Product Overview

† commercial product

Progesterone is a naturally occurring progestin. In the body, it is synthesized in the ovaries, testes, placenta, and adrenal cortex. Progesterone is primarily used to treat amenorrhea, abnormal uterine bleeding, or as a contraceptive.

Progesterone is also used to prevent early pregnancy failure in women with corpus luteum insufficiency, including women undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART). Additionally, the use of progesterone for preterm delivery prophylaxis is being investigated. Preliminary data indicate that progesterone may be effective in preventing preterm delivery in high-risk women, especially those with a history of preterm delivery; however, the optimal dosage and route have not been determined.[1]

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee recommends that if progesterone is to be used for the prevention of preterm delivery, it should only be used in women with a history of spontaneous birth at < 37 weeks gestation, until more data supporting its use in other high-risk women are available.[2] A study in support of the use of vaginal progesterone in women with a short cervix has been published.[3]

Progesterone is available commercially as an intramuscular injection, an intravaginal gel, an intravaginal insert, oral capsules, or a powder for use in extemporaneous preparations (e.g., vaginal suppositories). A progesterone-releasing IUD (Progestasert®) that was inserted once yearly has been discontinued. Progesterone was approved by the FDA in 1939. In May 1998, micronized progesterone capsules for oral administration were approved for secondary amenorrhea; they received a second indication in December 1998 for the prevention of endometrial hyperplasia in postmenopausal women with an intact uterus taking estrogen replacement therapy.

In May 1997, a progesterone vaginal gel (Crinone®) was approved for progesterone supplementation or replacement as part of an ART program for infertile women; a second intravaginal gel, Prochieve™, was released to the US market in 2002. A vaginal insert, Endometrin®, for progesterone supplementation as part of an ART program in infertile women was approved in June 2007.[10]

Progesterone capsules are administered orally. For the prevention of endometrial hyperplasia in postmenopausal women with a uterus who are receiving estrogen therapy, a dose of 200 mg at bedtime is given for 12 days sequentially per 28-day cycle. For the treatment of secondary amenorrhea, progesterone capsules may be given as 400 mg at bedtime for 10 days.[8]

Endogenous progesterone is responsible for inducing secretory activity in the endometrium of the estrogen-primed uterus in preparation for the implantation of a fertilized egg and for the maintenance of pregnancy. It is secreted from the corpus luteum in response to luteinizing hormone. The hormone increases basal body temperature, causes histologic changes in vaginal tissues, inhibits uterine contractions, inhibits pituitary secretion, stimulates mammary alveolar gland tissues, and precipitates withdrawal bleeding in the presence of estrogen. The administration of progesterone to women with adequate estrogen production transforms the uterus from a proliferative to a secretory phase.[36]

The primary contraceptive effect of exogenous progestins involves the suppression of the midcycle surge of luteinizing hormone (LH). The exact mechanism of action, however, is unknown. At the cellular level, progestins diffuse freely into target cells and bind to the progesterone receptor. Target cells include the female reproductive tract, the mammary gland, the hypothalamus, and the pituitary. Once bound to the receptor, progestins slow the frequency of release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus and blunt the pre-ovulatory LH surge, thereby preventing follicular maturation and ovulation.

Overall, progestin-only contraceptives prevent ovulation in 70-80% of cycles; however, the clinical effectiveness ranges 96-98%. This suggests that additional mechanisms may be involved. Other actions of progestins include alterations in the endometrium that can impair implantation and an increase in cervical mucus viscosity which inhibits sperm migration into the uterus. Progesterone administered via intrauterine device (IUD) suppresses proliferation of endometrial tissue. Following removal of the IUD, the endometrium rapidly returns to a normal cyclic pattern and can support pregnancy. Progesterone has minimal estrogenic and androgenic activity.[36]

Do not take this medicine if you have breast cancer, cardiac disease or dementia. Your health care provider needs to know if you have any of these conditions: autoimmune disease like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); blood vessel disease, blood clotting disorder, or suffered a stroke; breast, cervical or vaginal cancer; dementia; diabetes; kidney or liver disease; heart disease, high blood pressure or recent heart attack; high blood lipids or cholesterol; hysterectomy; tobacco smoker; vaginal bleeding; an unusual or allergic reaction to progesterone or other products; pregnant or trying to get pregnant; breast-feeding.

This medicine can cause swelling, tenderness, or bleeding of the gums. Do not drive, use machinery, or do anything that needs mental alertness until you know how this drug affects you. This list may not include all possible contraindications.[8]

Progesterone injection formulations are for intramuscular use only. Never administer via intravenous administration. Hormonal contraceptives have been associated with the development of hepatic tumors. Although this is believed to be an estrogen-mediated effect, progesterone is contraindicated in patients with hepatic disease or hepatic dysfunction. Progesterone is contraindicated in undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding or incomplete abortion. Hormones can cause irregular menstrual bleeding in most women. In general, these irregularities diminish with continuing use.

