2003). Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension, 42(6), 1206-1252. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2

- Guyatt, G. H., Feeny, D. H., & Patrick, D. L. (1993). Measuring health-related quality of life. Annals of Internal Medicine, 118(8), 622-629. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092-1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Harlow, S. D., Gass, M., Hall, J. E., Lobo, R., Maki, P., Rebar, R. W., … & de Villiers, T. J. (2012). Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 97(4), 1159-1168. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-3362

- Stewart, A. L., & Ware Jr, J. E. (Eds.). (1992). Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Duke University Press.

- Sackett, D. L., Rosenberg, W. M., Gray, J. M., Haynes, R. B., & Richardson, W. S. (1996). Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ, 312(7023), 71-72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

What is pregnenolone cream and how does it work in the body?

Pregnenolone cream is a compounded topical medication containing pregnenolone, a naturally occurring steroid hormone precursor that serves as the starting material for the synthesis of various other steroid hormones in the body.[99] Often referred to as the “mother hormone,” pregnenolone is synthesized from cholesterol in various tissues, including the adrenal glands, brain, and reproductive organs.[100] When applied topically, the cream allows for localized delivery of pregnenolone through the skin, where it can be absorbed into the systemic circulation and converted to other active hormones as needed by the body. The compound works through multiple mechanisms, including direct interaction with neurotransmitter receptors, particularly GABA and NMDA receptors, and through its conversion to downstream hormones such as progesterone, DHEA, and cortisol.[101] This dual mechanism of action allows pregnenolone to potentially influence various physiological processes, including mood regulation, cognitive function, stress response, and hormonal balance.[102]

How long does it typically take to see results from pregnenolone cream?

The timeline for experiencing therapeutic effects from pregnenolone cream varies significantly among individuals and depends on multiple factors, including the specific indication being treated, baseline hormone levels, individual metabolism, and concurrent health conditions.[103] Some patients may notice initial effects within days to weeks of starting treatment, particularly for symptoms related to mood or energy levels, while other benefits may require several months of consistent use to become apparent.[104] For hormonal balance restoration, measurable changes in laboratory values may take 4-8 weeks to develop, while clinical symptom improvement may follow a different timeline.[105] Cognitive benefits, when they occur, may be among the first effects noticed, sometimes within the first few weeks of treatment.[106] However, patients should be advised that individual responses vary widely, and some individuals may require dose adjustments or extended treatment periods to achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes. Healthcare providers typically recommend a trial period of at least 3-6 months to adequately assess treatment response before making decisions about continuation or discontinuation.[107]

Are there any specific skin care considerations when using pregnenolone cream?

Proper skin care practices are important when using pregnenolone cream to optimize absorption, minimize local adverse effects, and maintain skin health throughout treatment.[108] The application site should be clean and dry before cream application, and patients should avoid applying the medication to broken, irritated, or inflamed skin areas.[109] Rotation of application sites is recommended to prevent local irritation and ensure consistent absorption patterns.[110] Gentle cleansing with mild, unscented soap before application can help remove barriers to absorption while minimizing skin irritation.[111] Patients should avoid applying other topical products, including moisturizers, sunscreens, or cosmetics, to the same area for at least 30 minutes after pregnenolone cream application to prevent interference with absorption.[112] Sun protection is important, as steroid hormones may potentially increase photosensitivity in some individuals.[113] If local skin reactions develop, such as redness, itching, or irritation, patients should consult their healthcare provider for guidance on whether to continue treatment or modify the application technique.[114]

Can pregnenolone cream be used alongside other hormone replacement therapies?

The concurrent use of pregnenolone cream with other hormone replacement therapies requires careful consideration and professional medical supervision due to the potential for complex interactions and additive effects.[115] Pregnenolone can be converted to various other steroid hormones in the body, including progesterone, estrogens, and androgens, which may enhance or interfere with existing hormone therapy regimens.[116] Patients currently receiving estrogen replacement therapy, progesterone supplementation, testosterone therapy, or thyroid hormone replacement should inform their healthcare provider before starting pregnenolone cream.[117] The combination may require adjustment of existing hormone dosages to maintain optimal hormonal balance and prevent adverse effects related to hormone excess.[118] Regular monitoring through laboratory testing may be necessary to assess hormone levels and ensure that the combined therapy remains within therapeutic ranges.[119] Healthcare providers may need to implement a staged approach to hormone therapy integration, starting with lower doses and gradually adjusting based on patient response and laboratory monitoring results.[120] The timing of different hormone applications may also need to be coordinated to optimize therapeutic outcomes.[121]

What should I do if I miss a dose of pregnenolone cream?

