Product Overview

Rapamycin, also known by its International Non-proprietary Name sirolimus, is a macrolide lactone originally isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus found in soil samples from Easter Island.

The compound’s potent antiproliferative and immunosuppressive properties led to its development as an oral agent for the prophylaxis of organ-rejection episodes and for a growing range of investigational indications including vascular stent coatings, rare pulmonary diseases, and selected dermatologic disorders.[1]

Because commercial strengths rarely align with individualized regimens in research or specialty practice, 503A-licensed pharmacies compound rapamycin into unit-dose gelatin capsules such as 1.75 mg and 2.25 mg to facilitate micro-titration, support protocol flexibility, and minimize excipient exposure.

Each batch is prepared under USP <795> conditions, with potency and microbiological testing performed according to current good compounding practice to ensure that prescribers receive a consistent, prescription-only product tailored to patient-specific needs.[2]

Adult transplant prophylaxis typically begins with a 6 mg oral loading dose followed by 2 mg once daily, titrated to therapeutic troughs in concert with concomitant calcineurin inhibitor levels; monotherapy or renal-sparing regimens may require higher targets. For investigational aging studies, once-weekly or intermittent micro-dosing schedules are under exploration but remain off-label and should be supervised within research protocols.

Therapeutic drug monitoring using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry is preferred over immunoassay to avoid cross-reactivity with active metabolites.[13] Compounded capsule strengths of 1.75 mg and 2.25 mg permit fine-grained adjustments when standard 0.5 mg, 1 mg, or 2 mg commercial tablets are unsuitable, helping clinicians align exposure with clinical or investigational endpoints while minimizing waste and pill burden.[14]

At the molecular level, rapamycin forms a ternary complex with the immunophilin FK-binding protein 12 (FKBP-12) and subsequently binds to the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), a serine/threonine kinase pivotal for cell-cycle progression from G₁ to S phase.[3]

Inhibition of mTORC1 down-regulates translation of key messenger RNAs governing T-cell activation, B-cell differentiation, angiogenesis, and autophagy, thereby exerting cytostatic rather than cytotoxic effects-a distinction that underpins its synergy with calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids in transplant protocols.

Pharmacokinetic studies reveal rapid oral absorption but nonlinear dose-exposure relationships attributable to saturable metabolism and high intra-patient variability, necessitating therapeutic drug monitoring to maintain trough concentrations typically between 5 and 15 ng/mL for immunosuppression.[4]

Rapamycin is contraindicated in individuals with a known hypersensitivity to sirolimus, its derivatives, or formulation components; case reports describe immune-mediated pneumonitis presenting with fever, dyspnea, and radiographic infiltrates that resolve upon discontinuation.[5]

Additional contraindications include severe hepatic impairment without dosage adjustment, uncontrolled hyperlipidemia, and situations where profound antiproliferative effects could impair tissue repair, such as major surgery or poorly healing wounds; expert consensus highlights ongoing debate regarding perioperative use, especially in abdominal or thoracic procedures where dehiscence risk is heightened.[6]

Rapamycin is extensively metabolized by cytochrome P450-3A4 and transported by P-glycoprotein; potent inducers such as rifampin can reduce whole-blood concentrations by more than 90 %, prompting dramatic dosage escalations or substitution with alternative antimycobacterial therapy.[7]

Conversely, competitive inhibitors like voriconazole produce supra-therapeutic exposures that may precipitate thrombocytopenia, mucositis, or nephrotoxicity, underscoring the importance of preemptive trough checks and dose adjustments when azoles, macrolides, or protease inhibitors are initiated or withdrawn.[8]

The adverse-event profile is dominated by hematologic and metabolic toxicities; clinical reviews consistently describe dose-related thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, oral aphthous ulcers, and impaired wound healing, alongside a characteristic acneiform or seborrheic dermatosis that may require topical therapy or dose reduction.[9]

Metabolic derangements are common: hypertriglyceridemia, elevated LDL-cholesterol, and new-onset proteinuria have been linked to rapamycin-mediated inhibition of lipid-handling enzymes and glomerular podocyte signaling, with observational studies documenting triglyceride increases exceeding 100 % within six weeks of initiation.[10]

While animal data demonstrate embryofetal toxicity at exposures near the human therapeutic range, controlled human data remain limited. Registry analyses of transplant recipients inadvertently exposed in the first trimester report higher rates of spontaneous abortion and prematurity compared with calcineurin inhibitors, though confounding by comedications and organ dysfunction complicates causal inference.[11]

