Product Overview

† commercial product

Estradiol is the predominant biologically active estrogen in humans and a critical modulator of reproductive, skeletal, cardiovascular, and neuro-endocrine function throughout adult life.[1]

When ovarian production declines after natural menopause, bilateral oophorectomy, gonadotoxic chemotherapy, or primary ovarian insufficiency, compounded estradiol capsules prepared under section 503A enable clinicians to restore physiologic hormone concentrations using patient-specific doses and excipient profiles that may differ from commercial tablets.[2]

The compounded formulation employs micronized USP-grade estradiol dispersed in a cellulose base, promoting rapid disintegration and predictable intestinal absorption while avoiding lactose, dyes, or magnesium stearate that can provoke intolerance in sensitive individuals.[3]

Oral estradiol undergoes extensive first-pass conjugation in the liver, so only about 5%-10% of an administered dose reaches systemic circulation unchanged; nevertheless, a 1 mg capsule yields mean peak serum levels near 70 pg mL⁻¹ within six hours, sufficient to relieve moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms in most users.[4]

Pharmacokinetic variability is wide-dietary fat may increase exposure by roughly one quarter, and CYP3A4 polymorphisms can alter steady-state concentrations fourfold, necessitating individualized titration guided by symptom diaries, serum estradiol-to-estrone ratios, and endometrial monitoring.[5]

Beyond alleviating hot flashes, oral estradiol improves vulvovaginal atrophy, preserves bone mineral density, and may enhance sleep quality and mood, yet systemic treatment introduces cardiometabolic and oncologic trade-offs whose magnitude depends on age at initiation, dose, route, and comorbid risk factors.[6]

Randomized trials comparing oral and transdermal routes show broadly equivalent symptom relief but persistent route-specific differences in hepatic protein synthesis, C-reactive-protein induction, and coagulation factor expression, underscoring the need for individualized route selection.[7]

The compounded strengths-0.75 mg, 1.25 mg, and 1.75 mg-allow for half-step titration between the fixed 0.5 mg, 1 mg, and 2 mg commercial tablets, facilitating gradual escalation or de-escalation over six- to eight-week intervals until the lowest dose that controls symptoms is identified.[8]

Potency variation for each strength remains within ±5 % when stored correctly, as verified by high-performance-liquid-chromatography assay, providing prescribers with confidence in dose reproducibility across refills.[9]

For menopausal vasomotor symptoms, most clinicians initiate therapy at 0.5 mg to 1 mg once daily, titrating in 0.25 mg to 0.5 mg increments every six to eight weeks until the lowest effective dose maintains symptom control, rarely exceeding 2 mg daily.[31]

Cyclic regimens (25 days on, 3-5 days off) facilitate withdrawal bleeding surveillance in women with a uterus who receive cyclic oral progesterone; continuous combined regimens use daily micronized progesterone 100 mg to mitigate endometrial-hyperplasia risk, with annual ultrasonography or biopsy for abnormal bleeding.[32]

Estradiol binds with nanomolar affinity to nuclear estrogen receptors α and β, promoting receptor dimerization, translocation to estrogen-response elements, and recruitment of co-regulators that modulate the transcription of genes involved in vascular tone, lipid metabolism, bone remodeling, and thermoregulatory set points.[10]

The hormone also activates membrane-associated G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER), triggering second-messenger cascades that rapidly augment nitric oxide release, influence intracellular calcium, and provide neuroprotective signals independent of gene transcription.[11]

After gastrointestinal absorption, estradiol is conjugated to estrone sulfate and glucuronides, stored in enterohepatic reservoirs, and intermittently deconjugated by intestinal microbiota before reabsorption-mechanisms that prolong exposure for several days after a missed dose.[12]

Oxidative metabolism occurs chiefly via CYP3A4 and 17β-hydroxysteroid-dehydrogenase type 2; polymorphisms in these enzymes help explain divergent estradiol: estrone ratios and variable clinical responses among patients receiving identical doses.[13]