If a dose of pregnenolone cream is missed, patients should apply the missed dose as soon as they remember, unless it is almost time for the next scheduled application.[122] In cases where the next dose is due within a few hours, patients should skip the missed dose and resume the regular dosing schedule rather than applying double amounts.[123] Doubling doses to make up for missed applications is not recommended, as this may increase the risk of adverse effects and disrupt the steady-state hormone levels that treatment aims to achieve.[124] For patients on twice-daily dosing schedules, missing one application occasionally is unlikely to significantly impact therapeutic outcomes, but consistent adherence to the prescribed regimen is important for optimal results.[125] If doses are missed frequently, patients should discuss strategies for improving adherence with their healthcare provider, such as setting reminders, adjusting application timing to fit their daily routine, or addressing any concerns about side effects that might be affecting compliance.[126] Patients should not attempt to compensate for multiple missed doses by applying larger amounts or more frequent applications without consulting their healthcare provider.[127]

Are there any dietary or lifestyle modifications recommended while using pregnenolone cream?

While using pregnenolone cream, certain dietary and lifestyle modifications may help optimize therapeutic outcomes and support overall hormonal health.[128] A balanced diet rich in nutrients that support steroid hormone synthesis, including adequate protein, healthy fats, and essential vitamins and minerals, may enhance the body’s ability to utilize pregnenolone effectively.[129] Specific nutrients of importance include vitamin D, zinc, magnesium, and B-complex vitamins, which play roles in hormone metabolism and steroid synthesis pathways.[130] Patients should consider limiting alcohol consumption, as excessive alcohol intake can interfere with steroid hormone metabolism and liver function.[131] Regular exercise may help optimize hormone utilization and support overall endocrine function, though intense training should be balanced to avoid excessive stress on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.[132] Stress management techniques, including adequate sleep, relaxation practices, and stress reduction strategies, are particularly important since pregnenolone is involved in stress response pathways.[133] Caffeine intake should be monitored, as excessive consumption may interfere with sleep quality and stress hormone balance.[134] Patients should also be mindful of exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in personal care products, household items, and environmental sources that might interfere with hormone function.[135]

How should pregnenolone cream be stored during travel?

Traveling with pregnenolone cream requires special attention to storage conditions to maintain product stability and potency.[136] The medication should be kept in its original container with proper labeling to ensure identification and prevent confusion with other products.[137] Temperature control is crucial during travel, and the cream should not be left in vehicles where temperatures can reach extreme levels, particularly during hot weather.[138] For air travel, pregnenolone cream should be packed in carry-on luggage when possible to maintain better temperature control and prevent loss.[139] If checked baggage storage is necessary, the medication should be well-insulated and protected from temperature extremes.[140] Extended travel periods may require special arrangements for maintaining appropriate storage conditions, particularly in climates with extreme temperatures or high humidity.[141] Patients should carry a sufficient supply for the entire travel period plus additional amounts to account for potential delays or extended stays.[142] For international travel, patients should research destination country regulations regarding the importation of compounded medications and may need to carry prescribing physician documentation.[143] Time zone changes may require adjustment of application timing to maintain consistent dosing intervals.[144]

What are the signs that pregnenolone cream may not be working or may need dose adjustment?

