Product Overview

† commercial product

Lisinopril tablets represent a widely utilized class of antihypertensive medication belonging to the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor family. This pharmaceutical preparation may be prescribed for the management of various cardiovascular conditions, including hypertension, heart failure, and myocardial infarction recovery.[1] The medication functions through inhibition of the angiotensin-converting enzyme, which could potentially result in vasodilation and reduced blood pressure in appropriate patient populations.[2]

Lisinopril demonstrates potential efficacy in both monotherapy and combination therapy regimens for blood pressure management. Healthcare providers may consider this medication for patients requiring long-term cardiovascular risk reduction strategies.[3] The formulation is available in multiple dosage strengths to accommodate individual patient needs and titration requirements during treatment optimization.[4]

Clinical studies have suggested that lisinopril may provide beneficial effects in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality when used as part of comprehensive treatment approaches. The medication’s pharmacokinetic profile allows for once-daily dosing in most patient populations, which could potentially enhance medication adherence.[5] Prescribing healthcare professionals should carefully evaluate individual patient characteristics, comorbidities, and concurrent medications before initiating therapy.[6]

The therapeutic applications of lisinopril extend beyond primary hypertension management, as research has indicated potential benefits in diabetic nephropathy prevention and heart failure treatment. Patients with left ventricular dysfunction following myocardial infarction may experience improved outcomes when lisinopril is incorporated into their treatment regimen.[7] Long-term studies have demonstrated that ACE inhibitor therapy, including lisinopril, could contribute to cardiovascular protection in high-risk patient populations.[8]

Lisinopril tablets are typically administered orally once daily, with or without food, as absorption is not significantly affected by meal timing. The initial dosage should be individualized based on patient characteristics, indication, and concurrent medications.[57] For hypertension management, the usual starting dose ranges from 5 to 10 mg once daily, with titration based on blood pressure response.[58]

Patients not receiving diuretic therapy may begin with 10 mg once daily, while those currently taking diuretics should start with a lower dose of 2.5 to 5 mg to minimize the risk of excessive hypotension.[59] Dose titration should occur gradually, typically at intervals of 2 to 4 weeks, to allow for adequate assessment of therapeutic response.[60]

The maximum recommended daily dose for most indications is 40 mg, although some patients may require higher doses under careful medical supervision. Elderly patients or those with renal impairment may require dose reduction or extended dosing intervals.[61] Creatinine clearance should be considered when determining appropriate dosing strategies for patients with kidney dysfunction.[62]

For heart failure management, lisinopril therapy typically begins with 2.5 to 5 mg once daily, with gradual titration to the maximum tolerated dose. Target doses for heart failure patients often range from 20 to 40 mg daily, depending on patient tolerance and clinical response.[63] Blood pressure and renal function should be monitored closely during dose escalation.[64]

Patients who miss a dose should take it as soon as remembered, unless it is close to the time for the next scheduled dose. Double dosing should be avoided to prevent excessive hypotension.[65] Consistency in timing of daily administration may help optimize therapeutic outcomes and improve patient adherence.[66]

Lisinopril exerts its therapeutic effects through competitive inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme, a critical component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. This enzyme normally catalyzes the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor that may contribute to elevated blood pressure and cardiovascular stress.[9] By blocking this conversion process, lisinopril could potentially reduce circulating levels of angiotensin II, leading to decreased peripheral vascular resistance.[10]

The inhibition of ACE may also result in reduced aldosterone secretion from the adrenal cortex, which could potentially lead to decreased sodium and water retention. This mechanism may contribute to the overall antihypertensive effects observed with lisinopril therapy.[11] Additionally, ACE inhibition might prevent the degradation of bradykinin, a vasodilatory peptide that could enhance the medication’s blood pressure-lowering effects.[12]

Lisinopril’s molecular structure allows for high specificity binding to the ACE enzyme active site, potentially resulting in prolonged inhibition compared to some other ACE inhibitors. The medication does not require hepatic metabolism for activation, as it is administered in its active form, which may provide more predictable pharmacokinetic profiles across diverse patient populations.[13] This characteristic could be particularly relevant for patients with hepatic impairment or those taking medications that affect liver enzyme activity.[14]

The cardiovascular protective effects of lisinopril may extend beyond blood pressure reduction through several proposed mechanisms. These could include improvement in endothelial function, reduction in oxidative stress, and potential antiatherosclerotic effects.[15] Some research has suggested that ACE inhibitors like lisinopril might influence cardiac remodeling processes, particularly in patients with heart failure or following myocardial infarction.[16]

Lisinopril therapy is contraindicated in patients with documented hypersensitivity to lisinopril, other ACE inhibitors, or any component of the formulation. Previous episodes of angioedema associated with ACE inhibitor use represent an absolute contraindication due to the potential for life-threatening reactions.[17] Healthcare providers should carefully screen patients for any history of angioedema before initiating lisinopril therapy.[18]

Pregnancy represents another significant contraindication for lisinopril use, particularly during the second and third trimesters. The medication may cause fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality when administered to pregnant women.[19] Women of childbearing potential should be counseled about pregnancy risks and appropriate contraceptive measures before starting lisinopril therapy.[20]

Concurrent use of lisinopril with aliskiren is contraindicated in patients with diabetes mellitus due to increased risks of hyperkalemia, hypotension, and renal dysfunction. This combination has been associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes in clinical trials.[21] Similarly, the combination of lisinopril with aliskiren should be avoided in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment.[22]

Patients with bilateral renal artery stenosis or stenosis of a solitary functioning kidney may experience acute renal failure when treated with ACE inhibitors like lisinopril. This condition represents a relative contraindication that requires careful evaluation of risk-benefit ratios.[23] Healthcare providers should assess renal function and consider alternative treatment options in patients with known or suspected renovascular disease.[24]