Women should be counseled regarding irregular menstrual bleeding. Progesterone is contraindicated in patients with pre-existing breast cancer or cancer of reproductive organs, such as cervical cancer, uterine cancer, or vaginal cancer, except as palliative therapy in selected patients. Although progestins reduce the risk of endometrial cancer in patients receiving estrogen replacement therapy, it is unclear whether progestins added to estrogen therapy reduce the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.[4]

Progesterone should be used cautiously in patients with hyperlipidemia. Although hyperlipidemia is associated with estrogen-progestin combinations, the effects of progestin-only oral contraceptives on serum lipids have not been studied. Serum lipoproteins (HDL and LDL) should be monitored during therapy with progesterone. The safety and effectiveness of progesterone have only been established in females of reproductive age.

Use of progesterone in female children before menarche is not usually indicated, and its safety and efficacy in this population is not established. Progesterone is contraindicated in patients with a history of thrombophlebitis or thromboembolic disease (including stroke and myocardial infarction). Although thromboembolic disease is believed to be an estrogen-related effect, studies have shown that patients receiving hormonal contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy regimens containing progestins may have a higher risk of venous thromboembolic (VTE) disease.

Because of the higher risk of thromboembolic disease in tobacco-smoking women, women should be advised not to smoke, particularly if they are over the age of 35 years. Hormonal contraceptives and hormone replacement therapies should also be used cautiously in patients with a history of coronary artery disease, progestin intolerance, or cerebrovascular disease.

Progesterone should be used cautiously in patients with diabetes mellitus. Although the effects appear to be minimal during therapy with progestins, altered glucose tolerance secondary to decreased insulin sensitivity has been reported during hormonal contraceptive therapy. Progesterone should be prescribed cautiously in patients with asthma, congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome or other renal disease, or cardiac disease. Hormonal contraceptives can cause fluid retention and may exacerbate any of the above conditions. Progesterone should be used cautiously in patients with a history of major depression, migraine, or seizure disorder. Progestins may exacerbate these conditions in some patients.

Some cases of seizures following administration of progestins have been reported. An intrauterine device containing progesterone should not be used if there is any infection or inflammation in the female reproductive tract. There is a risk of infection progressing to pelvic inflammatory disease. Exposure to sexually transmitted disease also increases this risk.

Progesterone capsules should not be used in patients with peanut hypersensitivity, as this product is formulated with peanut oil. Progesterone may cause transient dizziness in some patients. Use caution when driving or operating machinery. Estrogen/progestin combination therapy has been found to fail to prevent mild cognitive impairment (memory loss) and to increase the risk of dementia in women 65 years and older.

The WHIMS study, an ancillary study of the WHI trial to assess the effects of estrogen/progestin therapy on cognitive function in geriatric women, found that patients receiving either active treatment or placebo had similar rates of developing mild cognitive impairment. Patients receiving estrogen/progestin combination therapy were more likely than those receiving placebo to be diagnosed with dementia.

The applicability of this finding to women who use estrogen alone or to typical users of hormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms is unclear. Administration of estrogen/progestin combination therapy should be avoided in women 65 years of age and older, and such therapy should not be used to prevent or treat dementia or preserve cognition.[9]

Hormonal contraceptives have been associated with retinal thrombosis. Although this effect is generally believed to be related to estrogen, patients should be monitored carefully for the development of ocular lesions. Progesterone therapy should be discontinued if any unexplained visual disturbance occurs.[9]

Possible interactions include: barbiturates; medicines for sleep or seizures; bexarotene; carbamazepine; ethotoin; ketoconazole; phenytoin; rifampin. This list may not describe all possible interactions. Give your health care provider a list of all the medicines, herbs, non-prescription drugs, or dietary supplements you use. Also tell them if you smoke, drink alcohol, or use illegal drugs. Some items may interact with your medicine.[21]

Vaginal preparations of progesterone (e.g., Crinone®, Endometrin®, and Prochieve®) should not be used with other intravaginal products (e.g., vaginal antifungals such as clotrimazole, miconazole, terconazole, or tioconazole) as concurrent use may alter progesterone release and absorption from the vagina. Separate the times of administration to avoid the interaction. The manufacturers of Crinone and Prochieve indicate that other intravaginal products can be used as long as 6 hours have elapsed either before or after vaginal administration of progesterone.[10][11] Endometrin is generally not recommended for use with other vaginal products (e.g., antifungal products) as this may alter progesterone release and absorption from the vaginal insert and the potential for interaction has not been formally assessed; use other vaginal products if medically necessary, but be aware that the response to Endometrin may be altered.[5]

Drugs that can induce hepatic enzymes can accelerate the rate of metabolism of hormones, including hormonal contraceptives. Pregnancy has been reported during therapy with estrogens, oral contraceptives, or progestins in patients receiving phenytoin concurrently.[12] Women taking both hormones and hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs should report breakthrough bleeding to their prescribers.

