Product Overview

† commercial product

Sertraline is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant medication that belongs to a class of drugs primarily used to treat various psychiatric and mood disorders. This medication is available as oral tablets in a 50 mg strength formulation. Sertraline was originally developed throughout the 1970s and 1980s by scientists at Pfizer, with FDA approval granted in 1991 for the treatment of major depressive disorder.[1] Since its initial approval, sertraline has become one of the most widely prescribed antidepressant medications in the United States, with tens of millions of Americans currently having prescriptions for this medication.[2]

The therapeutic efficacy of sertraline has been extensively documented through numerous clinical trials and real-world studies. In controlled clinical trials, sertraline has demonstrated significant improvements in depression rating scales compared to placebo, with response rates typically ranging from 50% to 70% in patients with major depressive disorder.[3] A large-scale postmarketing surveillance study involving 1,878 depressed outpatients found that sertraline was both safe and efficacious in routine clinical practice, with treatment response rates exceeding those seen in controlled trials by 10% to 20%.[4] The medication has also shown effectiveness in treating various anxiety disorders, with clinical studies demonstrating its utility in managing obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and social anxiety disorder.[5]

Sertraline’s favorable safety profile has contributed significantly to its widespread clinical use. Unlike tricyclic antidepressants, sertraline does not exhibit significant anticholinergic, antihistamine, or adrenergic blocking activity, which may result in fewer cardiovascular and sedative effects.[6] The medication has been shown to have a minimal risk of overdose compared to older antidepressant classes, and it is the only antidepressant that has demonstrated proven safety in patients with recent myocardial infarction or unstable angina.[7] Clinical studies have consistently shown that sertraline is generally well-tolerated, with most side effects being mild to moderate in severity and often transient in nature.[8]

The onset of therapeutic effects with sertraline may require several weeks to become apparent, which is consistent with the mechanism of action of SSRI medications. While some patients may notice initial improvements in certain symptoms within 1-2 weeks, the full therapeutic benefits typically emerge after 4-6 weeks of consistent treatment.[9] This delayed onset of action appears to be related to the complex neuroadaptive changes that occur in serotonergic neurotransmission following sustained SSRI therapy.[10] Healthcare providers commonly advise patients to continue treatment for at least 6 weeks before evaluating the medication’s effectiveness, as premature discontinuation may prevent patients from experiencing the full therapeutic potential of sertraline.[11]

Sertraline tablets should be administered orally, typically once daily, and may be taken with or without food according to patient preference and tolerability considerations.[100] The medication is available in 50 mg tablet strength, which serves as the standard starting dose for most adult patients with major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.[101] The timing of administration can be flexible, with patients able to take their daily dose either in the morning or evening based on individual response and side effect profile.[102] Patients who experience insomnia or sleep disturbances may benefit from morning dosing, while those who experience daytime sedation might prefer evening administration.[103]

For the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults, the recommended starting dose is 50 mg once daily.[104] This initial dose should be maintained for at least one week to allow for initial adaptation and assessment of tolerability before considering dose adjustments.[105] If the patient demonstrates good tolerability but inadequate therapeutic response after several weeks, the dose may be increased in increments of 50 mg at intervals of at least one week.[106] The maximum recommended daily dose for most indications is 200 mg, though clinical experience suggests that many patients achieve optimal therapeutic benefit at doses between 50-100 mg daily.[107]

Patients with panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and social anxiety disorder typically require a more gradual dose initiation approach due to potential anxiety-provoking effects during treatment initiation. The recommended starting dose for these conditions is 25 mg once daily for the first week, followed by an increase to 50 mg once daily.[108] This lower initial dose helps minimize the potential for increased anxiety or panic symptoms that can sometimes occur when starting SSRI therapy in anxiety-prone individuals.[109] Subsequent dose increases should follow the same weekly increment schedule as used for depression treatment.[110]

For patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, the starting dose is typically 50 mg once daily, with dose increases of 50 mg increments weekly as needed based on clinical response and tolerability.[111] Some patients with OCD may require higher doses than those used for depression, with some individuals benefiting from doses up to the maximum of 200 mg daily.[112] The decision to increase doses should be based on careful assessment of symptom improvement and side effect burden.[113]

Special dosing considerations apply to elderly patients and those with hepatic impairment. Elderly patients may be more sensitive to the effects of sertraline and may experience higher plasma concentrations due to age-related changes in drug metabolism.[114] While no specific dose adjustment is routinely recommended for elderly patients, many clinicians prefer to start with lower doses and titrate more slowly in this population.[115] Patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment should receive reduced starting doses, typically 50% of the standard starting dose, with careful monitoring for signs of drug accumulation.[116]

No dose adjustment is typically necessary for patients with renal impairment, as sertraline elimination is not significantly dependent on kidney function.[117] However, patients with severe renal disease should be monitored carefully for any signs of drug accumulation or unusual side effects.[118] When discontinuing sertraline therapy, gradual dose reduction is preferred over abrupt cessation to minimize the risk of discontinuation symptoms.[119] A typical tapering schedule involves reducing the dose by 50 mg weekly, though some patients may require more gradual tapering over several weeks or months.[120]

Sertraline exerts its pharmacological effects primarily through selective inhibition of the serotonin transporter (SERT), which is responsible for the reuptake of serotonin from synaptic clefts in the central nervous system.[12] By binding to and blocking the serotonin transporter, sertraline prevents the neuronal reuptake of serotonin, thereby increasing the concentration and availability of this neurotransmitter in synaptic spaces.[13] This increased synaptic serotonin concentration leads to enhanced serotonergic neurotransmission, which is believed to contribute to the medication’s antidepressant and anxiolytic effects.[14]

The selectivity of sertraline for the serotonin transporter distinguishes it from older antidepressant medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, which affect multiple neurotransmitter systems. Sertraline demonstrates high affinity for serotonin reuptake transporters while showing very low affinity for norepinephrine uptake transporters and minimal interaction with various neurotransmitter receptors including histamine, acetylcholine, and adrenergic receptors.[15] This selectivity profile contributes to sertraline’s improved tolerability compared to tricyclic antidepressants, as it may result in fewer anticholinergic, antihistaminergic, and cardiovascular side effects.[16]

Interestingly, sertraline also exhibits some activity at the dopamine transporter (DAT), particularly at higher doses of 200 mg and above, where it may occupy approximately 20% of DAT receptors.[17] This dopaminergic activity potentially distinguishes sertraline from other SSRIs and may contribute to its unique clinical profile. Additionally, sertraline shows relatively high activity as an antagonist of the sigma σ1 receptor, though the clinical significance of this interaction remains under investigation.[18]