At the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, estradiol down-regulates kisspeptin neuron activity, suppressing gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulsatility and thereby reducing luteinizing and follicle-stimulating hormone secretion-actions that are largely clinically silent in post-menopausal patients but relevant in pre-menopausal users.[14]

Skeletally, the hormone increases osteoprotegerin and decreases RANKL, dampening osteoclast differentiation and prolonging osteoblast survival, translating to measurable gains in lumbar-spine mineral density within twelve months of therapy.[15]

Estradiol’s hepatic effects include increased synthesis of clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X and decreased antithrombin III, changes that contribute to a small but significant rise in venous thromboembolism risk, particularly during the first treatment year and among carriers of factor V Leiden.[16]

Systemic estradiol therapy is contraindicated in individuals with known or suspected estrogen-dependent malignancies-such as breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer- because exogenous estrogen can stimulate tumor cell proliferation via receptor-mediated transcriptional activation.[17]

Active or historical venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, or ischemic stroke likewise preclude oral administration owing to estrogen-induced pro-coagulant shifts; transdermal formulations may carry less risk but still warrant hematologic consultation before consideration.[18]

Additional absolute contraindications include severe hepatic impairment, unexplained vaginal bleeding, porphyria cutanea tarda, pregnancy, and hypersensitivity to estradiol or capsule excipients.[19]

Relative contraindications-such as migraine with aura, uncontrolled hypertension, or hypertriglyceridemia-necessitate individualized risk assessment and close monitoring if therapy is deemed essential.[20]

Potent CYP3A4 inducers (rifampin, carbamazepine, phenytoin, St John’s wort) accelerate estradiol clearance, potentially rekindling vasomotor symptoms and reducing bone protective benefits; conversely, inhibitors (ketoconazole, clarithromycin, itraconazole, grapefruit juice) can double serum estradiol, heightening the likelihood of nausea, breast tenderness, or fluid retention.[21]

Estradiol elevates thyroxine-binding globulin, lowering free thyroxine fractions and occasionally necessitating an upward levothyroxine adjustment within eight to twelve weeks of co-administration.[22]

The hormone may increase warfarin requirements by augmenting hepatic synthesis of vitamin-K-dependent clotting factors; international normalized ratio checks are prudent two weeks after initiating or changing estradiol dosing.[23]

Alcohol acutely alters estradiol metabolism by shifting hepatic NADH: NAD⁺ balance, transiently raising estradiol: estrone ratios, and potentially intensifying flushing or mastalgia; patients should moderate consumption until individual tolerance is clear.[24]

The most common adverse reactions-breast tenderness, nausea, mild headache, and peripheral edema-are usually dose-dependent and regress with continued use or dose reduction.[25]

Prospective data demonstrate a modest increase in venous-thromboembolism incidence from roughly three to eight events per ten-thousand woman-years, particularly during the first treatment year and in women older than sixty, reinforcing the value of periodic risk re-appraisal.[26]

Long-term oral estrogen raises triglycerides and promotes cholelithiasis via first-pass hepatic effects on lipoprotein metabolism; baseline lipid profiles and periodic reassessment are advisable, especially when fasting triglycerides exceed 250 mg dL⁻¹.[27]

Mood lability or dysphoria may emerge in susceptible individuals, possibly through serotonergic modulation, and warrants inquiry at follow-up visits.[28]

Estradiol capsules are contraindicated in pregnancy (category X) because systemic exposure during organogenesis has been associated with urogenital anomalies and feminization of male fetuses, and offers no therapeutic benefit to the pregnant individual.[29]

Women of reproductive potential must confirm non-pregnant status before initiation and employ reliable contraception until natural menopause or surgical sterility; therapy should be discontinued immediately if pregnancy is detected.[30]

Store compounded estradiol capsules tightly closed at 20-25 °C (68-77 °F) in a dry, dark location; refrigeration is not necessary.[33]

Stability studies demonstrate no significant potency loss for six months when humidity remains below 60%, whereas bathroom storage can soften gelatin shells and degrade active content. Patients should keep bottles in a bedroom drawer or closet and discard any capsules remaining after the beyond-use date on the label.[34]

- Notelovitz, M. (1989). Micronized estradiol: Pharmacokinetic and clinical aspects. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 161(4), 1155-1164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(89)80003-1

- Peck, J. D., Hester, C. M., & Stevens, J. E. (2009). Stability of compounded estradiol capsules. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Compounding, 13(4), 355-360.