An alternate or additional form of contraception should be considered in patients prescribed concomitant therapy with enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants, or higher-dose hormonal regimens may be indicated where acceptable or applicable. The alternative or additional contraceptive agent may need to be continued for one month after discontinuation of the interacting medication. Patients taking these hormones for other indications may need to be monitored for reduced clinical effect while on phenytoin, with dose adjustments made based on clinical efficacy.[12]

Drugs that can induce hepatic enzymes can accelerate the rate of metabolism of hormones, including hormonal contraceptives. Pregnancy has been reported during therapy with estrogens, oral contraceptives, or progestins in patients receiving phenytoin (the active metabolite of fosphenytoin) concurrently.[12][13] Women taking both hormones and hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs should report breakthrough bleeding to their prescribers.

An alternate or additional form of contraception should be considered in patients prescribed concomitant therapy with enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants, or higher-dose hormonal regimens may be indicated where acceptable or applicable. The alternative or additional contraceptive agent may need to be continued for one month after discontinuation of the interacting medication. Patients taking these hormones for other indications may need to be monitored for reduced clinical effect while on fosphenytoin, with dose adjustments made based on clinical efficacy.[12]

Drugs that can induce hepatic enzymes can accelerate the rate of metabolism of hormones, including hormonal contraceptives. Pregnancy has been reported during therapy with estrogens, oral contraceptives, or progestins in patients receiving phenytoin concurrently.[12] A similar interaction may be expected with ethotoin.[14] Women taking both hormones and hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs should report breakthrough bleeding to their prescribers. An alternate or additional form of contraception should be considered in patients prescribed concomitant therapy with enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants, or higher-dose hormonal regimens may be indicated where acceptable or applicable.

The alternative or additional contraceptive agent may need to be continued for one month after discontinuation of the interacting medication. Patients taking these hormones for other indications may need to be monitored for reduced clinical effect while on ethotoin, with dose adjustments made based on clinical efficacy.[14]

Estrogens and progestins are both susceptible to drug interactions with hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs such as carbamazepine. Concurrent administration of carbamazepine with estrogens, oral contraceptives, or progestins may increase the hormone’s elimination.[15][16][17]

Women taking both hormones and hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs should report breakthrough bleeding to their prescribers. If used for contraception, an alternate or additional form of contraception should be considered in patients prescribed hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs, or higher-dose hormonal regimens may be indicated where acceptable or applicable, as pregnancy has been reported in patients taking the hepatic enzyme-inducing drug phenytoin concurrently with hormonal contraceptives.

The alternative or additional contraceptive agent may need to be continued for one month after discontinuation of the interacting medication. Patients taking these hormones for other indications may need to be monitored for reduced clinical effect while on carbamazepine, with dose adjustments made based on clinical efficacy.[17]

Estrogens and progestins are both susceptible to drug interactions with hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs such as barbiturates. Concurrent administration of barbiturates with estrogens, oral contraceptives, non-oral combination contraceptives, or progestins may increase the hormone’s elimination.[10][18][19] Women taking both hormones and hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs should report breakthrough bleeding to their prescribers. If used for contraception, an alternate or additional form of contraception should be considered in patients prescribed hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs.

Higher-dose hormonal regimens may be indicated where acceptable or applicable, as pregnancy has been reported in patients taking the hepatic enzyme-inducing drug phenytoin concurrently with hormonal contraceptives.

The alternative or additional contraceptive agent may need to be continued for one month after discontinuation of the interacting medication. Additionally, epileptic women taking both anticonvulsants and oral contraceptives may be at higher risk of folate deficiency secondary to additive effects on folate metabolism; if oral contraceptive failure occurs, the additive effects could potentially heighten the risk of neural tube defects in pregnancy.[20]

Patients taking these hormones for other indications may need to be monitored for reduced clinical effect while on barbiturates, with dose adjustments made based on clinical efficacy.