Lisinopril may interact with various medications, potentially altering their efficacy or increasing the risk of adverse effects. Potassium-sparing diuretics, potassium supplements, and salt substitutes containing potassium could potentially increase serum potassium levels when used concurrently with lisinopril.[25] Regular monitoring of electrolyte levels may be warranted in patients receiving these combinations.[26]

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may reduce the antihypertensive effects of lisinopril and could potentially increase the risk of renal dysfunction, particularly in elderly patients or those with compromised kidney function. The combination may also increase the risk of hyperkalemia.[27] Healthcare providers should consider alternative pain management strategies or closely monitor renal function when concurrent use is necessary.[28]

Lithium concentrations may be increased when used concurrently with lisinopril, potentially leading to lithium toxicity. The mechanism likely involves reduced renal lithium clearance due to ACE inhibitor effects on kidney function.[29] Patients receiving both medications may require more frequent lithium level monitoring and possible dose adjustments.[30]

Diabetic patients receiving insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents may experience enhanced glucose-lowering effects when lisinopril is added to their regimen. This interaction could potentially result in hypoglycemia, particularly during the initial weeks of combination therapy.[31] Blood glucose monitoring may need to be intensified when initiating lisinopril in diabetic patients.[32]

Gold compounds used for rheumatoid arthritis treatment may interact with ACE inhibitors like lisinopril, potentially causing nitritoid reactions characterized by facial flushing, nausea, vomiting, and hypotension. Although rare, healthcare providers should be aware of this potential interaction.[33] The mechanism of this interaction remains incompletely understood but may involve altered prostaglandin metabolism.[34]

Lisinopril therapy may be associated with various adverse effects, ranging from mild to severe in intensity. The most commonly reported side effect is a persistent dry cough, which occurs in approximately 10-20% of patients receiving ACE inhibitor therapy.[35] This cough is typically nonproductive and may develop within days to months after initiating treatment.[36]

Hypotension, particularly orthostatic hypotension, may occur during lisinopril therapy, especially following the initial dose or during dose titration. This effect could be more pronounced in patients who are volume-depleted, elderly, or receiving concurrent diuretic therapy.[37] Patients should be advised to rise slowly from sitting or lying positions to minimize the risk of falls.[38]

Hyperkalemia represents a potentially serious adverse effect that may occur with lisinopril use, particularly in patients with renal impairment, diabetes mellitus, or those receiving potassium supplements. Regular monitoring of serum potassium levels is recommended, especially during treatment initiation and dose adjustments.[39] Severe hyperkalemia could potentially lead to cardiac arrhythmias and requires immediate medical attention.[40]

Renal function deterioration may occur in susceptible patients, particularly those with pre-existing kidney disease, bilateral renal artery stenosis, or severe heart failure. Increases in serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels should be monitored regularly.[41] Acute renal failure, although uncommon, has been reported with ACE inhibitor therapy.[42]

Angioedema is a rare but potentially life-threatening adverse effect that may occur at any time during lisinopril therapy. This condition typically involves swelling of the face, lips, tongue, throat, or extremities and requires immediate discontinuation of the medication.[43] African American patients may have a higher risk of developing angioedema compared to other ethnic groups.[44]

Additional adverse effects that have been reported with lisinopril include headache, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, and skin rash. These effects are generally mild to moderate in severity and may resolve with continued therapy.[45] Some patients may experience taste disturbances or decreased libido during treatment.[46]

Lisinopril use during pregnancy poses significant risks to both maternal and fetal health, particularly during the second and third trimesters. The medication crosses the placenta and may cause fetal and neonatal complications including oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth retardation, and premature delivery.[47] Fetal exposure to ACE inhibitors has been associated with hypotension, renal dysfunction, and skull hypoplasia.[48]

Women who become pregnant while taking lisinopril should discontinue the medication as soon as pregnancy is detected and consult with their healthcare provider for alternative treatment options. The risks associated with ACE inhibitor exposure appear to be greatest during the second and third trimesters when fetal kidney development occurs.[49] However, first-trimester exposure has also been associated with increased risk of birth defects in some studies.[50]

Neonates whose mothers received lisinopril during pregnancy may experience hypotension, oliguria, and hyperkalemia following birth. These infants may require intensive monitoring and supportive care, including exchange transfusion or dialysis in severe cases.[51] The half-life of lisinopril may be prolonged in neonates due to immature renal function.[52]

Women of childbearing potential should be counseled about pregnancy risks before initiating lisinopril therapy and advised to use effective contraception throughout treatment. Alternative antihypertensive medications that are considered safer during pregnancy, such as methyldopa or certain calcium channel blockers, should be considered for women planning pregnancy.[53] Regular pregnancy testing may be appropriate for sexually active women receiving lisinopril.[54]

Breastfeeding considerations require careful evaluation as lisinopril is excreted in breast milk, although in relatively small amounts. The effects on nursing infants are not well-established, and alternative medications may be preferred for lactating mothers.[55] Healthcare providers should weigh the benefits of breastfeeding against the potential risks of infant drug exposure.[56]

Lisinopril tablets should be stored at controlled room temperature, typically between 20°C to 25°C (68°F to 77°F), with brief excursions permitted between 15°C to 30°C (59°F to 86°F). The medication should be kept in its original container to protect from light and moisture.[67] Exposure to excessive heat, humidity, or direct sunlight may compromise tablet integrity and potency.[68]

