Product Overview

Acne ACNS Gel represents a compounded topical formulation that combines four distinct pharmacological agents azelaic acid, clindamycin, niacinamide, and spironolactone into a single therapeutic preparation designed for the management of acne vulgaris and related dermatological conditions. This multi-ingredient formulation potentially leverages the synergistic properties of each component to address multiple pathophysiological mechanisms underlying acne development, including abnormal keratinization, bacterial colonization, inflammation, and hormonal influences on sebaceous gland activity.[1] The combination of azelaic acid at five percent concentration may provide both antimicrobial and comedolytic effects while potentially addressing post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation that frequently accompanies acne lesions.[2] Clindamycin, present at one percent concentration, serves as a topical antibiotic that specifically targets Cutibacteribacterium acnes, the primary bacterial species implicated in inflammatory acne pathogenesis.[3]

The inclusion of niacinamide at two percent concentration contributes anti-inflammatory properties and may assist in regulating sebum production while potentially improving the skin barrier function that is often compromised in acne-affected individuals.[4] Spironolactone, formulated at five percent concentration for topical application, provides antiandrogenic effects that could potentially reduce sebum production through local inhibition of androgen receptors in sebaceous glands, though the systemic absorption and local efficacy of topically applied spironolactone remain subjects of ongoing clinical investigation.[5] This compounded formulation is prepared under Section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which allows licensed pharmacists to compound medications based on valid prescriptions for individual patients with specific therapeutic needs that may not be adequately addressed by commercially available products.[6]

The gel vehicle selected for this formulation potentially offers several advantages for acne-prone skin, including reduced comedogenicity compared to cream or ointment bases, enhanced penetration of active ingredients through the stratum corneum, and improved patient acceptability due to its lightweight texture and rapid absorption characteristics.[7] The combination approach employed in Acne ACNS Gel may be particularly beneficial for patients who have demonstrated inadequate response to monotherapy or those who present with multiple acne subtypes requiring diverse therapeutic mechanisms.[8] Healthcare providers considering this compounded formulation should conduct thorough patient assessments to determine the appropriateness of each component based on individual patient characteristics, including skin type, acne severity, previous treatment responses, and potential contraindications or sensitivities to any of the active ingredients.[9]

The recommended application protocol for Acne ACNS Gel typically involves once or twice daily application to affected areas, though the specific regimen should be individualized based on patient response, skin tolerance, and severity of the condition being treated.[65] Prior to initial application, patients should cleanse the affected area with a gentle, non-comedogenic cleanser and allow the skin to dry completely, as application to damp skin could potentially increase absorption and the risk of irritation.[66] A thin layer of the gel should be applied to the entire affected area, not just to individual lesions, as the formulation is intended to provide both treatment and prevention of new acne lesions through its multiple mechanisms of action.[67]

The amount of gel required will vary depending on the size of the treatment area, but patients should be counseled that using excessive amounts does not improve efficacy and may increase the risk of adverse effects.[68] For facial application, a pea-sized amount is typically sufficient for the entire face, and patients should be instructed to avoid application to mucous membranes, including the eyes, lips, and inside of the nose.[69] During the initial treatment period, some healthcare providers may recommend starting with every-other-day application or once-daily application in the evening to assess tolerance before advancing to twice-daily use if indicated and tolerated.[70]

The duration of treatment with Acne ACNS Gel may extend for several months, as improvements in acne typically require six to twelve weeks to become apparent, and patients should be counseled about the importance of adherence even in the absence of immediate visible improvement.[71] Patients should be advised to avoid concurrent use of other potentially irritating topical products unless specifically directed by their healthcare provider, as this could compromise skin tolerance and treatment adherence.[72] If excessive dryness or irritation occurs, temporary reduction in application frequency or use of a non-comedogenic moisturizer applied at a different time may help maintain treatment continuity while managing adverse effects.[73]

Special consideration should be given to application in patients with sensitive skin or those using the formulation on areas with thinner skin, such as the neck or chest, where increased absorption and irritation potential may necessitate less frequent application or additional protective measures.[74] The gel should not be applied immediately after shaving or other procedures that might compromise skin integrity, as this could increase absorption and the risk of adverse effects.[75] Patients should be instructed to wash their hands thoroughly after application unless the hands are being treated, and to avoid transferring the medication to other individuals through direct contact.[76]