Estrogens and progestins are both susceptible to drug interactions with hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs such as rifampin, rifabutin, or rifapentine. Concurrent administration of these drugs with estrogens, oral contraceptives, or progestins may increase the hormone’s elimination.[10][21][22][23]

In addition, free estrogen-hormone concentrations are decreased because rifampin increases estrogenic protein-binding ability. Additionally, like other anti-infectives, rifampin indirectly inhibits the enterohepatic recirculation of estrogen through disruption of gastrointestinal flora. Women taking both hormones and any of these drugs should report breakthrough bleeding to their prescribers; it is estimated that 70% of women taking oral contraceptives and rifampin experience menstrual abnormalities, and 6% become pregnant.[24][25]

If used for contraception, an alternate or additional form of contraception should be considered in patients prescribed rifampin, rifabutin, or rifapentine. Higher-dose hormonal regimens may be indicated where acceptable or applicable. The alternative or additional contraceptive agent may need to be continued for one month after discontinuation of the interacting medication. Patients taking these hormones for other indications may need to be monitored for reduced clinical effect while on rifampin, rifabutin, or rifapentine, with dose adjustments made based on clinical efficacy.

The metabolism of progesterone was inhibited by ketoconazole, a known inhibitor of cytochrome P450 3A4 hepatic enzymes.[8] It has not been determined whether other drugs that inhibit CYP3A4 hepatic enzymes would have a similar effect. Other such drugs include cimetidine, clarithromycin, danazol, diltiazem, erythromycin, fluconazole, itraconazole, troleandomycin, verapamil, and voriconazole.[21][26][27][28][29] (This list is not inclusive of all drugs that inhibit CYP3A4.)

Although specific studies have not been done with progesterone (including the progesterone intrauterine device), an alternative or additional non-hormonal method of birth control is recommended during aprepitant or fosaprepitant treatment and for 28 days after aprepitant treatment is discontinued to avoid the potential for contraceptive failure.[30]

Bromocriptine is used to restore ovulation and ovarian function in amenorrheic women.[31] Progestins can cause amenorrhea and, therefore, counteract the desired effects of bromocriptine. Concurrent use is not recommended.

Food can increase the bioavailability of progesterone administered orally.[8] Mean peak serum concentrations (C_max) were increased slightly when progesterone was administered with or 2 hours after a high-fat breakfast relative to the fasting state. In contrast, when the capsules were administered 4 hours after the high-fat breakfast, there was a significant increase in C_max. There was no effect on the time to maximum serum concentrations (T_max). The effects of food on the pharmacokinetics of progesterone showed high intra- and inter-subject variability.[8]

In a published study, progesterone was given intravenously to patients with advanced malignancies at high doses (up to 10 g over 24 hours) concomitantly with a fixed doxorubicin dose (60 mg/m²) by IV bolus. Enhanced doxorubicin-induced neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were observed.[32] Similar effects may occur with doxorubicin liposomal.

Based on an interaction with tamoxifen, bexarotene capsules may theoretically increase the rate of metabolism and reduce plasma concentrations of other substrates metabolized by CYP3A4, including progestins.[33]

Bosentan is a significant inducer of CYP3A hepatic enzymes.[21][34] Specific interaction studies have not been performed to evaluate the effect of coadministration of bosentan and hormonal contraceptives (oral contraceptives, estrogens, or progestins), including oral, injectable or implantable agents.[34]

Since many of these drugs are metabolized by CYP3A4, there is a possibility of contraceptive failure when bosentan is coadministered.[21][34] Women should not rely on hormonal contraception alone when taking bosentan; bosentan is teratogenic and is contraindicated during pregnancy.[34] Since many of these drugs are metabolized by CYP3A4, a reduction in hormone replacement efficacy is possible when bosentan is coadministered.[34]

Progesterone is known to decrease the uptake of iodide into thyroid tissue.[35] In order to increase thyroid uptake and optimize exposure of thyroid tissue to the radionuclide sodium iodide I-131, consider withholding progesterone prior to treatment with sodium iodide I-131. This list may not include all possible interactions.[35]

The most common adverse reactions occurring during therapy with progesterone include menstrual irregularity, menstrual flow changes, and dysmenorrhea or amenorrhea. These effects may be indistinguishable from pregnancy. Progesterone also causes spotting, breakthrough bleeding, weight gain, nausea, vomiting, breast tenderness or mastalgia, and mild headache.

These adverse effects occur less frequently with progestin-only oral contraceptives compared to combination oral contraceptives. Other reported adverse reactions during therapy include melasma, chloasma, libido decrease, libido increase, breast discharge, cervicitis, galactorrhea, hirsutism, leukorrhea, unusual weakness, and vaginitis.