The original packaging typically includes a desiccant to absorb moisture and should remain in the bottle to maintain product stability. Patients should be advised not to remove the desiccant packet and to keep the container tightly closed when not in use.[69] Bathroom storage should be avoided due to fluctuating temperature and humidity levels.[70]

Lisinopril tablets should be kept out of reach of children and pets to prevent accidental ingestion. The medication should not be transferred to pill organizers or other containers unless specifically recommended by the pharmacist.[71] Child-resistant packaging is typically provided to enhance safety.[72]

Expired or unused lisinopril tablets should be disposed of properly according to local guidelines or pharmacy take-back programs. Flushing medications down the toilet or throwing them in household trash should generally be avoided unless specifically recommended by disposal guidelines.[73] Many communities offer medication disposal events or permanent collection sites for safe pharmaceutical waste management.[74]

Healthcare facilities and pharmacies should follow appropriate storage and handling procedures to maintain product quality and prevent contamination. Temperature monitoring and inventory rotation practices help ensure that patients receive medications within their shelf-life specifications.[75] Staff should be trained on proper handling procedures to minimize exposure risks.[76]

- Pfeffer, M. A., Braunwald, E., Moyé, L. A., Basta, L., Brown Jr, E. J., Cuddy, T. E., … & Rutherford, J. (1992). Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine, 327(10), 669-677. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199209033271001

- Brown, N. J., & Vaughan, D. E. (1998). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Circulation, 97(14), 1411-1420. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.97.14.1411

- The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators. (2002). Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic. JAMA, 288(23), 2981-2997. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.23.2981

- Cushman, W. C., Ford, C. E., Cutler, J. A., Margolis, K. L., Davis, B. R., Grimm, R. H., … & Probstfield, J. L. (2002). Success and predictors of blood pressure control in diverse North American settings. Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 4(6), 393-404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.02045.x

- Waeber, B. (2001). Treatment strategy to control blood pressure optimally in hypertensive patients. Blood Pressure, 10(2), 62-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/080370501750307634

- Chobanian, A. V., Bakris, G. L., Black, H. R., Cushman, W. C., Green, L. A., Izzo Jr, J. L., … & Roccella, E. J. (2003). Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension, 42(6), 1206-1252. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2

- Garg, R., & Yusuf, S. (1995). Overview of randomized trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. JAMA, 273(18), 1450-1456. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03520420066040

- Yusuf, S., Sleight, P., Pogue, J., Bosch, J., Davies, R., & Dagenais, G. (2000). Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(3), 145-153. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200001203420301

- Griendling, K. K., & Murphy, T. J. (1994). Molecular biology of the renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension, 23(1), 18-34. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.23.1.18

- Dzau, V. J. (1993). Tissue renin-angiotensin system: physiologic and pharmacologic implications. Circulation, 77(6_Pt_2), I1-I13. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.77.6.I1

- Weber, M. A. (2001). Interrupting the renin-angiotensin system: the role of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists in the treatment of hypertension. American Journal of Hypertension, 14(11), 280S-286S. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-7061(01)02173-3

- Campbell, D. J. (2001). The kallikrein-kinin system in humans. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology, 28(12), 1060-1065. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03564.x

- Johnston, C. I. (1992). ACE inhibitors in perspective: the long and short of it. Drugs, 44(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199244010-00001

- Sica, D. A. (2007). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ACE inhibitors in end-stage renal disease. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease, 14(2), 176-188. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2007.01.008

- Hornig, B., Landmesser, U., Kohler, C., Ahlersmann, D., Spiekermann, S., Christoph, A., … & Drexler, H. (2001). Comparative effect of ACE inhibition and angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonism on bioavailability of nitric oxide in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation, 103(6), 799-805. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.103.6.799

- Pfeffer, M. A., & Braunwald, E. (1990). Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: experimental observations and clinical implications. Circulation, 81(4), 1161-1172. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.81.4.1161

- Cicardi, M., Zingale, L. C., Bergamaschini, L., & Agostoni, A. (2004). Angioedema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use: outcome after switching to a different treatment. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(8), 910-913. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.8.910

- Kostis, J. B., Kim, H. J., Rusnak, J., Casale, T., Kaplan, A., Corren, J., & Levy, E. (2005). Incidence and characteristics of angioedema associated with enalapril. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(14), 1637-1642. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.14.1637

- Cooper, W. O., Hernandez-Diaz, S., Arbogast, P. G., Dudley, J. A., Dyer, S., Gideon, P. S., … & Ray, W. A. (2006). Major congenital malformations after first-trimester exposure to ACE inhibitors. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(23), 2443-2451. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa055202

- Podymow, T., & August, P. (2008). Update on the use of antihypertensive drugs in pregnancy. Hypertension, 51(4), 960-969. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.075895

- Parving, H. H., Brenner, B. M., McMurray, J. J., de Zeeuw, D., Haffner, S. M., Solomon, S. D., … & Baroletti, S. (2012). Cardiorenal end points in a trial of aliskiren for type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(23), 2204-2213. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1208799

- Fried, L. F., Emanuele, N., Zhang, J. H., Brophy, M., Conner, T. A., Duckworth, W., … & Peduzzi, P. (2013). Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(20), 1892-1903. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1303154

- Textor, S. C., Novick, A. C., Tarazi, R. C., Klimas, V., Vidt, D. G., & Pohl, M. (1983). Critical perfusion pressure for renal function in patients with bilateral atherosclerotic renal vascular disease. Annals of Internal Medicine, 98(6), 938-946. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-98-6-938

- Olin, J. W., Piedmonte, M. R., Young, J. R., DeAnna, S., Grubb, M., & Childs, M. B. (1995). The utility of duplex ultrasound scanning of the renal arteries for diagnosing significant renal artery stenosis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 122(11), 833-838. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-122-11-199506010-00004