The therapeutic efficacy of Acne ACNS Gel potentially results from the complementary and synergistic actions of its four active components, each targeting different aspects of acne pathophysiology through distinct molecular mechanisms. Azelaic acid, a naturally occurring dicarboxylic acid, exhibits multiple mechanisms that may contribute to its anti-acne effects, including normalization of epidermal differentiation through modulation of filaggrin expression and reduction of keratinocyte proliferation, which could help prevent the formation of microcomedones that serve as precursors to both inflammatory and non-inflammatory acne lesions.[10] Additionally, azelaic acid demonstrates direct antimicrobial activity against both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, including Cutibacteribacterium acnes and Staphylococcus epidermidis, through potential disruption of bacterial cellular protein synthesis and interference with mitochondrial oxidoreductase activity.[11]

Clindamycin functions as a bacteriostatic antibiotic that binds to the 50S ribosomal subunit of susceptible bacteria, thereby inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis by interfering with peptidyl transfer and preventing elongation of peptide chains, which ultimately leads to suppression of bacterial growth and reduction in the production of pro-inflammatory mediators by Cutibacteribacterium acnes.[12] The topical application of clindamycin may also reduce the concentration of free fatty acids on the skin surface, potentially through both direct antibacterial effects and inhibition of bacterial lipase activity, which could contribute to reduced comedogenesis and inflammation.[13] Furthermore, clindamycin has demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties independent of its antimicrobial effects, including potential suppression of neutrophil chemotaxi s and reduction in the production of reactive oxygen species by activated neutrophils.[14]

Niacinamide, the physiologically active form of niacin, exerts its therapeutic effects through multiple pathways that may be relevant to acne management, including inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production through suppression of nuclear factor-kappa B activation and reduction in interleukin-8 secretion by keratinocytes.[15] This vitamin B3 derivative may also influence sebum production through potential modulation of sebocyte differentiation and lipid synthesis, though the exact mechanisms underlying these effects remain incompletely understood.[16] Additionally, niacinamide could enhance epidermal barrier function through stimulation of ceramide synthesis and acceleration of keratinocyte differentiation, which may help restore the compromised barrier function often observed in acne-affected skin.[17]

Spironolactone, when applied topically, potentially acts as a competitive antagonist at androgen receptors in sebaceous glands, which could theoretically reduce androgen-mediated stimulation of sebum production and sebocyte proliferation, though the extent of local penetration and receptor binding achieved with topical application requires further investigation.[18] The compound may also exhibit mild anti-inflammatory properties through potential inhibition of 5-alpha reductase activity, which converts testosterone to the more potent dihydrotestosterone, thereby potentially reducing local androgen activity in the pilosebaceous unit.[19] The combination of these four mechanisms, antimicrobial action, anti-inflammatory effects, sebum regulation, and hormonal modulation, potentially provides a comprehensive approach to addressing the multifactorial nature of acne pathogenesis.[20]

The use of Acne ACNS Gel may be contraindicated in patients with documented hypersensitivity to any of its active ingredients or excipients, including those with a history of severe allergic reactions to azelaic acid, clindamycin, lincomycin, niacinamide, spironolactone, or any components of the gel vehicle.[21] Patients with a history of regional enteritis, ulcerative colitis, or antibiotic-associated colitis, including Clostridioides difficile-associated diarrhea, should exercise particular caution with topical clindamycin-containing products, as systemic absorption, though generally minimal with topical application, could potentially trigger or exacerbate these conditions.[22] The presence of atopic dermatitis or other chronic inflammatory skin conditions at the application site may represent a relative contraindication, as these conditions could potentially increase systemic absorption of the active ingredients and may be associated with increased risk of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis.[23]

Individuals with severe renal impairment or hyperkalemia should be evaluated carefully before using formulations containing spironolactone, even in topical form, as the potential for systemic absorption, though expected to be limited, could theoretically contribute to electrolyte imbalances, particularly in patients with compromised renal function or those taking other medications that affect potassium levels.[24] The use of this formulation in patients with a history of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency requires careful consideration, as topical clindamycin has been associated with rare cases of hemolysis in susceptible individuals, though this risk appears to be substantially lower with topical compared to systemic administration.[25] Patients with compromised skin barrier function due to severe eczema, extensive wounds, or burns in the treatment area should generally avoid application of this formulation, as increased absorption through damaged skin could potentially lead to unexpected systemic effects.[26]

The concurrent use of this formulation with other topical acne medications, particularly those containing benzoyl peroxide, tretinoin, or other retinoids, may require careful monitoring and potential adjustment of treatment regimens, as combined use could potentially increase the risk of excessive skin irritation, dryness, or other adverse effects.[27] Patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding should consult with their healthcare provider before using this compounded formulation, as the safety of topical spironolactone during pregnancy has not been established, and systemic spironolactone is known to have antiandrogenic effects that could potentially affect fetal development if significant absorption occurs.[28] Additionally, individuals with known sensitivity to sulfites or other preservatives commonly used in topical formulations should verify the complete ingredient list of the compounded preparation, as these excipients could potentially trigger allergic reactions in susceptible individuals.[29]