The therapeutic effects of sertraline appear to involve complex neuroadaptive changes that extend beyond simple serotonin transporter inhibition. Over time, sustained SSRI treatment leads to downregulation of presynaptic 5-HT1A receptors, which may contribute to reduced negative feedback inhibition of serotonin release.[19] This downregulation of inhibitory autoreceptors is associated with improvements in stress tolerance and may contribute to the medication’s antidepressant effects.[20] Additionally, chronic sertraline treatment has been associated with increased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports neuronal growth and plasticity, which may contribute to long-term therapeutic benefits.[21]

The medication undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver, with less than 5% of the drug remaining unchanged in plasma following oral administration.[22] The primary metabolic pathway involves N-demethylation to form desmethylsertraline, which is mediated primarily by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2B6, with contributions from CYP2C19 and other isoforms.[23] While desmethylsertraline retains some pharmacological activity, it is substantially weaker than the parent compound and is not believed to contribute significantly to the clinical effects of sertraline.[24]

Several important contraindications exist for sertraline therapy that healthcare providers must carefully consider before prescribing this medication. The most significant contraindication involves the concurrent use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) or recent discontinuation of MAOI therapy. Sertraline must not be used in combination with any MAOI, including traditional MAOIs such as phenelzine, tranylcypromine, and selegiline, as well as other medications with MAOI properties such as linezolid and methylene blue.[25] A minimum washout period of 14 days must elapse after discontinuing an MAOI before initiating sertraline therapy, and similarly, at least 14 days must pass after stopping sertraline before starting any MAOI.[26] The combination of sertraline with MAOIs can result in serotonin syndrome, a potentially life-threatening condition characterized by mental status changes, autonomic instability, and neuromuscular abnormalities.[27]

Concurrent use of sertraline with pimozide is absolutely contraindicated due to the risk of serious cardiac complications. Pimozide is a typical antipsychotic medication that can prolong the QT interval, and when combined with sertraline, the risk of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death may be significantly increased.[28] This interaction occurs because sertraline inhibits the hepatic metabolism of pimozide, leading to elevated pimozide plasma concentrations and enhanced cardiotoxic effects.[29] Healthcare providers should never prescribe sertraline to patients who are taking pimozide, and alternative treatment options should be considered for both conditions.[30]

Patients with known hypersensitivity to sertraline or any components of the formulation should not receive this medication. Allergic reactions to sertraline, while uncommon, can range from mild skin reactions to severe anaphylactic responses requiring immediate medical intervention.[31] Healthcare providers should carefully assess patients for any history of drug allergies and consider alternative treatments for patients with documented sertraline hypersensitivity.[32]

The liquid concentrate formulation of sertraline contains 12% alcohol and is contraindicated in patients receiving disulfiram therapy. Disulfiram is used to treat alcohol use disorder and works by inhibiting aldehyde dehydrogenase, leading to unpleasant reactions when alcohol is consumed.[33] The alcohol content in sertraline oral solution could potentially trigger a disulfiram-ethanol reaction, resulting in nausea, vomiting, flushing, and other adverse effects.[34] Patients receiving disulfiram who require sertraline therapy should be prescribed the tablet formulation instead of the oral solution.[35]

Caution should be exercised when prescribing sertraline to patients with certain medical conditions, although these may represent relative rather than absolute contraindications. Patients with severe hepatic impairment may require dose adjustments or may not be suitable candidates for sertraline therapy, as the medication undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism.[36] Similarly, patients with unstable cardiac conditions should be carefully evaluated, as sertraline can cause modest prolongation of the QT interval in a dose-dependent manner.[37] While this QT prolongation is generally less pronounced than with some other antidepressants, caution is warranted in patients with pre-existing cardiac rhythm disorders or those taking other medications that affect cardiac conduction.[38]

Sertraline participates in numerous clinically significant drug interactions that require careful consideration and monitoring by healthcare providers. The most serious interactions involve medications that affect serotonergic neurotransmission, potentially leading to serotonin syndrome when used concurrently with sertraline. This life-threatening condition can occur when sertraline is combined with other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, triptans used for migraine treatment, certain opioid medications such as tramadol and fentanyl, lithium, tryptophan supplements, buspirone, amphetamines, and herbal preparations such as St. John’s wort.[39]

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors represent the most dangerous drug interaction with sertraline, as discussed in the contraindications section. However, even reversible MAOIs such as moclobemide require careful consideration and appropriate washout periods.[40] Additionally, certain antibiotics with MAOI properties, particularly linezolid, can interact with sertraline to increase serotonin syndrome risk.[41] Healthcare providers should maintain heightened vigilance when patients require antibiotic therapy while taking sertraline and should consider temporarily discontinuing sertraline if linezolid treatment becomes necessary.[42]

Sertraline can significantly affect the metabolism of other medications through its inhibition of certain cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly CYP2D6. This interaction is particularly relevant for medications with narrow therapeutic indices or those heavily dependent on CYP2D6 metabolism.[43] Thioridazine represents a critical example, as sertraline can increase thioridazine plasma levels, potentially leading to serious cardiac arrhythmias and QT interval prolongation.[44] Similarly, sertraline can affect the metabolism of certain antiarrhythmic drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, and beta-blockers that are CYP2D6 substrates.[45]

The anticoagulant effects of warfarin and other blood-thinning medications may be enhanced when used concurrently with sertraline, potentially increasing the risk of bleeding complications.[46] This interaction appears to result from sertraline’s ability to inhibit platelet aggregation through its effects on platelet serotonin uptake.[47] Patients receiving concurrent therapy with sertraline and anticoagulants require careful monitoring of their international normalized ratio (INR) and clinical signs of bleeding.[48] Similarly, the concurrent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with sertraline may increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, as both drug classes can affect platelet function and gastric mucosal protection.[49]

Sertraline may interact with certain anticonvulsant medications, potentially altering their plasma concentrations and effectiveness. The interaction with phenytoin is particularly noteworthy, as sertraline can increase phenytoin levels, potentially leading to toxicity.[50] Conversely, some anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine and phenobarbital may induce hepatic enzymes responsible for sertraline metabolism, potentially reducing sertraline’s effectiveness.[51] Patients receiving concurrent therapy with sertraline and anticonvulsants may require dose adjustments and careful monitoring of both therapeutic effectiveness and potential toxicity.[52]