- Palmer, B. F. (2004). Managing hyperkalemia caused by inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(6), 585-592. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra035279

- Schepkens, H., Vanholder, R., Billiouw, J. M., & Lameire, N. (2001). Life-threatening hyperkalemia during combined therapy with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and spironolactone: an analysis of 25 cases. American Journal of Medicine, 110(6), 438-441. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00676-4

- Johnson, A. G., Nguyen, T. V., & Day, R. O. (1994). Do nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs affect blood pressure? A meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 121(4), 289-300. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-121-4-199408150-00011

- Radack, K. L., Deck, C. C., & Bloomfield, S. S. (1987). Ibuprofen interferes with the efficacy of antihypertensive drugs: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ibuprofen compared with acetaminophen. Annals of Internal Medicine, 107(5), 628-635. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-107-5-628

- Finley, P. R., Warner, M. D., & Peabody, C. A. (1995). Clinical relevance of drug interactions with lithium. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 29(3), 172-191. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199529030-00004

- Crabtree, B. L., Mack, J. E., Johnson, C. D., & Amyx, B. C. (1991). Comparison of the effects of hydrochlorothiazide and furosemide on lithium disposition. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148(9), 1060-1063. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.148.9.1060

- Herings, R. M., de Boer, A., Stricker, B. H. C., Leufkens, H. G., & Porsius, A. (1995). Hypoglycaemia associated with use of inhibitors of angiotensin converting enzyme. The Lancet, 345(8959), 1195-1198. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91991-9

- Moen, M. D., Wagstaff, A. J., & Keating, G. M. (2006). Lisinopril: a review of its use in hypertension. Drugs, 66(2), 215-229. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200666020-00007

- Healey, L. A., Backes, M. B., Mason, J., & Sewell, J. R. (1989). Complications of intravenous gold. Journal of Rheumatology, 16(7), 945-946.

- Gottlieb, S. S., McCarter, R. J., & Vogel, R. A. (1998). Effect of beta-blockade on mortality among high-risk and low-risk patients after myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine, 339(8), 489-497. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199808203390801

- Os, I., Bratland, B., Dahlöf, B., Gisholt, K., Syvertsen, J. O., & Tretli, S. (1992). Female preponderance for lisinopril-induced cough in hypertension. American Journal of Hypertension, 5(12), 1040-1042. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/5.12.1040

- Israili, Z. H., & Hall, W. D. (1992). Cough and angioneurotic edema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy: a review of the literature and pathophysiology. Annals of Internal Medicine, 117(3), 234-242. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-117-3-234

- Massie, B. M., Kramer, B. L., Topic, N., & Henderson, S. G. (1987). Hemodynamic and radionuclide effects of acute captopril therapy for heart failure: changes in left and right ventricular volumes and function at rest and during exercise. Circulation, 76(6), 1262-1273. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.76.6.1262

- Leipzig, R. M., Cumming, R. G., & Tinetti, M. E. (1999). Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: II. Cardiac and analgesic drugs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 47(1), 40-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01899.x

- Juurlink, D. N., Mamdani, M. M., Lee, D. S., Kopp, A., Austin, P. C., Laupacis, A., & Redelmeier, D. A. (2004). Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(6), 543-551. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa040135

- Einhorn, L. M., Zhan, M., Hsu, V. D., Walker, L. D., Moen, M. F., Seliger, S. L., … & Fink, J. C. (2009). The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169(12), 1156-1162. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.132

- Bakris, G. L., & Weir, M. R. (2000). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated elevations in serum creatinine: is this a cause for concern? Archives of Internal Medicine, 160(5), 685-693. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.5.685

- Schoolwerth, A. C., Sica, D. A., Ballermann, B. J., & Wilcox, C. S. (2001). Renal considerations in angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor therapy: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease and the Council for High Blood Pressure Research of the American Heart Association. Circulation, 104(16), 1985-1991. https://doi.org/10.1161/hc4101.096153

- Morimoto, T., Gandhi, T. K., Fiskio, J. M., Seger, A. C., So, J. W., Cook, E. F., … & Bates, D. W. (2004). An evaluation of risk factors for adverse drug events associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 10(4), 499-509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00484.x

- Brown, N. J., Ray, W. A., Snowden, M., & Griffin, M. R. (1996). Black Americans have an increased rate of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 60(1), 8-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90161-7

- Atwood, J. E., Borhani, N. O., Dunn, F. G., Gifford, R., Kilcoyne, M., Kirkendall, W. M., … & Weissfeld, J. (1991). Management of patients on chronic ACE inhibitor treatment: recommendations of a consensus panel. Clinical Cardiology, 14(6), 471-480. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.4960140605

- Grimm Jr, R. H., Grandits, G. A., Prineas, R. J., McDonald, R. H., Lewis, C. E., Flack, J. M., … & Stamler, J. (1997). Long-term effects on sexual function of five antihypertensive drugs and nutritional hygienic treatment in hypertensive men and women. Hypertension, 29(1), 8-14. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.29.1.8

- Shotan, A., Widerhorn, J., Hurst, A., & Elkayam, U. (1994). Risks of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition during pregnancy: experimental and clinical evidence, potential mechanisms, and recommendations for use. American Journal of Medicine, 96(5), 451-456. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(94)90172-4

- Pryde, P. G., Sedman, A. B., Nugent, C. E., & Barr Jr, M. (1993). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor fetopathy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 3(9), 1575-1582. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.V391575

- Mastrobattista, J. M., Skupski, D. W., Monga, M., Blanco, J. D., & August, P. (1997). The rate of severe oligohydramnios and associated decreased fetal renal function associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use in pregnancy. American Journal of Perinatology, 14(01), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-994088