In lymphangioleiomyomatosis cohorts, discontinuation 8-12 weeks before conception appears to mitigate fetal growth restriction, yet residual uncertainty has led expert groups to recommend avoidance throughout gestation and lactation unless maternal benefit clearly outweighs potential harm.[12]

Rapamycin capsules should be stored at controlled room temperature, 20 - 25 °C (68 - 77 °F, and protected from high humidity and direct light. Frozen storage below −20 °C is not recommended for finished capsules; however, bulk active pharmaceutical ingredient retains stability through at least one freeze-thaw cycle without significant assay drift, provided moisture exclusion is maintained during handling.[16]

- Gallant-Haidner, H. L., Trepanier, D. J., Freitag, D. G., & Yatscoff, R. W. (2000). Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, 22(1), 31-35. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007691-200002000-00006

- Trepanier, D. J., Gallant-Haidner, H. L., & Yatscoff, R. W. (2001). Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 40(2), 85-103. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200140020-00002

- Sehgal, S. N. (2003). Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 88(3), 571-576. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.10361

- Jusko, W. J. et al. (2012). CPT: Pharmacometrics & Systems Pharmacology, 1, e9. https://doi.org/10.1038/psp.2012.18

- Howard, L. et al. (2006). Chest, 129(6), 1718-1721. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.129.6.1718

- Alsina, J., & Grinyó, J. M. (2003). Transplantation, 75(6), 741-742. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.tp.0000046766.12404.f9

- Yates, P. J. et al. (2011). Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation, 22(1), 178-181. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-2442.74340

- Bemer, M. J. et al. (2016). Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, 38(2), 236-240. https://doi.org/10.1097/FTD.0000000000000254

- Nguyen, L. S. et al. (2019). Drug Safety, 42(7), 813-825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-019-00810-9

- Morrisett, J. D. et al. (2002). Journal of Lipid Research, 43(8), 1170-1180. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12177161

- Sifontis, N. M. et al. (2006). Transplantation, 82(12), 1698-1702. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.tp.0000252683.74584.29

- Liu, G. et al. (2021). Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 16, 503. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01776-7

- Shaw, L. M., Kaplan, B., & Brayman, K. L. (2000). Clinical Therapeutics, 22(Suppl B), B1-B13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2918(00)89018-9

- Oberbauer, R. et al. (2020). Annals of Transplantation, 25, e923536. https://doi.org/10.12659/AOT.923536

- Vethe, N. T. et al. (2008). Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, 30(4), 473-478. https://doi.org/10.1097/FTD.0b013e31817da73b

- Shipkova, M. et al. (2000). Clinical Chemistry, 46(9), 1395-1404. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/46.9.1395

- Hoogendijk, A. J. et al. (2012). New England Journal of Medicine, 367(4), 329-338. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1204166

- Gallelli, G. et al. (2024). Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism Case Reports, 2(11), luae193. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcemcr/luae193

- Wishart, D. S. et al. (2022). DrugBank (DB00877). https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00877

- DermNet New Zealand. (2023). Sirolimus factsheet. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/sirolimus

- Hempel, G. et al. (2017). Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, 39(4), 330-337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-017-0403-0

- McCormack, F. X. et al. (2011). New England Journal of Medicine, 364(17), 1595-1606. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1100391

- Lee, J. H. et al. (2005). Nephrology, 10(6), 534-540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00493.x

- Dunkelberg, J. C. et al. (2003). Liver Transplantation, 9(5), 477-483. https://doi.org/10.1053/jlts.2003.50079

- Stein, C. M. et al. (1996). Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 60(6), 656-666. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8770969

- Thomusch, O. et al. (2015). Transplantation Research, 4, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13737-015-0028-6

How does rapamycin’s immunosuppressive action translate into reduced post-transplant skin-cancer rates?

By attenuating mTOR-driven keratinocyte proliferation, long-term use has been correlated with fewer cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas.[17]

Is severe hypertriglyceridemia reversible after stopping rapamycin?

Case reports show normalization of triglycerides within weeks once the drug is withdrawn and lipid-lowering therapy instituted.[18]

Does rapamycin appear in routine drug interaction checkers?

Specialized databases classify it as a major substrate of CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein, warranting manual review of every new prescription.[19]

Why do some clinicians prefer topical over systemic formulations for dermatologic use?

Topical application targets cutaneous mTOR without systemic immunosuppression, reducing infection risk.[20]

Can therapeutic drug monitoring be performed with dried blood spots?