Alcohol consumption should be avoided or minimized during sertraline therapy, as the combination may enhance the sedative effects of both substances.[53] While sertraline does not typically cause significant sedation as a monotherapy, the combination with alcohol can impair cognitive function and motor coordination to a greater degree than either substance alone.[54] Additionally, alcohol can potentially interfere with the therapeutic effectiveness of sertraline and may worsen depression and anxiety symptoms.[55]

Sertraline, like all medications, may cause various side effects ranging from mild and transient to more serious and persistent adverse reactions. The side effect profile of sertraline has been extensively characterized through clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance studies, providing healthcare providers with comprehensive information to guide patient counseling and monitoring strategies.[56] Most side effects associated with sertraline are dose-dependent, mild to moderate in severity, and tend to diminish over time as patients develop tolerance to the medication.[57]

The most commonly reported side effects of sertraline, occurring in 5% or more of patients in clinical trials, include gastrointestinal disturbances such as nausea, diarrhea, and indigestion.[58] Nausea is frequently cited as the most prevalent side effect, affecting approximately 25-30% of patients initiating sertraline therapy.[59] This gastrointestinal upset is typically most pronounced during the initial weeks of treatment and often subsides as patients continue therapy.[60] Taking sertraline with food may help reduce the severity of gastrointestinal side effects, and healthcare providers often recommend this strategy for patients experiencing significant nausea.[61]

Neurological side effects commonly associated with sertraline include headache, dizziness, tremor, and sleep disturbances.[62] Sleep-related side effects can manifest as either insomnia or somnolence, with approximately 15-20% of patients experiencing some form of sleep disruption.[63] Some patients may find that taking sertraline in the morning helps reduce insomnia, while others may benefit from evening dosing if daytime sedation occurs.[64] Tremor, typically involving fine motor movements of the hands, affects approximately 10-15% of patients and is usually mild and dose-related.[65]

Sexual dysfunction represents one of the most concerning side effects of sertraline therapy, potentially affecting 20-40% of patients depending on the specific dysfunction and assessment methodology.[66] Common sexual side effects include decreased libido, delayed ejaculation or inability to ejaculate in men, and anorgasmia or delayed orgasm in women.[67] These sexual side effects can significantly impact quality of life and treatment adherence, and healthcare providers should proactively discuss these potential effects with patients.[68] While some sexual side effects may diminish over time, others may persist throughout treatment and potentially even after discontinuation in rare cases.[69]

Sertraline can cause various dermatological reactions, ranging from mild skin irritation to more serious conditions. Increased sweating or hyperhidrosis is relatively common, affecting approximately 10-15% of patients.[70] More serious skin reactions, while rare, can include Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, which require immediate medical attention and discontinuation of the medication.[71] Patients should be advised to report any significant skin changes or rashes to their healthcare provider promptly.[72]

Weight changes can occur with sertraline therapy, though the pattern and magnitude vary considerably among patients. Some individuals may experience weight loss during the initial months of treatment, which may be related to nausea and decreased appetite.[73] However, long-term treatment may be associated with modest weight gain in some patients, particularly those who experience improvement in depression-related appetite changes.[74] Regular monitoring of weight and nutritional status may be appropriate for patients receiving long-term sertraline therapy.[75]

Cardiovascular side effects of sertraline are generally mild but require consideration, particularly in patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions. Sertraline can cause modest, dose-dependent prolongation of the QT interval, though this effect is typically less pronounced than with some other antidepressants.[76] Cases of cardiac arrhythmias, including torsades de pointes, have been reported in post-marketing surveillance, though these events are rare.[77] Patients with risk factors for QT prolongation should receive appropriate cardiac monitoring when initiating sertraline therapy.[78]

The use of sertraline during pregnancy requires careful consideration of both maternal benefits and potential fetal risks, as depression and anxiety disorders during pregnancy can significantly impact both maternal and fetal well-being if left untreated. Sertraline crosses the placental barrier and can be detected in fetal tissues, raising important questions about potential teratogenic effects and neonatal complications.[79] Current evidence suggests that the teratogenic risk associated with sertraline use during the first trimester is likely minimal, with most studies failing to demonstrate increased rates of major congenital malformations.[80]

Large-scale epidemiological studies have provided reassuring data regarding the overall safety of sertraline during early pregnancy. A comprehensive analysis of data from multiple pregnancy registries and cohort studies found no significant increase in the risk of major birth defects when sertraline was used during the first trimester compared to unexposed pregnancies.[81] However, some studies have suggested a possible modest increase in the risk of certain cardiac septal defects, though the absolute risk remains very low and the clinical significance remains unclear.[82] The potential cardiac risks must be weighed against the substantial risks of untreated maternal depression, which can include poor prenatal care, inadequate nutrition, increased substance use, and higher rates of preterm delivery.[83]

The use of sertraline during the third trimester of pregnancy has been associated with a constellation of neonatal complications collectively referred to as poor neonatal adaptation syndrome or neonatal behavioral syndrome.[84] These complications can include respiratory distress, feeding difficulties, temperature instability, jitteriness, irritability, and hypoglycemia.[85] Most of these symptoms are transient and resolve within days to weeks after birth, but some infants may require extended hospitalization and supportive care.[86] The mechanism underlying these neonatal effects is not fully understood but may involve either direct serotonergic effects on the neonate or withdrawal symptoms following in utero exposure.[87]

Some epidemiological studies have suggested a possible association between late pregnancy SSRI exposure and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN), a serious condition that can be life-threatening.[88] However, the absolute risk of PPHN remains very low, estimated at approximately 3-5 cases per 1,000 exposed pregnancies compared to 1-2 cases per 1,000 unexposed pregnancies.[89] The potential increased risk of PPHN must be considered alongside the risks of untreated maternal depression, which can include increased rates of preeclampsia, preterm birth, and low birth weight.[90]

Current clinical guidelines generally recommend that women who are responding well to sertraline therapy and who have moderate to severe depression should consider continuing treatment throughout pregnancy.[91] The decision should involve a comprehensive risk-benefit analysis that considers the severity of the maternal condition, the effectiveness of the current treatment, the availability of alternative treatments, and the patient’s preferences.[92] For women with mild depression or those in remission, gradual tapering of sertraline may be considered, though this approach carries the risk of relapse.[93]