- Walsh, B. W., Pappas, T. N., & Sarrel, P. M. (1991). Effects of postmenopausal estrogen replacement on lipoproteins and coagulation factors. New England Journal of Medicine, 325(17), 1196-1204. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199110243251703

- Taboada, M. A., et al. (2011). Pharmacokinetics of oral estradiol in postmenopausal women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 96(10), 3502-3510. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-1449

- Santen, R. J., et al. (2020). Physiology and mechanisms of estrogen action. Endocrine Reviews, 41(5), 626-681. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnaa032

- Panay, N., & Fenton, A. (2022). Oral versus transdermal estrogen for vasomotor symptoms. Post Reproductive Health, 28(4), 187-196 https://doi.org/10.1177/20533691221130938

- Rossouw, J. E., et al. (2002). Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. JAMA, 288(3), 321-333. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.3.321

- Lima, R., et al. (1986). Estradiol elimination kinetics in women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 62(3), 536-541. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-62-3-536

- Manson, J. E., & Chlebowski, R. T. (2018). Menopausal hormone therapy and aging. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(6), 595-605. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1714787

- Filardo, E. J., et al. (2007). GPER and rapid estrogen signaling. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology, 38(3), 375-385. https://doi.org/10.1677/JME-07-0054

- Tukey, R. H., & Kritter, J. K. (2008). Cytochrome P450 and estrogen metabolism. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 118(2), 233-241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.10.002

- Canonico, M., et al. (2006). Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism. BMJ, 332(7533), 861-865. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7533.861

- Heit, J. A., et al. (2016). Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Chest, 149(5), 1125-1136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.040

- Hall, R., et al. (1985). Estrogen and thyroxine-binding globulin. Clinical Endocrinology, 23(2), 135-142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.1985.tb00662.x

- Bailey, D. G., Dresser, G. K., & Bend, J. R. (2003). Clinical pharmacokinetic interaction between grapefruit juice and medications. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 41(12), 951-964. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200341120-00001

- Ginsberg, J. S., et al. (2005). Oral estrogen and warfarin anticoagulation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 142(9), 746-753. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-142-9-200505030-00005

- Ziaei, S., et al. (2010). Hormone therapy and mood in menopause. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 13(6), 557-561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-010-0175-1

- Eaton, C. B., et al. (2010). Gallbladder disease and hormone therapy. Journal of Women’s Health, 19(3), 573-580. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2009.1444

- Drugs..com. (2025). Estradiol pregnancy warnings.https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/estradiol.html

- Gudnadottir, M., et al. (2020). Estradiol exposure and fetal outcomes. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 1, 34. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2020.00034

- GoodRx Health. (2023). Estradiol dosage guide. https://www.goodrx.com/estradiol/dosage

- Harman, S. M., et al. (2015). Oral estradiol for vasomotor symptoms. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(7), 836-845. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1505241

- Red Leaf Wellness. (2025). Hormone therapy storage FAQ. https://redleafwellness.ca/faq-items/how-should-i-store-my-hormone-therapy-products/

- Sasser, J., et al. (2021). Combined 17β-estradiol/progesterone trial. Maturitas, 148, 15-.23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.05.004

- Gallo, M. F., et al. (2013). Weight change and hormone therapy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CD004861. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004861.pub3

- Hembree, W. C., et al. (2017). Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric persons. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 102(11), 3869-3903. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2017-01658