Post-marketing experiences with oral progesterone include endometrial carcinoma, hypospadias, intrauterine death, menorrhagia, menstrual disorder, metrorrhagia, ovarian cyst, and spontaneous fetal abortion.[36] Additional adverse reactions associated with the intravaginal gel include breast enlargement, dyspareunia, nocturia, perineal pain, dysmenorrhea, premenstrual tension, vaginal dryness, and vaginal discharge.[37] Adverse reactions associated with vaginal inserts include vaginal irritation, vaginal itching, vaginal burning, and vaginal pain/discomfort.[5]

Fluid retention and/or edema may occur in patients receiving progesterone. Patients with heart failure and/or renal disease may experience an exacerbation of their condition. Post-marketing reports of adverse reactions with oral progesterone include facial edema, circulatory collapse, congenital heart disease, hypertension, hypotension, and sinus tachycardia.[36]

Patients receiving progesterone or other hormonal contraceptives can experience emotional lability. This adverse effect may manifest as mental depression, anxiety, frustration, irritability, anger, or other emotional outbursts. Additional CNS and psychiatric adverse events reported include insomnia, aggression, forgetfulness, migraine, tremor, headache, dizziness, drowsiness, and fatigue.

Post-marketing experience reports include convulsions, depersonalization, disorientation, dysarthria, loss of consciousness, paresthesias, sedation, stupor, difficulty walking, syncope, transient ischemic attack, suicidal ideation, and feeling drunk.[36]

The insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD) containing progesterone may result in infection. The risk of infection is greatest within the first 20 days after insertion. Untreated infection may lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, which requires removal of the system and appropriate antibiotic treatment. The patient’s partner may also require antibiotic treatment. Uterine pain may follow initial insertion of the progesterone IUD and usually responds to analgesic therapy. Pain should not persist for more than a few hours after IUD insertion.[5]

Thromboembolic disease is more common in hormonal contraceptive users than in non-users. Previously, thromboembolic disease such as deep venous thrombosis (DVT) appeared to be more related to estrogen therapy than to progestin therapy; however, there is some evidence that different types of progestins are associated with differing rates of venous thromboembolism.

At usual doses, women receiving third-generation progestins (e.g., desogestrel or gestodene) appear to have an increased risk of venous thromboembolic disease compared to women receiving previous-generation progestins.[38][39] The risk is even greater in women with genetic predisposition or family history for venous thromboembolic disease.[40]

Thromboembolism or thrombus formation has also been associated with high doses of progestins. Other rare adverse reactions that may occur during progestin therapy may include pulmonary embolism, retinal thrombosis, hepatoma, hepatitis (with elevated hepatic enzymes), cholestasis, jaundice, and hyperglycemia.[36]

Intramuscular administration of progesterone often causes an injection site reaction. Adverse local reactions include erythema, irritation, pain, and swelling at the site of injection. More general dermatological events have been reported and include alopecia, pruritus, urticaria, acne vulgaris, rash (unspecified), seborrhea, skin discoloration, fever, and hot flashes. Anaphylactoid reactions and hypersensitivity, including dyspnea, rhinitis, asthma, hyperventilation, and throat tightness have been reported.[36][37]

Gastrointestinal adverse reactions reported with progesterone use include abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, dysphagia, eructation, flatulence, gastritis, diarrhea, constipation, anorexia, appetite stimulation, and weight loss. Acute pancreatitis and swollen tongue have been reported post-marketing.[36]

Adverse reactions reported with progesterone use include abnormal gait, arthralgia, choking (with oral formulations), cleft lip, cleft palate, tinnitus, vertigo, cystitis, dysuria, increased urinary frequency, leg pain, musculoskeletal pain, flu-like symptoms, xerophthalmia, benign cyst, purpura, anemia, infection, pharyngitis, sinusitis, urinary tract infection, and conjunctivitis.[36][37]

Progesterone capsules are classified in FDA pregnancy category B. Animal studies involving oral or intravaginal or in utero administration of progesterone have, in general, not indicated evidence of fetal harm. In general, several studies of women exposed to progesterone during pregnancy for luteal support have not demonstrated a significant increase in fetal malformations.

A single case of cleft palate has been reported in an infant exposed to micronized progesterone in utero. Rare cases of fetal death have been reported in women administered micronized progesterone in early pregnancy, but causality has not been established. Only select products are specifically labeled for use to provide luteal support during pregnancy.[5][6]

Crinone progesterone vaginal gel may be used to support early pregnancy as part of an ART program; if pregnancy occurs, the gel is typically continued for 10-12 weeks until placental production of progesterone is adequate to support the pregnancy. Similarly, Endometrin vaginal inserts are used for up to 10 weeks in ART. Progesterone should only be used during early pregnancy under the observation of an ART specialist; data suggest that progesterone may be effective in preventing preterm delivery, especially in high-risk populations.[1][3]

If progesterone is to be used, the ACOG Committee recommends that it should only be used in women with a history of spontaneous birth at < 37 weeks gestation; in addition, the ideal formulation or whether it should be used in other high-risk women is not yet known.[2] Progesterone should not be used if there is ectopic pregnancy, during cases of missed abortion, or during diagnostic tests for pregnancy. In high doses, injectable progesterone is an anti-fertility drug and may chemically induce female infertility.[2]