Breastfeeding considerations for sertraline are generally more favorable than pregnancy considerations. Sertraline is present in breast milk, but the concentrations are typically very low, with most studies showing minimal transfer to nursing infants.[94] The milk-to-plasma ratio for sertraline is relatively low, and infant serum concentrations are usually undetectable or present at very low levels.[95] Most authoritative reviews consider sertraline to be one of the preferred antidepressants during breastfeeding, with the American Academy of Pediatrics and other professional organizations generally supporting its use in nursing mothers.[96]

Long-term developmental studies of children exposed to sertraline through breastfeeding have generally been reassuring, with no significant differences in growth, development, or behavioral outcomes compared to unexposed children.[97] However, isolated case reports have described potential adverse effects in nursing infants, including transient sedation or agitation.[98] Healthcare providers should monitor breastfeeding infants for any signs of unusual irritability, feeding problems, or sleep disturbances, particularly during the initial weeks of maternal sertraline therapy.[99]

Proper storage and handling of sertraline tablets is essential to maintain medication stability, potency, and safety throughout the product’s shelf life. Sertraline tablets should be stored at controlled room temperature, specifically between 20°C to 25°C (68°F to 77°F), which represents the optimal temperature range for maintaining chemical stability.[121] Short-term temperature excursions are permitted within the range of 15°C to 30°C (59°F to 86°F), such as during transportation or temporary storage outside of controlled environments.[122] However, prolonged exposure to temperatures outside the recommended range should be avoided, as this may compromise the medication’s potency and effectiveness.[123]

The medication should be stored in its original packaging to protect it from light exposure, which can potentially degrade the active pharmaceutical ingredient over time.[124] The original bottle or blister packaging provides appropriate light protection and helps maintain the integrity of the tablet formulation.[125] Patients should be advised to keep the medication container tightly closed when not in use to prevent moisture exposure, which can also affect tablet stability.[126] Storage in high-humidity environments such as bathrooms should be avoided, as moisture can lead to tablet degradation and potentially compromise therapeutic effectiveness.[127]

Patients should be counseled against storing sertraline tablets in locations subject to extreme temperature variations, such as automobile glove compartments, direct sunlight, or areas near heat sources.[128] Studies examining medication stability under high-temperature conditions suggest that while brief exposure to elevated temperatures may not significantly affect the active ingredient, prolonged exposure can potentially alter the tablet matrix and affect drug release characteristics.[129] Therefore, patients should be advised to store their medication in a cool, dry place away from direct sunlight and heat sources.[130]

All medications, including sertraline, should be stored securely and out of reach of children and pets to prevent accidental ingestion.[131] Child-resistant packaging is typically provided for prescription medications, but patients should be reminded to ensure caps are properly secured after each use.[132] In households with small children, consideration should be given to storing medications in a locked cabinet or other secure location.[133]

When traveling with sertraline, patients should keep the medication in their carry-on luggage when flying to prevent exposure to extreme temperatures that may occur in cargo holds.[134] The medication should be kept in its original prescription bottle with appropriate labeling to facilitate security screening and provide identification in case of medical emergencies.[135] Patients traveling internationally should be aware of medication regulations in their destination countries and may need to carry appropriate documentation regarding their prescription.[136]

Proper disposal of unused or expired sertraline tablets is important for both environmental protection and prevention of accidental exposure. Patients should be advised not to flush medications down the toilet unless specifically instructed to do so by disposal guidelines.[137] The preferred disposal method is through pharmaceutical take-back programs offered by many pharmacies, hospitals, and law enforcement agencies.[138] If take-back programs are not available, patients can dispose of tablets in household trash by mixing them with unpalatable substances such as coffee grounds or cat litter and sealing them in a container before disposal.[139]

- Preskorn SH. Clinical pharmacology of sertraline: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52 Suppl:24-8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2055932/

- Edinoff AN, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse effects: A narrative review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(8):834. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2035- 8377/13/3/38

- Fabre LF Jr, et al. Sertraline safety and efficacy in major depression: a double-blind fixed dose comparison with placebo. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38(9):592-602. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8573661/

- Volz HP, et al. Efficacy, predictors of therapy response, and safety of sertraline in routine clinical practice: prospective, open-label, non-interventional postmarketing surveillance study in 1878 patients. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2-3):271-9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15979151/

- Sertraline – StatPearls. NCBI Bookshelf. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547689/

- DeVane CL, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sertraline. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41(15):1247-66. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12452737/

- Glassman AH, et al. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288(6):701-9. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12169073/

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors – StatPearls. NCBI Bookshelf. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554406/

- Common questions about sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/common-questions-about-sertraline/

- Feighner JP. Mechanism of action of antidepressant medications. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60 Suppl 4:4-11. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10086478/

- Lewis G, et al. The clinical effectiveness of sertraline in primary care and the role of depression severity and duration (PANDA): a pragmatic, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(11):903-914. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31543474/

- Sertraline: Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action. DrugBank Online. Available from: https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB01104

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) Pathway. PMC. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2896866/

- Edinoff AN, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse effects: A narrative review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(8):834. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2035-8377/13/3/38

- Nemeroff CB, Owens MJ. Pharmacologic differences among the SSRIs: focus on monoamine transporters and the HPA axis. CNS Spectr. 2004;9(6 Suppl 4):23-31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15181382/

- Goodnick PJ, Goldstein BJ. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in affective disorders–I. Basic pharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12(3 Suppl B):S5-20. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9808077/

- Narita N, et al. Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with subtypes of sigma receptors in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;307(1):117-9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8757265/

- Hashimoto K. Sigma-1 receptors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: clinical implications of their relationship. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2009;9(3):197-204. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20021354/

- Vidal R, et al. Long-term treatment with fluoxetine induces desensitization of 5-HT1A autoreceptors in rat dorsal raphe neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;613(1-3):75-83. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19376118/

- Blier P, de Montigny C. Current advances and trends in the treatment of depression. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15(7):220-6. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7940983/

- Duman RS, et al. A molecular and cellular theory of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(7):597-606. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9236543/

- DeVane CL, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sertraline. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41(15):1247-66. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12452737/

- Wang JH, et al. The role of CYP2B6 in the stereoselective metabolism of sertraline. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29(12):1589-95. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11717180/

- Alderman J, et al. An open-label study of desmethylsertraline pharmacokinetics in patients taking sertraline. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1992;6(3):151-6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1611010/

- Zoloft (sertraline) interactions. Healthline. Available from:https://www.healthline.com/health/drugs/zoloft-interactions