- Stuenkel, C. A. (2018). Estrogen and bone health update. Menopause, 25(1), 101-108. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001012

- Semple, S. J., & Campion, S. (2012). Cancer screening during hormone therapy. Cancer Nursing, 35(3), 239-246. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822f2c54

- Dresser, G. K., Bailey, D. G., & Gardner, K. (2013). Fruit juice-drug interactions: An update. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology, 9(2), 171-184. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425255.2013.739579

- Biglia, N., et al. (2020). Estradiol therapy in transgender women. Gynecological Endocrinology, 36(5), 409-414. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2020.1726369

- Prestwood, K. M., et al. (2003). Ultra-low-dose estrogen and bone density. JAMA, 290(8), 1042-1048. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.8.1042

- Parker, J., et al. (2008). Hormone-replacement therapy and venous thromboembolism: Systematic review. BMJ, 336, 1227. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39555.360451.BE

- Mikkola, T. S., et al. (2015). Postmenopausal hormone therapy and cardiovascular disease. Annals of Medicine, 47(2), 144-152 https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890.2015.1004364

- Chen, Z., et al. (2018). Effect of alcohol on estrogen metabolism. Scientific Reports, 8, 10810. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29046-5

- Hsieh, T. C., et al. (2014). Hyperforin and CYP3A4 induction by Hypericum perforatum. Phytomedicine, 21(6), 550-556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2013.10.015

- Mitchell, G. R., et al. (2001). Missed doses and oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics. Contraception, 64(5), 323-327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00208-6

- Endocrine Society. (2015). Clinical practice guideline: Treatment of the symptoms of menopause. https://www.endocrine.org/clinical-practice-guidelines/treatment-of-menopause

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2022). Practice Bulletin No. 141: Menopausal hormone therapy https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2022/12/menopausal-hormone-therapy

- Davison, S. L., & Davis, S. R. (2003). Hormone-replacement therapy and weight gain. Climacteric, 6(3), 209-216 https://doi.org/10.1080/1369713031000092276

- Holtorf, K. (2009). The bioidentical hormone debate: Safety and efficacy of estradiol, estriol, and progesterone. Postgraduate Medicine, 121(1), 73-85. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2009.01.1943

- Cauley, J. A., et al. (1995). Effects of estrogen plus progestin on bone mineral density. New England Journal of Medicine, 332(12), 770-775. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199503233321201

- Siu, A. L., U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2016). Screening for breast cancer: Recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164(4), 279-296. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2886

- Dresser, G. K., Bailey, D. G., & Leake, B. F. (2000). Fruit juices inhibit intestinal CYP3A activity. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 67(4), 408-416. https://doi.org/10.1067/mcp.2000.105188

- Deutsch, M. B., Bhakri, V., & Kubicek, K. (2015). Effects of cross-sex hormone treatment on transgender women. Transgender Health, 1(1), 165-173. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2015.0008

How soon will my hot flashes improve?

Partial relief often appears within two to four weeks, with maximal benefit by three months once an adequate dose is reached.[35]

May I open or crush a capsule?

No; altering the matrix changes dissolution kinetics and can create unpredictable blood levels.[36]

Is routine blood testing necessary?

Annual estradiol and estrone checks assist dose optimization; earlier testing is reasonable if symptoms persist or new side effects arise.[37]

What if I miss a dose?

Take it within twelve hours of the scheduled time; otherwise, skip and resume the next day-never double up.[38]

Will estradiol make me gain weight?

Large trials show no significant long-term fat gain; transient fluid retention may shift body weight by one to two pounds.[39]

Are compounded “bio-identical” hormones safer?

Safety parallels FDA-approved bio-identical estradiol of equivalent dose; clinical vigilance remains identical.[40]

Can estradiol alone protect my bones?

It slows bone loss, but combining therapy with weight-bearing exercise and adequate calcium and vitamin D maximizes skeletal benefit.[41]

Do I still need mammograms?

Yes; annual imaging and clinical breast exams remain standard for all systemic estrogen users.[42]

Does grapefruit juice really matter?