The potential for drug interactions with Acne ACNS Gel exists through several mechanisms, including local interactions at the application site, systemic interactions following percutaneous absorption, and alterations in skin barrier function that could affect the absorption of other topically applied medications.[30] Concurrent use of topical clindamycin with erythromycin-containing products should generally be avoided due to potential antagonism between these antibiotics, as they compete for the same ribosomal binding site and could potentially reduce the efficacy of both agents when used simultaneously.[31] The combination of this formulation with neuromuscular blocking agents should be approached with caution in patients undergoing surgical procedures, as clindamycin, even when applied topically, could theoretically enhance neuromuscular blockade if significant systemic absorption occurs, particularly in patients with extensive application areas or compromised skin barriers.[32]

Patients using oral potassium supplements, potassium-sparing diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or aldosterone antagonists should be monitored for potential additive effects on potassium levels when using formulations containing topical spironolactone, though the risk of clinically significant hyperkalemia from topical application appears to be minimal based on current evidence.[33] The concurrent use of this formulation with systemic isotretinoin or other oral retinoids may increase the risk of skin irritation and should be carefully monitored, as both azelaic acid and retinoids can cause skin dryness and peeling, potentially leading to excessive irritation when used together.[34] Topical vitamin A derivatives, including tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene, when used concurrently with Acne ACNS Gel, could potentially result in additive irritation, and patients may need to alternate application times or adjust the frequency of use to minimize adverse effects.[35]

The use of abrasive cleansers, alcohol-containing products, or other drying agents in conjunction with this formulation may exacerbate skin irritation and compromise the skin barrier function, potentially altering the absorption characteristics of the active ingredients.[36] Patients using topical corticosteroids in the same area as Acne ACNS Gel application should be monitored for potential alterations in treatment efficacy, as corticosteroids could theoretically mask inflammatory responses while potentially exacerbating acne through various mechanisms including increased comedogenesis.[37] The application of occlusive dressings or moisturizers immediately after Acne ACNS Gel application could potentially increase the absorption of active ingredients, particularly spironolactone and clindamycin, which might increase the risk of systemic effects or local adverse reactions.[38]

Photosensitizing medications, whether topical or systemic, may have additive effects when used with azelaic acid-containing products, as azelaic acid has been associated with mild photosensitivity in some patients, though this effect appears to be less pronounced than with other acne treatments such as retinoids or certain antibiotics.[39] The concurrent use of this formulation with chemical peels, microdermabrasion, or other cosmetic procedures that disrupt the skin barrier should be carefully timed and monitored, as these procedures could potentially increase absorption of the active ingredients and may result in unexpected irritation or other adverse effects.[40]

The application of Acne ACNS Gel may be associated with various local and potentially systemic adverse effects, though the incidence and severity of these effects can vary considerably based on individual patient factors, application frequency, and the extent of the treatment area.[41] Common cutaneous reactions at the application site may include mild to moderate burning, stinging, or tingling sensations, particularly during the initial weeks of treatment, which could potentially affect up to thirty percent of users and typically diminish with continued use as the skin develops tolerance to the formulation.[42] Erythema, dryness, and scaling of the treated skin represent frequently reported adverse effects that may occur with any of the active ingredients, though these effects might be more pronounced with azelaic acid and could potentially be managed through adjustment of application frequency or use of appropriate moisturizers.[43]

Pruritus and skin irritation may develop in some patients, potentially related to individual sensitivity to any of the active ingredients or excipients in the gel vehicle, and these symptoms might necessitate temporary discontinuation or reduction in application frequency.[44] Contact dermatitis, either irritant or allergic in nature, could potentially occur with any component of the formulation, with clindamycin and preservatives in the gel base being among the more common culprits, though the overall incidence of true allergic contact dermatitis to these ingredients remains relatively low.[45] Photosensitivity reactions, though less common with this combination than with some other acne treatments, may occasionally occur, particularly with azelaic acid, and patients should be advised about appropriate sun protection measures.[46]

Systemic adverse effects, while less common with topical application, could potentially include gastrointestinal disturbances such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, or nausea, particularly if significant absorption of clindamycin occurs, though these effects are substantially less frequent with topical compared to oral administration.[47] Headache and dizziness have been reported rarely with topical spironolactone use, though the causal relationship remains uncertain given the expected limited systemic absorption from topical application.[48] Electrolyte disturbances, particularly hyperkalemia, represent a theoretical concern with spironolactone-containing formulations, though clinically significant changes in serum potassium levels have not been consistently demonstrated with topical use in patients with normal renal function.[49]