Recognition of inadequate therapeutic response or the need for dose adjustment requires careful monitoring of both clinical symptoms and potential adverse effects.[145] Signs that the current dose may be insufficient include persistence of the original symptoms that prompted treatment initiation, lack of improvement in laboratory parameters after adequate treatment duration, or gradual return of symptoms after initial improvement.[146] Conversely, signs of excessive dosing may include the development of adverse effects such as mood changes, sleep disturbances, skin irritation at application sites, or symptoms suggestive of hormone excess.[147] Changes in menstrual patterns, unusual fatigue, persistent headaches, or significant mood alterations may indicate the need for dose modification.[148] Laboratory monitoring may reveal hormone levels outside the desired therapeutic range, prompting dose adjustments.[149] Patients should maintain a symptom diary to track both positive and negative changes during treatment, which can help healthcare providers make informed decisions about dose optimization.[150] The development of tolerance, where previously effective doses no longer provide therapeutic benefits, may also indicate the need for treatment reassessment.[151] Any concerning symptoms or lack of expected improvement should prompt consultation with the prescribing healthcare provider rather than patient-initiated dose modifications.[152]

Can pregnenolone cream cause interactions with over-the-counter medications or supplements?

Pregnenolone cream may interact with various over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements through multiple mechanisms, making it important for patients to inform their healthcare provider about all non-prescription products they use.[153] Supplements that affect hormone metabolism, such as St. John’s wort, may alter pregnenolone metabolism and effectiveness.[154] Melatonin supplements might interact with pregnenolone’s effects on sleep patterns and circadian rhythms.[155] DHEA supplements could potentially lead to additive effects, as pregnenolone can be converted to DHEA in the body.[156] Over-the-counter pain medications, particularly those affecting liver metabolism, may influence steroid hormone processing.[157] Herbal supplements with estrogenic or androgenic properties, such as black cohosh or saw palmetto, may interact with pregnenolone metabolites.[158] Vitamin and mineral supplements generally do not pose significant interaction risks, but high-dose vitamin D or calcium supplements may influence steroid hormone metabolism.[159] Topical products applied to the same skin areas, including over-the-counter creams, lotions, or pain relief products, may interfere with pregnenolone absorption.[160] Patients should provide their healthcare provider with a complete list of all over-the-counter products, including vitamins, minerals, herbal supplements, and topical medications, to ensure safe and effective treatment.[161]

What monitoring or follow-up is typically required while using pregnenolone cream?

Regular monitoring and follow-up are essential components of safe and effective pregnenolone cream therapy, with the specific monitoring schedule and parameters determined by individual patient factors and treatment goals.[162] Initial follow-up appointments are typically scheduled within 4-6 weeks of treatment initiation to assess early response, tolerability, and the need for dose adjustments.[163] Subsequent monitoring intervals may extend to every 3-6 months once stable therapeutic responses are achieved.[164] Laboratory monitoring may include assessment of relevant hormone levels, such as pregnenolone, progesterone, cortisol, DHEA-S, and sex hormones, depending on the indication for treatment.[165] Liver function tests may be periodically performed to ensure that steroid hormone metabolism is not adversely affecting hepatic function.[166] Blood pressure monitoring may be important for some patients, as steroid hormones can influence cardiovascular parameters.[167] Assessment of treatment response should include evaluation of the original symptoms or conditions that prompted therapy initiation.[168] Monitoring for adverse effects includes assessment of mood changes, sleep patterns, skin reactions at application sites, and any symptoms suggestive of hormonal imbalance.[169] Female patients may require monitoring of menstrual patterns and reproductive function.[170] Patient-reported outcome measures and quality of life assessments may help quantify treatment benefits and guide therapy optimization.[171] Healthcare providers should also periodically reassess the continued need for treatment and consider alternative therapeutic approaches if response is inadequate.[172]

Disclaimer: This compounded medication is prepared under section 503A of the U.S. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Safety and efficacy for this formulation have not been evaluated by the FDA. Therapy should be initiated and monitored only by qualified healthcare professionals.