- MAOI to other antidepressants: switching in adults. NHS. Available from: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/maoi-to-other-antidepressants-switching-in-adults/

- Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1112-20. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15784664/

- Zoloft (sertraline) dosing, indications, interactions. Medscape. Available from: https://reference.medscape.com/drug/zoloft-sertraline-342962

- Alderman CP, et al. Sertraline-pimozide drug interaction. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31(6):776. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9196441/

- Sertraline interactions to avoid. SingleCare. Available from:https://www.singlecare.com/blog/sertraline-interactions/

- Sertraline: Side Effects, Uses, and Dosage. Drugs.com. Available from: https://www.drugs.com/sertraline.html

- Side effects of sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/side-effects-of-sertraline/

- Sertraline – StatPearls. NCBI Bookshelf. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547689/

- Zoloft (sertraline) Label. FDA. Available from: https://www.rxlist.com/zoloft-drug.htm

- Sertraline (oral route) – Side effects & dosage. Mayo Clinic. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/sertraline-oral-route/description/drg 20065940

- Preskorn SH. Clinical pharmacology of sertraline: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52 Suppl:24-8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2055932/

- Beach SR, et al. QTc prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(1):1-13. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23295003/

- Zoloft (Sertraline Hcl): Side Effects, Uses, Dosage. RxList. Available from: https://www.rxlist.com/zoloft-drug.htm

- 9 Sertraline (Zoloft) Interactions You Should Know About. GoodRx. Available from: https://www.goodrx.com/sertraline/interactions

- Clinically Relevant Drug Interactions with Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors. PMC. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9680847/

- Lawrence KR, Adra M, Gillman PK. Serotonin toxicity associated with the use of linezolid: a review of postmarketing surveillance data. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(11):1578- 83. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16652315/

- Huang V, Gortney JS. Risk of serotonin syndrome with concomitant administration of linezolid and serotonin agonists. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(12):1784-93. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17125440/

- Zoloft (sertraline) dosing, indications, interactions. Medscape. Available from: https://reference.medscape.com/drug/zoloft-sertraline-342962

- Alderman CP, et al. Sertraline-thioridazine interaction. Ann Pharmacother. 1996;30(10):1176-7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8893131/

- Preskorn SH, et al. Cytochrome P450 2D6 phenoconversion by sertraline: prevalence and clinical significance. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(5):282-8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17016102/

- Andrade C, et al. Serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and abnormal bleeding: a review for clinicians and a reconsideration of mechanisms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(12):1565-75. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21190637/

- Hergovich N, et al. Paroxetine decreases platelet serotonin storage and platelet function in human beings. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68(4):435-42. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11061584/

- Zeiss R, et al. Risk of bleeding associated with antidepressants: Impact of causality assessment and competition bias on signal detection. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:697463. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34335347/

- de Abajo FJ, García-Rodríguez LA. Risk of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):795-803. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18606952/

- Haselberger MB, et al. Inhibition of platelet MAO-B by the antidepressant and anti Parkinson drug selegiline: biochemical and clinical aspects. Platelets. 2011;22(7):490-7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21599559/

- Spina E, Perucca E. Clinical significance of pharmacokinetic interactions between antiepileptic and psychotropic drugs. Epilepsia. 2002;43 Suppl 2:37-44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11903482/

- Landmark CJ. Antiepileptic drugs in non-epilepsy disorders: relations between mechanisms of action and clinical efficacy. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(1):27-47. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18072813/

- Sertraline (oral route) – Side effects & dosage. Mayo Clinic. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/sertraline-oral-route/description/drg 20065940

- Ramaekers JG, et al. Effects of moclobemide and mianserin on highway driving, psychometric performance and subjective parameters, relative to placebo. Psychopharmacology. 1992;106 Suppl:S62-7. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1546146/

- Petrakis IL, et al. Comorbidity of alcoholism and psychiatric disorders. Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26(2):81-9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12154648/

- Sertraline Side Effects: Common, Severe, Long Term. Drugs.com. Available from: https://www.drugs.com/sfx/sertraline-side-effects.html

- Edinoff AN, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse effects: A narrative review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(8):834. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2035-8377/13/3/38

- Sertraline: Side Effects, Uses, and Dosage. Drugs.com. Available from: https://www.drugs.com/sertraline.html

- Ferguson JM. SSRI Antidepressant Medications: Adverse Effects and Tolerability. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3(1):22-27. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC181155/

- Cascade E, et al. Real-World Data on SSRI Antidepressant Side Effects. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6(2):16-18. Available from:https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2719449/

- Sertraline: MedlinePlus Drug Information. Available from:https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a697048.html

- Sertraline – StatPearls. NCBI Bookshelf. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547689/

- Wilson S, Argyropoulos S. Antidepressants and sleep: a qualitative review of the literature. Drugs. 2005;65(7):927-47. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15892588/

- Common questions about sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/common-questions-about-sertraline/

- Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, et al. Drug-induced tremor: a comprehensive review. J Clin Med. 2021;10(19):4461. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34640465/

- Montejo AL, et al. SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction: fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine in a prospective, multicenter, and descriptive clinical study of 344 patients. J Sex Marital Ther. 1997;23(3):176-94. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9292833/

- Clayton AH, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among newer antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):357-66. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12000211/

- Baldwin DS, et al. Sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant drugs. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006;5(1):75-89. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16370957/

- Csoka AB, Shipko S. Persistent sexual side effects after SSRI discontinuation. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75(3):187-8. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16636635/

- Ghanizadeh A. Sertraline-associated hair loss. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(7):693-4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18664166/

- Sertraline Side Effects: Common, Severe, Long Term. Drugs.com. Available from: https://www.drugs.com/sfx/sertraline-side-effects.html

- Side effects of sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/side-effects-of-sertraline/

- Serretti A, Mandelli L. Antidepressants and body weight: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1259-72. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21062615/

- Fava M, et al. Weight gain and antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61 Suppl 11:37- 41. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10926053/

- Patten SB, et al. The association between major depression prevalence and sex becomes weaker with age. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(2):203-10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26611741/

- Beach SR, et al. QTc prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(1):1-13. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23295003/

- Zoloft (Sertraline Hcl): Side Effects, Uses, Dosage. RxList. Available from: https://www.rxlist.com/zoloft-drug.htm

- Funk KA, Bostwick JR. A comparison of the risk of QT prolongation among SSRIs. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(10):1330-41. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24259638/

- Pregnancy, breastfeeding and fertility while taking sertraline. NHS. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/pregnancy-breastfeeding-and-fertility-while taking-sertraline/