- Li, D. K., Yang, C., Andrade, S., Tavares, V., & Ferber, J. R. (2011). Maternal exposure to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in the first trimester and risk of malformations in offspring: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ, 343, d5931. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5931

- Lip, G. Y., Churchill, D., Beevers, M., Auckett, A., & Beevers, D. G. (1997). Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors in early pregnancy. The Lancet, 350(9089), 1446-1447. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64068-8

- Beermann, B., Groschinsky-Grind, M., & Rosén, A. (1976). Absorption, metabolism, and excretion of hydrochlorothiazide. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 19(5), 531-537. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt1976195part1531

- Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. (2000). American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 183(1), S1-S22. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2000.107928

- Seely, E. W., & Ecker, J. (2014). Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Circulation, 129(11), 1254-1261. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003904

- Redman, C. W., Kelly, J. G., & Cooper, W. D. (1990). The excretion of enalapril and enalaprilat in human breast milk. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 38(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00314816

- Devlin, R. G., & Fleiss, P. M. (1981). Captopril in human blood and breast milk. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 21(2-3), 110-113. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02186.x

- Pool, J. L., Cushman, W. C., Saini, R. K., Nwachuku, C. E., & Battikha, J. P. (2007). Use of the factorial design and quadratic response surface models to evaluate the fosinopril and hydrochlorothiazide combination therapy in hypertension. American Journal of Hypertension, 20(1), 83-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.06.006

- Frohlich, E. D., Grimm Jr, R. H., Labarthe, D. R., Maxwell, M. H., Perloff, D., & Weidman, W. H. (1988). Recommendations for human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometers: report of a special task force appointed by the steering committee, American Heart Association. Circulation, 77(2), 501A-514A. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.77.2.501A

- MacFadyen, R. J., Reid, J. L., & Elliott, H. L. (1993). Enalapril clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 25(4), 274-282. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199325040-00003

- Morgan, T., Anderson, A., & Bertram, D. (2001). Effect of indomethacin on blood pressure in elderly people with essential hypertension well controlled on amlodipine or enalapril. American Journal of Hypertension, 14(11), 1112-1116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-7061(01)02208-8

- Sica, D. A. (2003). ACE inhibitor pharmacology and drug interactions of clinical significance. Congestive Heart Failure, 9(4), 185-193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-5299.2003.01450.x

- Chrysant, S. G., Chrysant, G. S., Dimas, B., Binnion, P., Archer, R., & Garofolo, L. (1993). Effects of lisinopril on blood pressure, heart rate, and exercise tolerance in patients with congestive heart failure. Clinical Therapeutics, 15(6), 1065-1076.

- Hunt, S. A., Abraham, W. T., Chin, M. H., Feldman, A. M., Francis, G. S., Ganiats, T. G., … & Yancy, C. W. (2009). 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 53(15), e1-e90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013

- Konstam, M. A., Rousseau, M. F., Kronenberg, M. W., Udelson, J. E., Melin, J., Stewart, D., … & Yusuf, S. (1992). Effects of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril on the long-term progression of left ventricular dysfunction in patients with heart failure. Circulation, 86(2), 431-438. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.86.2.431

- Bangalore, S., Kamalakkannan, G., Parkar, S., & Messerli, F. H. (2007). Fixed-dose combinations improve medication compliance: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Medicine, 120(8), 713-719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.08.033

- Bramley, T. J., Gerbino, P. P., Nightengale, B. S., & Frech-Tamas, F. (2006). Relationship of blood pressure control to adherence with antihypertensive monotherapy in 13 managed care organizations. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy, 12(3), 239-245. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.3.239

- Trissel, L. A. (2000). Stability of compounded formulations. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 57(18), 1666-1674. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/57.18.1666

- Loftsson, T., Gudmundsdóttir, H., Sigurjónsdóttir, J. F., Sigurdsson, H. H., Sigurjónsdóttir, M., Másson, M., & Stefánsson, E. (2007). Cyclodextrin solubilization of benzodiazepines: formulation of midazolam nasal spray. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 212(1), 29-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-5173(00)00580-9

- Carstensen, J. T., & Rhodes, C. T. (Eds.). (2000). Drug stability: principles and practices. CRC Press.

- Florence, A. T., & Attwood, D. (2015). Physicochemical principles of pharmacy: in manufacture, formulation and clinical use. Pharmaceutical Press.

- White, R., Bradnam, V., & European Association of Hospital Pharmacists. (2015). Handbook of drug administration via enteral feeding tubes. Pharmaceutical Press.

- Budnitz, D. S., Lovegrove, M. C., Shehab, N., & Richards, C. L. (2011). Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(21), 2002-2012. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1103053

- Ruhoy, I. S., & Daughton, C. G. (2008). Pharmaceuticals in the environment: revised conceptual model and regulatory framework. Environmental Health Perspectives, 116(8), 1122-1128. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.11303

- Kummerer, K. (2009). The presence of pharmaceuticals in the environment due to human use-present knowledge and future challenges. Journal of Environmental Management, 90(8), 2354-2366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.01.023

- World Health Organization. (2003). WHO guidelines for good storage and distribution practices for pharmaceutical products. World Health Organization.

- Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. (2019). Good storage and distribution practices for pharmaceutical products. PhRMA Guidelines.