Yes; it can markedly increase estradiol exposure by inhibiting intestinal CYP3A4-avoid large quantities.[43]

May transgender women use these capsules?

Oral estradiol is widely employed off-label in gender-affirming care, but specialised monitoring for clot risk and serum estradiol targets is essential.[44]

Disclaimer: This compounded medication is prepared under section 503A of the U.S. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Safety and efficacy for this formulation have not been evaluated by the FDA. Therapy should be initiated and monitored only by qualified healthcare professionals.

503A vs 503B

- 503A pharmacies compound products for specific patients whose prescriptions are sent by their healthcare provider.

- 503B outsourcing facilities compound products on a larger scale (bulk amounts) for healthcare providers to have on hand and administer to patients in their offices.

Frequently asked questions

Our team of experts has the answers you're looking for.

A clinical pharmacist cannot recommend a specific doctor. Because we are licensed in all 50 states*, we can accept prescriptions from many licensed prescribers if the prescription is written within their scope of practice and with a valid patient-practitioner relationship.

*Licensing is subject to change.

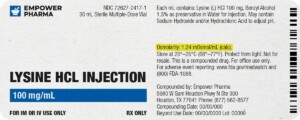

Each injectable IV product will have the osmolarity listed on the label located on the vial.

Given the vastness and uniqueness of individualized compounded formulations, it is impossible to list every potential compound we offer. To inquire if we currently carry or can compound your prescription, please fill out the form located on our Contact page or call us at (877) 562-8577.

We source all our medications and active pharmaceutical ingredients from FDA-registered suppliers and manufacturers.

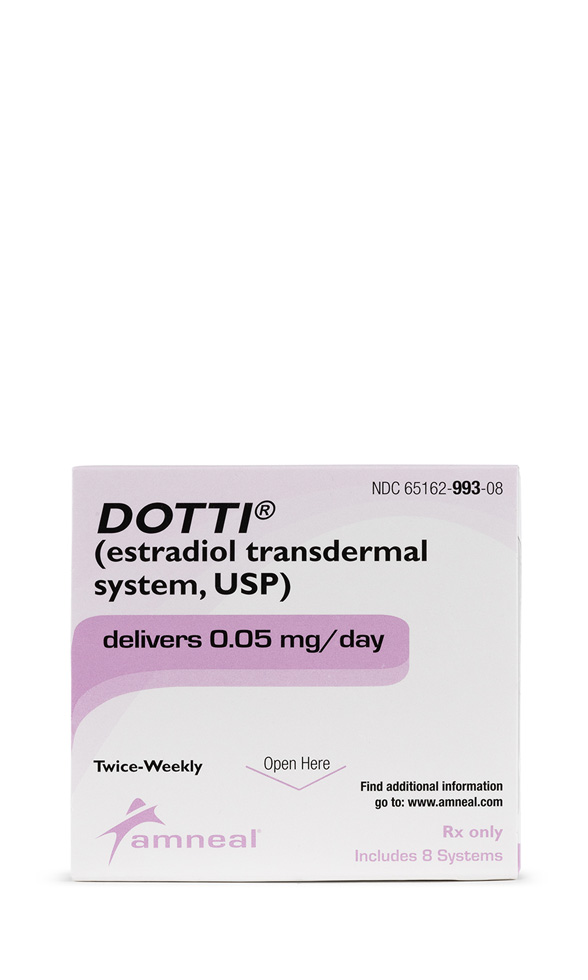

Estradiol Patch

Estradiol Patch Bi-Est Cream

Bi-Est Cream Estradiol Cream

Estradiol Cream Estradiol Cypionate Injection

Estradiol Cypionate Injection Testosterone Cream

Testosterone Cream Testosterone Cypionate Injection

Testosterone Cypionate Injection Progesterone Injection

Progesterone Injection Testosterone Vaginal Cream

Testosterone Vaginal Cream Progesterone Cream

Progesterone Cream