- ACOG Guidelines on Psychiatric Medication Use During Pregnancy and Lactation. AAFP. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2008/0915/p772.html

- Huybrechts KF, et al. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(25):2397-407. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24941178/

- Malm H, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk for major congenital anomalies. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):111-20. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21691169/

- Bonari L, et al. Perinatal risks of untreated depression during pregnancy. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(11):726-35. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15633850/

- Moses-Kolko EL, et al. Neonatal signs after late in utero exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: literature review and implications for clinical applications. JAMA. 2005;293(19):2372-83. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15900008/

- Levinson-Castiel R, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after in utero exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in term infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(2):173-6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16461873/

- Zeskind PS, Stephens LE. Maternal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use during pregnancy and newborn neurobehavior. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):368-75. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14754951/

- Ferreira E, et al. Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine during pregnancy in term and preterm neonates. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):52-9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17200301/

- Chambers CD, et al. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):579-87. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16467545/

- Kieler H, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension in the newborn: population based cohort study from the five Nordic countries. BMJ. 2012;344:d8012. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22240235/

- Wisner KL, et al. Major depression and antidepressant treatment: impact on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(5):557-66. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19289451/

- Yonkers KA, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(5):403-13. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19703633/

- Stewart DE. Clinical practice. Depression during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(17):1605-11. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22029982/

- Cohen LS, et al. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2006;295(5):499-507. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16449615/

- Sertraline – Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). NCBI Bookshelf. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501191/

- Sertraline and Breastfeeding: Review and Meta-Analysis. PMC. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4366287/

- Sachs HC, Committee on Drugs. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e796-809. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23979084/

- Hendrick V, et al. Weight gain in breastfed infants of mothers taking antidepressant medications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(4):410-2. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12716242/

- Hale TW, et al. Discontinuation syndrome in newborns whose mothers took antidepressants while pregnant or breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5(6):283-8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20807106/

- Zoloft and Breastfeeding: Safety and Alternatives. Healthline. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/breastfeeding/zoloft-and-breastfeeding

- Sertraline (oral route) – Side effects & dosage. Mayo Clinic. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/sertraline-oral-route/description/drg 20065940

- Sertraline – StatPearls. NCBI Bookshelf. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547689/

- Common questions about sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/common-questions-about-sertraline/

- Sertraline FAQs: 24 Common Questions Answered. Take Care by Hers. Available from: https://www.forhers.com/blog/sertraline-faqs-25-common-questions-answered

- Zoloft (sertraline) dosing, indications, interactions. Medscape. Available from: https://reference.medscape.com/drug/zoloft-sertraline-342962

- Sertraline Dosage Guide + Max Dose, Adjustments. Drugs.com. Available from: https://www.drugs.com/dosage/sertraline.html

- Sertraline: Uses, Side effects, Dosage, Cost, and More. Healthline. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/sertraline-oral-tablet

- Zoloft dosage: Forms, strengths, how to take, and more. Medical News Today. Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/drugs-zoloft-dosage

- Sertraline: Side Effects, Uses, and Dosage. Drugs.com. Available from: https://www.drugs.com/sertraline.html

- Goddard AW, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):681-6. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11448375/

- How and when to take sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/how-and-when-to-take-sertraline/

- Greenberg BD, et al. Sertraline treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: efficacy and tolerability results from an open-label extension study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(5):192-9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8071273/

- March JS, et al. Sertraline in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(20):1752-6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9842950/

- Koran LM, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7 Suppl):5-53. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17849776/

- Antidepressant efficacy and safety of low-dose sertraline and standard-dose imipramine. PubMed. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11352337/

- Muijsers RB, et al. Sertraline: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder in elderly patients. Drugs Aging. 2002;19(5):377-92. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12093324/

- Preskorn SH. Clinical pharmacology of sertraline: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52 Suppl:24-8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2055932/

- Murdoch D, McTavish D. Sertraline. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential in depression and obsessive compulsive disorder. Drugs. 1992;44(4):604-24. Available from:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1280568/

- Sertraline – StatPearls. NCBI Bookshelf. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547689/

- Fava M, et al. Withdrawal symptoms after selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(2):72-81. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25721705/

- Rosenbaum JF, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(2):77-87. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9646889/

- Sertraline: Uses, Side effects, Dosage, Cost, and More. Healthline. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/sertraline-oral-tablet

- Zoloft (Sertraline Hcl): Side Effects, Uses, Dosage. RxList. Available from: https://www.rxlist.com/zoloft-drug.htm

- Left Zoloft In A Hot Car. Walrus. Available from: https://walrus.com/questions/left zoloft-in-a-hot-car

- Sertraline (Zoloft): Uses & Side Effects. Cleveland Clinic. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/drugs/20089-sertraline-tablets

- Sertraline 50mg tablets – Summary of Product Characteristics. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5760/smpc

- Sertraline: MedlinePlus Drug Information. Available from:https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a697048.html

- Medication Storage Temperature Guidelines. Baystate Health. Available from: https://www.baystatehealth.org/articles/medication-storage-temperature-guidelines

- Sertraline (Zoloft): Uses, Side Effects, Interactions. WebMD. Available from: https://www.webmd.com/drugs/2/drug-1/sertraline-oral/details

- Left Zoloft In A Hot Car. Walrus. Available from: https://walrus.com/questions/left zoloft-in-a-hot-car

- Medication Storage Temperature Guidelines. Baystate Health. Available from: https://www.baystatehealth.org/articles/medication-storage-temperature-guidelines

- Sertraline: MedlinePlus Drug Information. Available from:https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a697048.html

- Sertraline (Zoloft): Uses & Side Effects. Cleveland Clinic. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/drugs/20089-sertraline-tablets

- Sertraline: MedlinePlus Drug Information. Available from:https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a697048.html

- Sertraline: Uses, Side effects, Dosage, Cost, and More. Healthline. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/sertraline-oral-tablet

- Sertraline: Uses, Side effects, Dosage, Cost, and More. Healthline. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/sertraline-oral-tablet

- Medication Storage Temperature Guidelines. Baystate Health. Available from: https://www.baystatehealth.org/articles/medication-storage-temperature-guidelines

- Sertraline: MedlinePlus Drug Information. Available from:https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a697048.html

- Sertraline (Zoloft): Uses & Side Effects. Cleveland Clinic. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/drugs/20089-sertraline-tablets