- Gradman, A. H., Cutler, N. R., Davis, P. J., Robbins, J. A., Weiss, R. J., & Wood, B. C. (1989). Efficacy and safety of once-daily lisinopril therapy in elderly hypertensive patients. Archives of Internal Medicine, 149(6), 1421-1425. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1989.00390060117025

- Fletcher, A. E., Bulpitt, C. J., Chase, D. M., Collins, W. C., Furberg, C. D., Goggin, T. K., … & Rajala, S. (1991). Quality of life with three antihypertensive treatments: cilazapril, atenolol, nifedipine. Hypertension, 17(4), 499-508. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.17.4.499

- Simon, S. R., Black, H. R., Moser, M., & Berland, W. E. (2003). Cough and ACE inhibitors. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(15), 1860-1861. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.15.1860

- Jamerson, K., Weber, M. A., Bakris, G. L., Dahlöf, B., Pitt, B., Shi, V., … & Velazquez, E. J. (2008). Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(23), 2417-2428. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0806182

- Lewis, E. J., Hunsicker, L. G., Clarke, W. R., Berl, T., Pohl, M. A., Lewis, J. B., … & Sollinger, H. W. (2001). Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine, 345(12), 851-860. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa011303

- Acker, C. G., Singh, A. R., Flick, R. P., Bernardini, J., Greenberg, A., & Johnson, J. P. (1998). A trial of thrombolysis in acute renal failure (ATTaRF). Kidney International, 54(5), 1734-1739. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00154.x

- Mancia, G., Fagard, R., Narkiewicz, K., Redón, J., Zanchetti, A., Böhm, M., … & Wood, D. A. (2013). 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. European Heart Journal, 34(28), 2159-2219. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht151

- Puddey, I. B., & Beilin, L. J. (2006). Alcohol is bad for blood pressure. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology, 33(9), 847-852. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04452.x

- Houston, M. C. (2011). The role of nutrition and nutraceutical supplements in the treatment of hypertension. World Journal of Cardiology, 3(6), 160-168. https://doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v3.i6.160

- Benetos, A., Safar, M., Rudnichi, A., Smulyan, H., Richard, J. L., Ducimetière, P., & Guize, L. (1997). Pulse pressure: a predictor of long-term cardiovascular mortality in a French male population. Hypertension, 30(6), 1410-1415. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.30.6.1410

- Psaty, B. M., Smith, N. L., Siscovick, D. S., Koepsell, T. D., Weiss, N. S., Heckbert, S. R., … & Furberg, C. D. (1997). Health outcomes associated with antihypertensive therapies used as first-line agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 277(9), 739-745. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03540330061046

How long does it take for lisinopril to start working?

Lisinopril may begin to lower blood pressure within 1 to 2 hours after the first dose, with peak effects typically occurring 6 to 8 hours after administration. However, the full therapeutic benefits for blood pressure control may not be apparent for 2 to 4 weeks of consistent therapy. Individual patient responses can vary significantly, and some patients may require several weeks or months of treatment optimization to achieve target blood pressure goals. Healthcare providers typically recommend regular blood pressure monitoring during the initial treatment period to assess response and make appropriate dose adjustments. Patients should continue taking the medication as prescribed even if they do not immediately notice symptom improvement, as high blood pressure often does not cause noticeable symptoms.[77]

Can I stop taking lisinopril suddenly?

Abrupt discontinuation of lisinopril is generally not recommended, particularly for patients with heart failure or those who have been taking the medication for extended periods. While lisinopril does not typically cause withdrawal symptoms like some other cardiovascular medications, sudden cessation could potentially result in rebound hypertension or worsening of underlying cardiac conditions. Patients who need to discontinue lisinopril should work with their healthcare provider to develop a gradual tapering schedule when appropriate. Alternative antihypertensive medications may need to be initiated before stopping lisinopril to maintain adequate blood pressure control. Emergency situations may require immediate discontinuation, but this should always be done under medical supervision with appropriate monitoring and alternative treatment plans.[78]

What should I do if I develop a persistent cough while taking lisinopril?

A persistent dry cough is one of the most common side effects associated with ACE inhibitor therapy, affecting approximately 10-20% of patients taking lisinopril. This cough is typically nonproductive, may worsen at night, and can develop anywhere from days to months after starting treatment. Patients who develop a bothersome cough should consult with their healthcare provider rather than discontinuing the medication independently. The cough usually resolves within days to weeks after stopping the ACE inhibitor, but alternative medications such as angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) may provide similar cardiovascular benefits without causing cough. Some patients may choose to continue lisinopril despite mild cough if the cardiovascular benefits outweigh the inconvenience. Cough suppressants are generally not effective for ACE inhibitor-induced cough.[79]

Is it safe to take lisinopril with other blood pressure medications?

Lisinopril is frequently prescribed in combination with other antihypertensive medications to achieve optimal blood pressure control, particularly in patients with resistant hypertension or multiple cardiovascular risk factors. Common combination partners include thiazide diuretics, calcium channel blockers, and beta-blockers, each offering complementary mechanisms of action. However, certain combinations require careful monitoring, such as the concurrent use of potassium-sparing diuretics or angiotensin receptor blockers, which may increase the risk of hyperkalemia. The combination of lisinopril with aliskiren is contraindicated in diabetic patients due to increased risks of adverse outcomes. Healthcare providers carefully select medication combinations based on individual patient characteristics, comorbidities, and treatment response. Regular monitoring of blood pressure, kidney function, and electrolyte levels is essential when using combination therapy.[80]

Can lisinopril affect my kidney function?

Lisinopril can have complex effects on kidney function that may be beneficial or harmful depending on individual patient circumstances. In patients with diabetic nephropathy or chronic kidney disease, ACE inhibitors like lisinopril may provide protective effects by reducing intraglomerular pressure and slowing the progression of kidney damage. However, the medication can also cause acute decreases in kidney function, particularly in patients with bilateral renal artery stenosis, severe heart failure, or volume depletion. Regular monitoring of serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate is recommended, especially during treatment initiation and dose adjustments. Small increases in creatinine (up to 30% above baseline) may be acceptable and could indicate beneficial hemodynamic changes. Significant or progressive increases in creatinine may require dose reduction or discontinuation. Patients with pre-existing kidney disease may need dose adjustments based on their level of renal function.[81]

What are the signs of a serious allergic reaction to lisinopril?