Administration Instructions

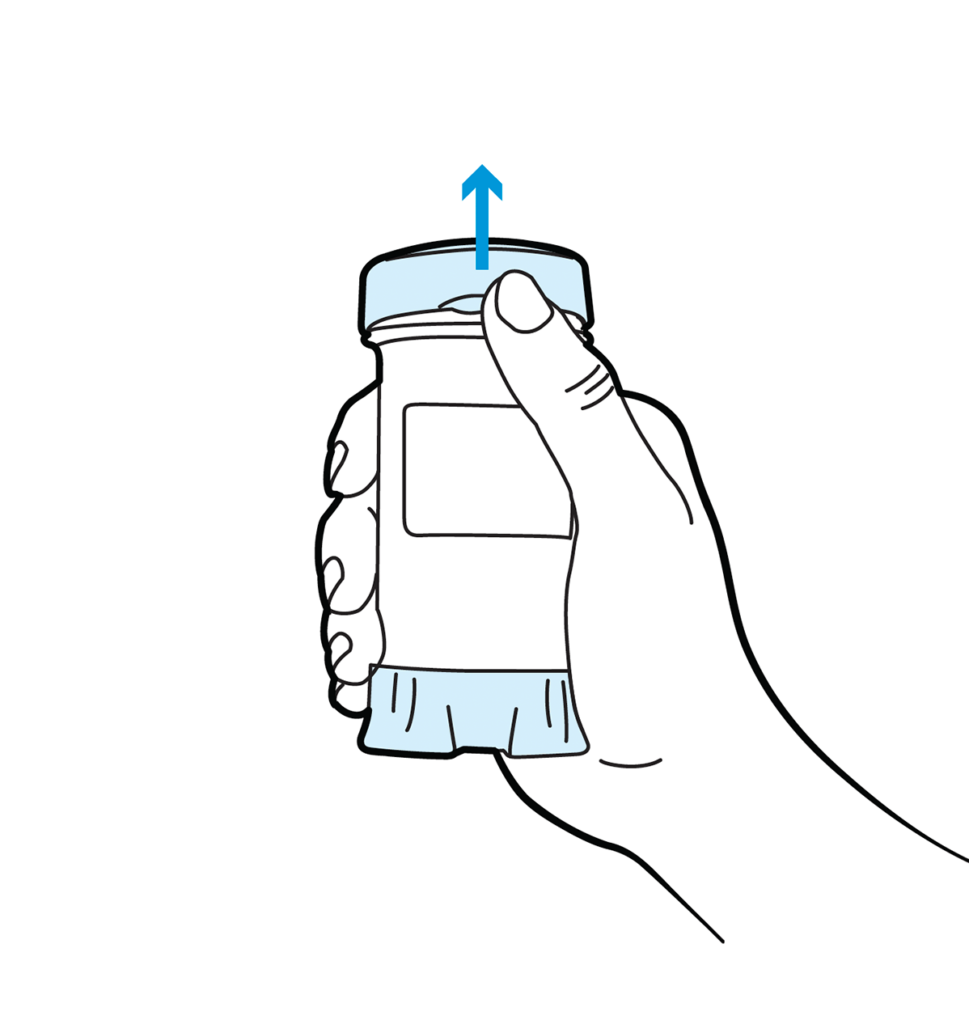

Topi-Click Dispensing Instructions

503A vs 503B

- 503A pharmacies compound products for specific patients whose prescriptions are sent by their healthcare provider.

- 503B outsourcing facilities compound products on a larger scale (bulk amounts) for healthcare providers to have on hand and administer to patients in their offices.

Frequently asked questions

Our team of experts has the answers you're looking for.

A clinical pharmacist cannot recommend a specific doctor. Because we are licensed in all 50 states*, we can accept prescriptions from many licensed prescribers if the prescription is written within their scope of practice and with a valid patient-practitioner relationship.

*Licensing is subject to change.

Each injectable IV product will have the osmolarity listed on the label located on the vial.

Given the vastness and uniqueness of individualized compounded formulations, it is impossible to list every potential compound we offer. To inquire if we currently carry or can compound your prescription, please fill out the form located on our Contact page or call us at (877) 562-8577.

We source all our medications and active pharmaceutical ingredients from FDA-registered suppliers and manufacturers.

DHEA / Pregnenolone Capsules

DHEA / Pregnenolone Capsules DHEA Cream

DHEA Cream Estradiol Cream

Estradiol Cream Estradiol Cypionate Injection

Estradiol Cypionate Injection Progesterone Capsules

Progesterone Capsules Progesterone Cream

Progesterone Cream Testosterone Cream

Testosterone Cream DHEA Capsules

DHEA Capsules Bi-Est Cream

Bi-Est Cream