- Sertraline (Zoloft): Uses & Side Effects. Cleveland Clinic. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/drugs/20089-sertraline-tablets

- Common questions about sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/common-questions-about-sertraline/

- Sertraline FAQs: 24 Common Questions Answered. Take Care by Hers. Available from: https://www.forhers.com/blog/sertraline-faqs-25-common-questions-answered

- Lewis G, et al. The clinical effectiveness of sertraline in primary care and the role of depression severity and duration (PANDA): a pragmatic, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(11):903-914. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31543474/

- Sertraline (oral route) – Side effects & dosage. Mayo Clinic. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/sertraline-oral-route/description/drg 20065940

- Sertraline FAQs: 24 Common Questions Answered. Take Care by Hers. Available from: https://www.forhers.com/blog/sertraline-faqs-25-common-questions-answered

- DeVane CL, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sertraline. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41(15):1247-66. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12452737/

- Sertraline: Side Effects, Uses, and Dosage. Drugs.com. Available from: https://www.drugs.com/sertraline.html

- Sertraline FAQs: 24 Common Questions Answered. Take Care by Hers. Available from: https://www.forhers.com/blog/sertraline-faqs-25-common-questions-answered

- Common questions about sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/common-questions-about-sertraline/

- Sertraline (oral route) – Side effects & dosage. Mayo Clinic. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/sertraline-oral-route/description/drg 20065940

- Common questions about sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/common-questions-about-sertraline/

- Sertraline FAQs: 24 Common Questions Answered. Take Care by Hers. Available from: https://www.forhers.com/blog/sertraline-faqs-25-common-questions-answered

- Serretti A, Mandelli L. Antidepressants and body weight: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1259-72. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21062615/

- Common questions about sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/common-questions-about-sertraline/

- Fava M, et al. Weight gain and antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61 Suppl 11:37- 41. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10926053/

- Common questions about sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/common-questions-about-sertraline/

- Fava M, et al. Withdrawal symptoms after selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(2):72-81. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25721705/

- Rosenbaum JF, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(2):77-87. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9646889/

- Sertraline – StatPearls. NCBI Bookshelf. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547689/

- Common questions about sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/common-questions-about-sertraline/

- Sertraline (Zoloft): Uses & Side Effects. Cleveland Clinic. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/drugs/20089-sertraline-tablets

- Sertraline FAQs: 24 Common Questions Answered. Take Care by Hers. Available from: https://www.forhers.com/blog/sertraline-faqs-25-common-questions-answered

- 9 Sertraline (Zoloft) Interactions You Should Know About. GoodRx. Available from: https://www.goodrx.com/sertraline/interactions

- Sertraline: MedlinePlus Drug Information. Available from:https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a697048.html

- Sertraline interactions to avoid. SingleCare. Available from:https://www.singlecare.com/blog/sertraline-interactions/

- Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1112-20. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15784664/

- Sertraline (Zoloft): Uses, Side Effects, Interactions. WebMD. Available from: https://www.webmd.com/drugs/2/drug-1/sertraline-oral/details

- Common questions about sertraline. NHS. Available from:https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/sertraline/common-questions-about-sertraline/

- Volz HP, et al. Efficacy, predictors of therapy response, and safety of sertraline in routine clinical practice: prospective, open-label, non-interventional postmarketing surveillance study in 1878 patients. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2-3):271-9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15979151/

- Sertraline – StatPearls. NCBI Bookshelf. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547689/

How long does it take for sertraline to start working?

Sertraline may begin to show initial effects within 1-2 weeks of starting treatment, but the full therapeutic benefits typically emerge after 4-6 weeks of consistent daily use.[140] Some patients may notice improvements in sleep, appetite, and energy levels before experiencing mood improvements.[141] It is important to continue taking sertraline as prescribed even if improvements are not immediately apparent, as the medication requires time to achieve optimal effectiveness.[142]

Can I take sertraline with food?

Yes, sertraline tablets can be taken with or without food according to patient preference.[143] Taking the medication with food may help reduce gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, which is particularly common during the initial weeks of treatment.[144] There are no significant interactions between sertraline and food that would affect the medication’s absorption or effectiveness.[145]

What should I do if I miss a dose of sertraline?

If you miss a dose of sertraline, take it as soon as you remember, unless it is close to the time for your next scheduled dose.[146] Do not take two doses at the same time or take extra medication to make up for a missed dose.[147] If you frequently forget doses, consider setting reminders or speaking with your healthcare provider about strategies to improve medication adherence.[148]

Is it safe to drink alcohol while taking sertraline?

Alcohol consumption should be avoided or significantly limited while taking sertraline, as the combination may enhance sedative effects and impair cognitive function.[149] Additionally, alcohol can potentially interfere with sertraline’s therapeutic effectiveness and may worsen symptoms of depression or anxiety.[150] Patients should discuss their alcohol consumption habits with their healthcare provider to receive personalized guidance.[151]

Can sertraline cause weight gain or weight loss?

Weight changes can occur with sertraline therapy, though the pattern varies among individuals.[152] Some patients may experience initial weight loss due to nausea and decreased appetite during the first weeks of treatment.[153] Long-term treatment may be associated with modest weight gain in some patients, particularly those whose depression previously affected their appetite.[154] Regular monitoring and discussion with healthcare providers can help address any concerning weight changes.[155]

How should I stop taking sertraline?

Sertraline should never be stopped abruptly, as this may cause discontinuation symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, headache, and electric shock-like sensations.[156] Healthcare providers typically recommend gradual dose reduction over several weeks or months, depending on the individual patient’s circumstances.[157] The tapering schedule should always be supervised by a qualified healthcare professional.[158]

Will sertraline affect my ability to drive or operate machinery?

Sertraline may cause dizziness, drowsiness, or other side effects that could impair your ability to drive safely or operate machinery.[159] It is recommended to avoid these activities until you know how sertraline affects you personally.[160] Most patients find that any initial impairment diminishes as they adjust to the medication.[161]

Can I take other medications while using sertraline?

Many medications can be safely used with sertraline, but some combinations require careful monitoring or should be avoided entirely.[162] It is essential to inform all healthcare providers about your sertraline therapy and to discuss any new medications, including over-the-counter drugs and supplements, before starting them.[163] Your pharmacist can also provide valuable guidance about potential drug interactions.[164]

What are the most serious side effects I should watch for?