Angioedema represents the most serious allergic reaction associated with lisinopril and requires immediate medical attention. Signs of angioedema include swelling of the face, lips, tongue, throat, hands, feet, or genitals, which may develop gradually or rapidly. Difficulty breathing, swallowing, or speaking due to throat swelling constitutes a medical emergency requiring immediate emergency services. Other serious allergic reactions may include widespread skin rash, severe itching, chest tightness, or sudden onset of severe hypotension. Angioedema can occur at any time during lisinopril therapy, even after years of successful treatment without problems. African American patients may have a higher risk of developing angioedema compared to other ethnic groups. Patients who experience any signs of allergic reaction should stop taking lisinopril immediately and seek medical care. Previous episodes of angioedema with any ACE inhibitor contraindicate future use of this medication class.[82]

How should I take lisinopril for best results?

Lisinopril should be taken consistently at the same time each day to maintain steady blood levels and optimize therapeutic effects. The medication can be taken with or without food, as absorption is not significantly affected by meals. Many patients find it helpful to take lisinopril in the morning to align with natural blood pressure rhythms, though some may prefer evening dosing if they experience dizziness. Tablets should be swallowed whole with a full glass of water and should not be crushed, chewed, or split unless specifically recommended by a healthcare provider. Consistency in timing helps maintain steady drug levels and may improve treatment adherence. Patients should continue taking lisinopril even when feeling well, as high blood pressure typically does not cause symptoms. Missing doses should be avoided when possible, but patients should not double up if a dose is missed. Lifestyle modifications such as dietary changes, exercise, and stress management may enhance the effectiveness of lisinopril therapy.[83]

Can I drink alcohol while taking lisinopril?

Moderate alcohol consumption may be acceptable for some patients taking lisinopril, but alcohol can potentially enhance the blood pressure-lowering effects of the medication and increase the risk of dizziness or fainting. Excessive alcohol intake may counteract the beneficial effects of antihypertensive therapy and contribute to elevated blood pressure over time. Patients should discuss their alcohol consumption patterns with their healthcare provider to determine appropriate limits based on their overall health status and treatment goals. Binge drinking or heavy alcohol use should be avoided as it may cause dangerous drops in blood pressure when combined with lisinopril. Some patients may be more sensitive to the interaction between alcohol and ACE inhibitors, particularly when first starting therapy or after dose increases. Dehydration from alcohol consumption may also increase the risk of kidney problems in patients taking lisinopril. Healthcare providers may recommend limiting alcohol intake or avoiding it entirely based on individual patient risk factors.[84]

What foods or supplements should I avoid while taking lisinopril?

Patients taking lisinopril should be cautious with potassium-rich foods and supplements, as ACE inhibitors can increase potassium levels in the blood. While moderate consumption of potassium-containing foods like bananas, oranges, and spinach is generally acceptable, excessive intake combined with lisinopril may lead to hyperkalemia. Salt substitutes containing potassium should be used with caution and only under medical supervision. Patients should avoid potassium supplements unless specifically prescribed by their healthcare provider. Licorice root supplements may interfere with blood pressure medications and should be avoided. Grapefruit juice does not typically interact with lisinopril, unlike some other cardiovascular medications. Patients should maintain adequate hydration but avoid excessive fluid restriction or overhydration. Sodium restriction is often recommended as part of comprehensive hypertension management but should be balanced to avoid dehydration. Healthcare providers may recommend consultation with a registered dietitian to develop appropriate dietary strategies that complement lisinopril therapy.[85]

Is it normal to feel dizzy when starting lisinopril?

Dizziness, particularly when standing up quickly, is a relatively common side effect when starting lisinopril or increasing the dose. This occurs because the medication lowers blood pressure, and the body may need time to adjust to the new blood pressure levels. The dizziness is often most pronounced during the first few days to weeks of treatment and typically improves as the body adapts. Patients can minimize dizziness by rising slowly from sitting or lying positions, staying well-hydrated, and avoiding sudden position changes. If dizziness is severe, persistent, or accompanied by fainting, patients should contact their healthcare provider as dose adjustment may be necessary. The initial dose of lisinopril is often started low and gradually increased to minimize these effects. Elderly patients may be more susceptible to dizziness and may require more gradual dose titration. Patients should avoid driving or operating machinery if experiencing significant dizziness. Most patients find that mild dizziness resolves within a few weeks of consistent therapy.[86]

How long will I need to take lisinopril?

Lisinopril is typically prescribed as a long-term medication for chronic conditions such as hypertension and heart failure, which generally require lifelong management. The duration of therapy depends on the underlying condition being treated and individual patient response. For hypertension, most patients will need to continue ACE inhibitor therapy indefinitely to maintain blood pressure control and cardiovascular protection. Patients with heart failure may also require long-term treatment to maintain cardiac function and prevent disease progression. Some patients who achieve significant lifestyle modifications, such as substantial weight loss or dietary changes, may be able to reduce their medication requirements under medical supervision. However, discontinuation of antihypertensive therapy typically results in return of elevated blood pressure within weeks to months. Regular follow-up appointments allow healthcare providers to assess ongoing need for therapy and make appropriate adjustments. Patients should never discontinue lisinopril without consulting their healthcare provider, as abrupt cessation may result in rebound hypertension or worsening of cardiac conditions.[87]

Disclaimer: This product information is provided for educational purposes only and is not intended to replace professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult with a qualified healthcare provider before starting, stopping, or modifying any medication regimen. The information presented herein does not constitute medical advice and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with a licensed healthcare professional. Individual patient responses to medications may vary significantly, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with appropriate medical supervision. This document does not imply endorsement, recommendation, or guarantee of safety or efficacy for any particular use. Healthcare providers should refer to current prescribing information and clinical guidelines when making treatment decisions.