In general, the American Academy of Pediatrics considers progesterone to be compatible with breast-feeding.[7] Detectable amounts of progestins have been identified in the milk of nursing mothers; in general the presence of progestins in the milk is not expected to have adverse effects on lactation production. However, the effects of progestins present in breast milk on the nursing infant have not been determined.[6][8] The administration of any medication to nursing mothers should take into account the benefit of the drug to the mother and the potential for risk to the breast-fed infant.[7]

Store this medication at 68-77°F (20-25°C) and away from heat, moisture and light. Keep all medicine out of the reach of children. Throw away any unused medicine after the beyond-use date. Do not flush unused medications or pour them down a sink or drain.[36]

- Meis, P. J., Klebanoff, M., Thom, E., et al. (2003). Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. New England Journal of Medicine, 348(24), 2379-2385. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa035140

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. (2003). Committee Opinion No. 291: Use of progesterone to reduce preterm birth. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 102(5 Pt 1), 1115-1116. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14672496/

- Fonseca, E. B., Celik, E., Parra, M., et al. (2007). Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(5), 462-469. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa067815

- Grady, D., Rubin, S. M., Petitti, D. B., et al. (1992). Hormone therapy to prevent disease and prolong life in postmenopausal women. Annals of Internal Medicine, 117(12), 1016-1037. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-1016

- Pharmaceutics International, Inc. (2014, June). Endometrin® (progesterone) vaginal insert [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=2ba50fa9-b349-40cb-9a4b-1af8faa4ec09

- Watson Pharma, Inc. (2011, December). Crinone® (progesterone vaginal gel) [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=75e97aa1-daa4-45f9-b2e2-1a371302914e

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. (2001). Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics, 108(3), 776-789. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.3.776

- Solvay Pharmaceuticals Inc. (1998, December). Prometrium® (progesterone) capsules [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=cf73c385-5173-4b54-af23-069581c5d560

- Shumaker, S. A., Legault, C., Rapp, S. R., et al. (2003). Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women. JAMA, 289(20), 2651-2662. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.20.2651

- Pharmaceutics International, Inc. (2007, June). Endometrin® (progesterone) vaginal insert [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=2ba50fa9-b349-40cb-9a4b-1af8faa4ec09

- Columbia Laboratories, Inc. (2004, October). Prochieve® (progesterone) vaginal gel [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=9f8dc923-65d7-42ff-b718-97e7a7e87822

- Parke-Davis. (1999, August). Dilantin® Kapseals® (extended phenytoin sodium capsules) [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=8848de76-8d74-4620-bcc7-a86a596e5dd9

- Parke-Davis. (2002, June). Cerebyx® (fosphenytoin sodium) [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=d4c36fad-0ba2-4cd4-9c5e-dcf843f38a5a

- Ovation Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (2003, September). Peganone® (ethotoin) [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/medguide.cfm?setid=afcb9d60-3668-3890-5fed-f0794a12509d

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals. (2003, September). Tegretol® (carbamazepine) [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=8d409411-aa9f-4f3a-a52c-fbcb0c3ec053

- Shire US Inc. (2006, July). Carbatrol® (carbamazepine extended-release) [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=bc03e499-5bac-4293-bff4-6864153a624d

- Crawford, P. (2002). Interactions between antiepileptic drugs and hormonal contraception. CNS Drugs, 16(4), 263-272. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200216040-00005

- Berman, M. L., & Green, O. C. (1971). Acute stimulation of cortisol metabolism by pentobarbital in man. Anesthesiology, 34(4), 365-369. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-197104000-00007

- Purepac Pharmaceuticals. (2000, October). Phenobarbital tablets [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=6903e7ef-8b5c-4b64-a87d-62f1f102bc75

- Lewis, D. P., Van Dyke, D. C., Stumbo, P. J., et al. (1998). Drug and environmental factors associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 32(8), 802-817. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.17343

- Hansten, P., & Horn, J. (2014). The top 100 drug interactions: A guide to patient management (2014 ed.). H & H Publications. https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Top_100_Drug_Interactions.html?id=b-NUngEACAAJ

- Kyriazopoulou, V., Parparousi, O., & Vagenakis, A. (1984). Rifampicin-induced adrenal crisis in Addisonian patients receiving corticosteroid replacement therapy. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 59(6), 1204-1206. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-59-6-1204

- DPT Laboratories, Ltd. (2006, December). Elestrin™ (estradiol) gel [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=eff2dea1-f117-11e3-ac10-0800200c9a66