While most side effects of sertraline are mild, you should seek immediate medical attention if you experience signs of serotonin syndrome (agitation, hallucinations, rapid heart rate, muscle stiffness), severe allergic reactions (difficulty breathing, swelling of face or throat), or any thoughts of self-harm.[165] Additionally, unusual bleeding, severe skin reactions, or significant changes in heart rhythm should be reported to healthcare providers promptly.[166]

Is sertraline safe for long-term use?

For most patients, sertraline is considered safe for long-term use when appropriately monitored by healthcare providers.[167] Many individuals require extended treatment to maintain therapeutic benefits and prevent symptom recurrence.[168] Regular follow-up appointments allow for ongoing assessment of treatment effectiveness and monitoring for any long-term effects.[169]

Disclaimer: This product information is provided for educational purposes only and is not intended to replace professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult with a qualified healthcare provider before starting, stopping, or modifying any medication regimen. The information presented herein does not constitute medical advice and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with a licensed healthcare professional. Individual patient responses to medications may vary significantly, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with appropriate medical supervision. This document does not imply endorsement, recommendation, or guarantee of safety or efficacy for any particular use. Healthcare providers should refer to current prescribing information and clinical guidelines when making treatment decisions.

503A vs 503B

- 503A pharmacies compound products for specific patients whose prescriptions are sent by their healthcare provider.

- 503B outsourcing facilities compound products on a larger scale (bulk amounts) for healthcare providers to have on hand and administer to patients in their offices.

Frequently asked questions

Our team of experts has the answers you're looking for.

A clinical pharmacist cannot recommend a specific doctor. Because we are licensed in all 50 states*, we can accept prescriptions from many licensed prescribers if the prescription is written within their scope of practice and with a valid patient-practitioner relationship.

*Licensing is subject to change.

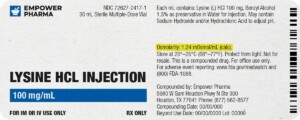

Each injectable IV product will have the osmolarity listed on the label located on the vial.

Given the vastness and uniqueness of individualized compounded formulations, it is impossible to list every potential compound we offer. To inquire if we currently carry or can compound your prescription, please fill out the form located on our Contact page or call us at (877) 562-8577.

We source all our medications and active pharmaceutical ingredients from FDA-registered suppliers and manufacturers.

Ketamine ODT

Ketamine ODT Ketamine Troches

Ketamine Troches Ketamine HCL Injection

Ketamine HCL Injection Mirtazapine Tablets

Mirtazapine Tablets Thyroid Desiccated Porcine Capsules

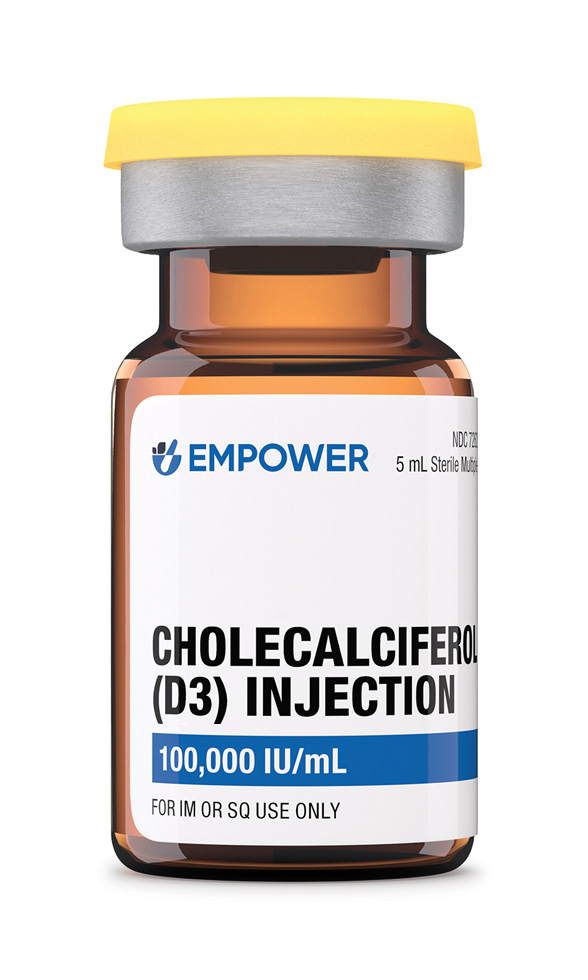

Thyroid Desiccated Porcine Capsules Vitamin D3 (Cholecalciferol) Capsules

Vitamin D3 (Cholecalciferol) Capsules Cholecalciferol (D3) Injection

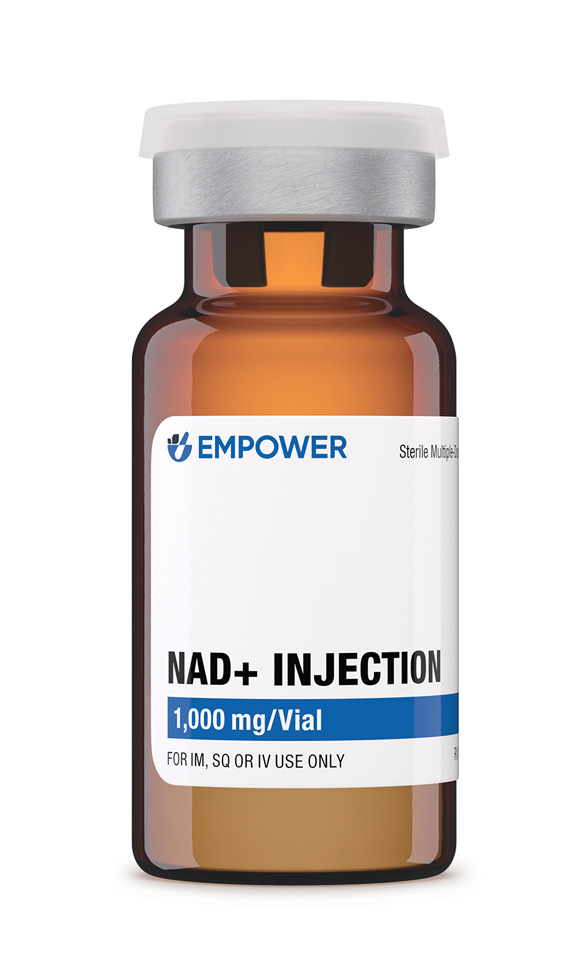

Cholecalciferol (D3) Injection NAD+ Injection (Lyo)

NAD+ Injection (Lyo) Testosterone Cypionate Injection

Testosterone Cypionate Injection