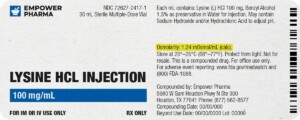

503A vs 503B

- 503A pharmacies compound products for specific patients whose prescriptions are sent by their healthcare provider.

- 503B outsourcing facilities compound products on a larger scale (bulk amounts) for healthcare providers to have on hand and administer to patients in their offices.

Frequently asked questions

Our team of experts has the answers you're looking for.

A clinical pharmacist cannot recommend a specific doctor. Because we are licensed in all 50 states*, we can accept prescriptions from many licensed prescribers if the prescription is written within their scope of practice and with a valid patient-practitioner relationship.

*Licensing is subject to change.

Each injectable IV product will have the osmolarity listed on the label located on the vial.

Given the vastness and uniqueness of individualized compounded formulations, it is impossible to list every potential compound we offer. To inquire if we currently carry or can compound your prescription, please fill out the form located on our Contact page or call us at (877) 562-8577.

We source all our medications and active pharmaceutical ingredients from FDA-registered suppliers and manufacturers.

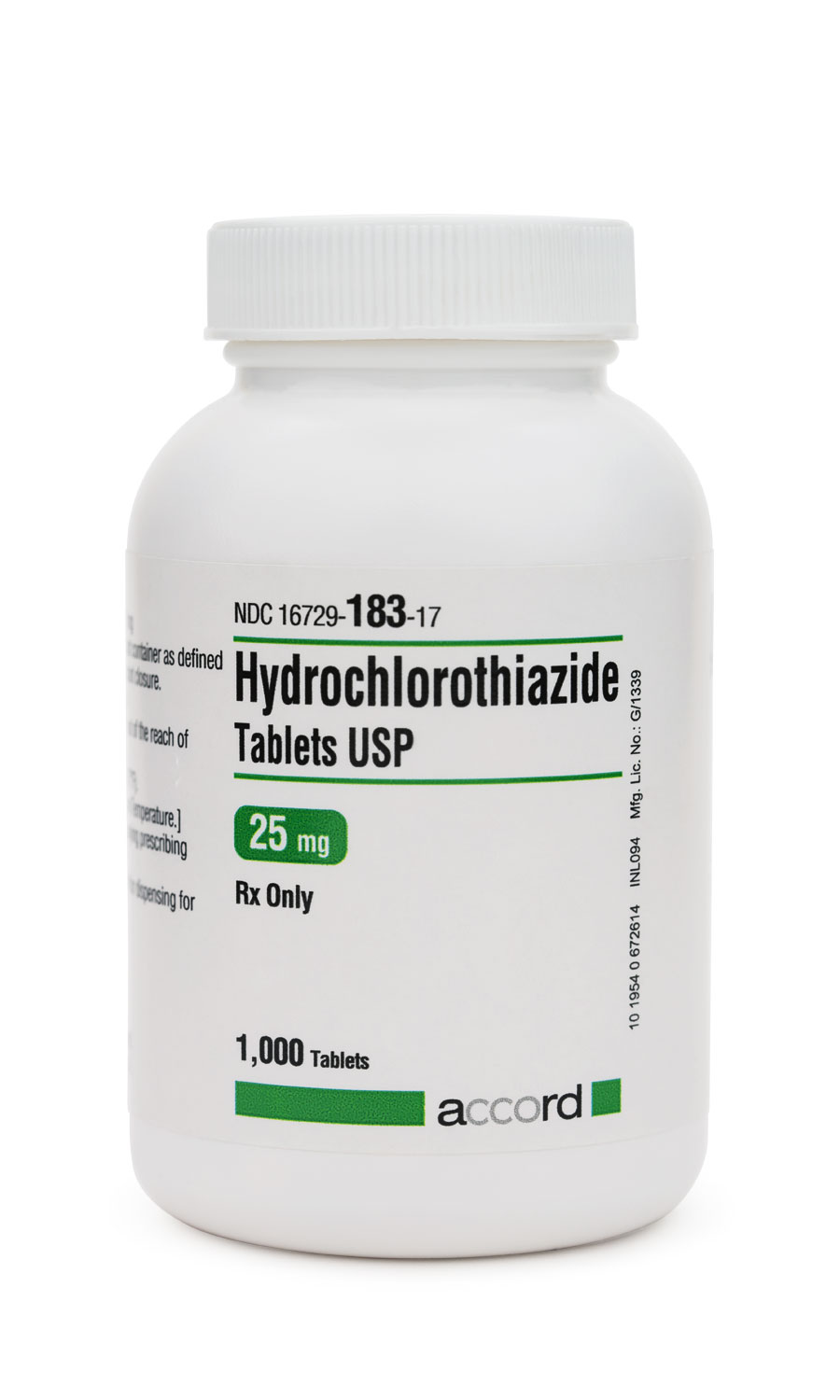

Hydrochlorothiazide / Triamterene Tablets

Hydrochlorothiazide / Triamterene Tablets Hydrochlorothiazide Tablets

Hydrochlorothiazide Tablets Hydrocortisone Tablets

Hydrocortisone Tablets Furosemide Tablets

Furosemide Tablets