- Archer, J. S. M., & Archer, D. F. (2002). Oral contraceptive efficacy and antibiotic interaction: A myth debunked. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 46(6), 917-923. https://doi.org/10.1067/mjd.2002.120689

- Dickinson, B. D., Altman, R. D., Nielsen, N. H., & Sterling, M. L. (2001). Drug interactions between oral contraceptives and antibiotics. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 98(5 Pt 1), 853-860. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01528-1

- Purdue Pharmaceutical Products LP. (2004, March). Uniphyl® (theophylline) tablets [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=c13bc0b8-7900-4ef4-98ed-e1315a08d95d

- Abbott Laboratories. (2007, March). Biaxin® (clarithromycin) [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=2e899f4a-a2e9-445c-a0ed-6ad811e997e6

- Aventis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (2007, September). Cardizem® CD (diltiazem) [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=e91f9de3-3fdd-0a6b-71ce-53a2cc142816

- Pfizer Inc. (2008, March). VFEND® (voriconazole) [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=bf2e0dfa-d6ca-4961-9627-b666266f58f1

- Merck & Co., Inc. (2007, November). Emend® (aprepitant) capsules [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=f4b2b5d8-5bdf-4ea6-8dfa-1e01d1dbaaf7

- Novartis Pharmaceutical Corp. (2003, March). Parlodel® (bromocriptine) [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=fbf67fc8-8d29-4ae2-a533-75461754c5b1

- Christen, R. D., McClay, E. F., Plaxe, S. C., et al. (1993). Phase I/pharmacokinetic study of high-dose progesterone and doxorubicin. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 11(12), 2417-2426. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1993.11.12.2417

- Ligand Pharmaceuticals Inc. (2003, April). Targretin® (bexarotene) capsules [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=519a44e3-8a93-456c-b71c-894513810d45

- Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc. (2007, February). Tracleer® (bosentan) [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=b60c9c82-e5c7-4e05-98c7-5bbba4af04b2

- Saha, G. B. (1992). Fundamentals of nuclear pharmacy (3rd ed.). Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-2936-7

- Banner Pharmacaps Inc. (2013, November). Progesterone capsule [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=4f918d15-908e-4c3a-94d6-71370da9a116

- Columbia Laboratories, Inc. (2009, November). Prochieve® (progesterone) vaginal gel [Package insert]. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=9f8dc923-65d7-42ff-b718-97e7a7e87822

- Jick, H., Jick, S. S., Gurewich, V., et al. (1995). Risk of idiopathic cardiovascular death and nonfatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives with differing progestagen components. Lancet, 346(8990), 1589-1593. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92065-9

- World Health Organization. (1995). Effect of different progestagens in low-estrogen oral contraceptives on venous thromboembolic disease. Lancet, 346(8990), 1582-1588. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92064-7

- Bloemenkamp, K. W. M., Rosendaal, F. R., Helmerhorst, F. M., et al. (1995). Enhancement by factor V Leiden mutation of risk of deep-vein thrombosis associated with oral contraceptives containing a third-generation progestagen. Lancet, 346(8990), 1593-1596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92066-0

- Women In Balance Institute. (n.d.). Bioidentical progesterone vs. synthetic progestins. https://womeninbalance.org/resources-research/bioidentical-progesterone-vs-synthetic-progestins/

- NFP Physician. (2024). Understanding the difference: Progestins vs. bioidentical progesterone. https://www.nfpphysician.com/post/progestins-vs-bioidentical-progesterone

- Organon USA Inc. (2023). Prometrium (progesterone) capsules [Prescribing information]. DailyMed. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=cf73c385-5173-4b54-af23-069581c5d560

- MedicinesFAQ. (2025). Prometrium: Uses, dosage, side effects, food interaction & FAQ. https://www.medicinesfaq.com/brand/prometrium

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2024, April). Updated clinical guidance for the use of progestogen supplementation for prevention of recurrent preterm birth. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2023/04/updated-guidance-use-of-progestogen-supplementation-for-prevention-of-recurrent-preterm-birth

- Verywell Health. (2022, May 18). Bioidentical hormone replacement therapy: Is it safe and effective? https://www.verywellhealth.com/bioidentical-hormone-replacement-therapy-5324521

- McLean, R. (2019). Amenorrhea: A systematic approach to diagnosis and management. American Family Physician, 100(1), 39-48. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2019/0701/p39.html

- Nolan, B. J., Liang, B., & Cheung, A. S. (2021). Efficacy of micronized progesterone for sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 106(4), e942-e951. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa873

- Prior, J. C., et al. (2005). The effects of progestins on bone density and bone metabolism in early menopausal women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 192(6), 1623-1630. https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(05)00043-8/fulltext

- Mayo Clinic. (2025, June 1). Progesterone (oral route): Proper use & missed doses. https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/progesterone-oral-route/description/drg-20075298

- Simmons, K. B., & Renner, R. M. (2016). Co-administration of St. John’s Wort and hormonal contraceptives: A systematic review. Contraception, 94(6), 668-677. https://www.contraceptionjournal.org/article/S0010-7824(16)30164-0/fulltext

What distinguishes micronized progesterone from synthetic progestins?