Emerging assays using high-resolution mass spectrometry show promising accuracy for remote sampling.[21]

Is weekly dosing equivalent to daily dosing for longevity research?

Early pilot studies in healthy adults suggest distinct pharmacodynamic signatures, so regimens are not interchangeable.[22]

Are drug-induced mouth ulcers preventable?

Good oral hygiene and topical corticosteroid rinses may reduce incidence but do not eliminate risk.[23]

Does rapamycin affect vaccine effectiveness?

mTOR inhibition can blunt antibody titers; delaying live vaccines until trough levels are low is prudent.[24]

What explains the early acne-like rash?

Inhibition of sebocyte lipid synthesis alters follicular homeostasis, promoting inflammatory lesions.[25]

Can rapamycin be used in chronic kidney disease of non-immune origin?

Nephrology reviews caution that proteinuria may worsen, so risks must be weighed against antiproliferative benefits.[26]

Disclaimer: This compounded medication is prepared under section 503A of the U.S. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Safety and efficacy for this formulation have not been evaluated by the FDA. Therapy should be initiated and monitored only by qualified healthcare professionals.

503A vs 503B

- 503A pharmacies compound products for specific patients whose prescriptions are sent by their healthcare provider.

- 503B outsourcing facilities compound products on a larger scale (bulk amounts) for healthcare providers to have on hand and administer to patients in their offices.

Frequently asked questions

Our team of experts has the answers you're looking for.

A clinical pharmacist cannot recommend a specific doctor. Because we are licensed in all 50 states*, we can accept prescriptions from many licensed prescribers if the prescription is written within their scope of practice and with a valid patient-practitioner relationship.

*Licensing is subject to change.

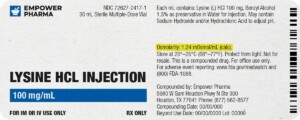

Each injectable IV product will have the osmolarity listed on the label located on the vial.

Given the vastness and uniqueness of individualized compounded formulations, it is impossible to list every potential compound we offer. To inquire if we currently carry or can compound your prescription, please fill out the form located on our Contact page or call us at (877) 562-8577.

We source all our medications and active pharmaceutical ingredients from FDA-registered suppliers and manufacturers.

Anti-Aging Siro Gel

Anti-Aging Siro Gel Resveratrol Capsules

Resveratrol Capsules Methylene Blue Capsules

Methylene Blue Capsules Tirzepatide / Niacinamide Injection

Tirzepatide / Niacinamide Injection Cyanocobalamin (Vitamin B12) Injection

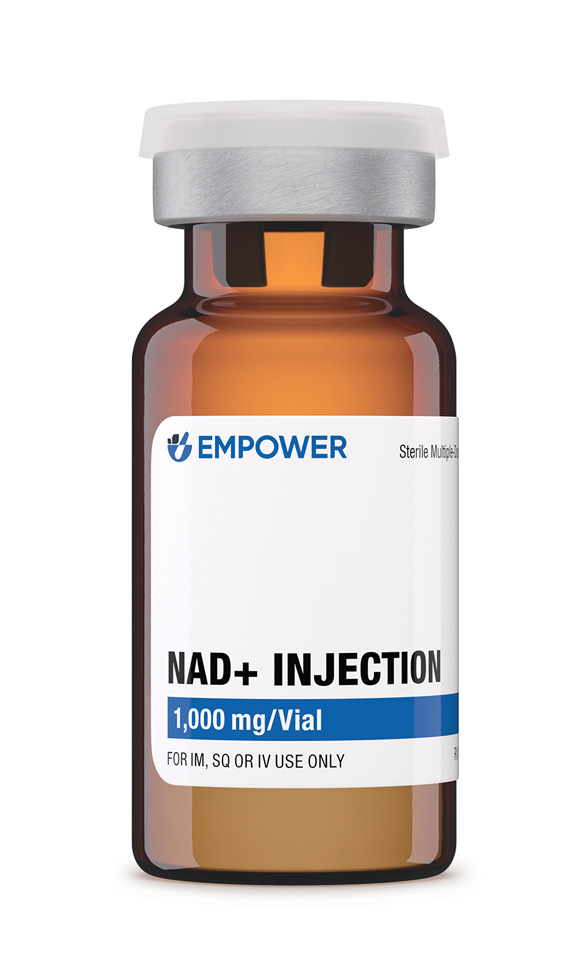

Cyanocobalamin (Vitamin B12) Injection NAD+ Injection (Lyo)

NAD+ Injection (Lyo) NAD+ Cream

NAD+ Cream