Micronized progesterone is bio-identical-its chemical structure is identical to endogenous human progesterone-whereas synthetic progestins are structurally altered molecules that can bind additional steroid receptors and therefore exhibit different metabolic and vascular profiles.[41][42]

How should progesterone capsules be taken relative to meals to optimize absorption?

The FDA-approved Prometrium® label advises taking capsules at bedtime on an empty stomach (≥ 2 h after eating) because a high-fat meal can increase systemic exposure by ~50 % and magnify dizziness or drowsiness.[43]

What laboratory monitoring is advisable during long-term oral progesterone therapy?

Baseline and periodic serum lipid panels (HDL, LDL, triglycerides) and, when clinically indicated, liver-function tests are recommended-especially in patients with pre-existing hyperlipidemia or hepatic disease-because progestogens can unfavorably influence lipid fractions and are contraindicated in active hepatic dysfunction.[44]

What is the current evidence for using progesterone to prevent recurrent preterm birth?

ACOG’s 2024 Practice Advisory states that vaginal progesterone may be considered for patients with a prior spontaneous preterm birth, singleton gestation, and a short cervix, but routine 17-OH-progesterone injections are no longer recommended after the PROLONG trial failed to confirm benefit.[45]

Is oral micronized progesterone considered “bio-identical,” and what does FDA guidance say?

Yes-micronized progesterone is an FDA-approved bio-identical hormone; however, the FDA cautions that compounded “bio-identical hormone therapy” products are not FDA-approved and may lack proven safety or efficacy.[46]

Which conditions must be ruled out before using progesterone to treat secondary amenorrhea?

The differential diagnosis includes pregnancy, thyroid disease, hyperprolactinemia, hypothalamic-pituitary disorders, premature ovarian insufficiency, and structural uterine pathology; these should be excluded with β-hCG, TSH, prolactin, FSH/LH, and pelvic imaging before initiating therapy.[47]

Does progesterone affect sleep quality?

A 2021 systematic review of randomized controlled trials found that oral micronized progesterone (200-300 mg) improved total sleep time and reduced sleep latency, likely via GABA-A modulation by its neuroactive metabolites.[48]

What is known about progesterone and bone density?

Early menopausal trials show that micronized progesterone does not accelerate bone loss and may even modestly attenuate spinal bone-mineral decline when paired with estrogen; longer-term studies are in progress.[49]

What should a patient do after a missed dose?

If the next scheduled dose is > 2 h away, take the missed capsule with food as soon as remembered; if it is almost time for the next dose, skip the missed dose and resume the regular schedule-never double up.[50]

Can herbal supplements like St. John’s Wort interfere with progesterone?

Yes-St. John’s Wort is a potent CYP3A4 inducer that can lower progesterone (and other hormonal contraceptive) levels, increasing the risk of contraceptive failure; backup contraception is advised.[51]

503A vs 503B

- 503A pharmacies compound products for specific patients whose prescriptions are sent by their healthcare provider.

- 503B outsourcing facilities compound products on a larger scale (bulk amounts) for healthcare providers to have on hand and administer to patients in their offices.

Frequently asked questions

Our team of experts has the answers you're looking for.

A clinical pharmacist cannot recommend a specific doctor. Because we are licensed in all 50 states*, we can accept prescriptions from many licensed prescribers if the prescription is written within their scope of practice and with a valid patient-practitioner relationship.

*Licensing is subject to change.

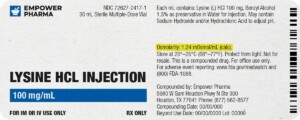

Each injectable IV product will have the osmolarity listed on the label located on the vial.

Given the vastness and uniqueness of individualized compounded formulations, it is impossible to list every potential compound we offer. To inquire if we currently carry or can compound your prescription, please fill out the form located on our Contact page or call us at (877) 562-8577.

We source all our medications and active pharmaceutical ingredients from FDA-registered suppliers and manufacturers.

Progesterone Injection

Progesterone Injection Progesterone Cream

Progesterone Cream Progesterone Troches

Progesterone Troches Estradiol Capsules

Estradiol Capsules Bi-Est Cream

Bi-Est Cream Testosterone Cypionate Injection

Testosterone Cypionate Injection Arousal Cream

Arousal Cream Estradiol Cypionate Injection

Estradiol Cypionate Injection