Paradoxical worsening of acne or development of gram-negative folliculitis may occasionally occur, particularly with prolonged use of topical antibiotics, and could necessitate modification of the treatment regimen or addition of alternative therapeutic approaches.[50] Hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation at the application site has been reported with azelaic acid use, though these pigmentary changes are typically reversible upon discontinuation and may actually represent a beneficial effect in patients with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.[51] The development of antibiotic resistance, while primarily a concern with systemic antibiotics, could potentially occur with prolonged topical clindamycin use and may manifest as reduced treatment efficacy over time.[52]

Pregnancy

The use of Acne ACNS Gel during pregnancy requires careful consideration of the potential risks and benefits, as the safety profile of this specific combination has not been established through controlled studies in pregnant women, and individual components have varying levels of safety data available.[53] Azelaic acid is generally considered to have a favorable safety profile during pregnancy, with minimal systemic absorption following topical application and no demonstrated teratogenic effects in animal studies at doses substantially higher than those achieved with topical use, leading some experts to consider it a reasonable option for pregnant women requiring acne treatment.[54] Topical clindamycin has been assigned to pregnancy category B by historical FDA categorization, indicating that animal reproduction studies have not demonstrated fetal risk, and limited human data suggest no increased risk of major birth defects when used topically during pregnancy, though systemic absorption, albeit minimal, does occur.[55]

Niacinamide, as a water-soluble B vitamin, is generally regarded as safe during pregnancy when used in appropriate doses, and topical application would be expected to result in minimal systemic exposure, though specific safety data for topical use during pregnancy remains limited.[56] The inclusion of spironolactone in this formulation raises particular concerns during pregnancy, as systemic spironolactone has antiandrogenic properties and has been associated with feminization of male fetuses in animal studies, though the risk from topical application would depend on the extent of percutaneous absorption, which has not been thoroughly characterized.[57] Healthcare providers should carefully weigh the severity of the maternal condition against potential fetal risks, considering that untreated severe acne during pregnancy could potentially lead to permanent scarring and psychological distress.[58]

Women of childbearing potential using this formulation should be counseled about the importance of reliable contraception and the need to inform their healthcare provider immediately if pregnancy occurs or is planned during treatment.[59] The first trimester represents a particularly critical period for organogenesis, and extra caution may be warranted during this time, with consideration given to discontinuing the formulation or switching to alternatives with more established safety profiles if pregnancy is confirmed.[60] During the second and third trimesters, continued use might be considered if the benefits clearly outweigh potential risks, though close monitoring and consideration of alternative treatments with better-established safety profiles should remain priorities.[61]

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding considerations also warrant careful evaluation, as clindamycin is known to be excreted in breast milk following systemic administration, though the amounts from topical application would be expected to be substantially lower.[62] The potential for adverse effects in nursing infants, including alterations in gastrointestinal flora or development of antibiotic resistance, should be considered when making treatment decisions for lactating women.[63] Application of the gel to areas that might come into direct contact with the infant, such as the chest or areas where the infant’s face might touch during nursing, should be avoided to minimize potential exposure.[64]

Proper storage of Acne ACNS Gel is essential to maintain the stability and efficacy of its active ingredients throughout the designated beyond-use date established by the compounding pharmacy.[77] The formulation should be stored at controlled room temperature, avoiding exposure to excessive heat or freezing conditions that could potentially alter the physical and chemical properties of the gel matrix or active ingredients.[78] Protection from light may be necessary to prevent photodegradation of certain components, particularly clindamycin and niacinamide, which can be sensitive to ultraviolet radiation, and the medication should therefore be kept in its original container with the cap tightly closed when not in use.[79]

The beyond-use date assigned by the compounding pharmacy should be strictly observed, as the stability of compounded preparations cannot be guaranteed beyond this date, and patients should be counseled to discard any remaining medication after this date has passed.[80] Patients should be instructed to monitor the appearance of the gel for any changes in color, consistency, or odor that might indicate degradation or contamination, and to contact their pharmacist if such changes are observed.[81] The medication should be kept out of reach of children and pets, as accidental ingestion could potentially result in adverse effects, particularly from the clindamycin and spironolactone components.[82]

High humidity environments, such as bathrooms with poor ventilation, should be avoided for storage, as moisture exposure could potentially affect the stability of the formulation and promote microbial growth.[83] The gel should not be transferred to alternative containers, as this could compromise stability, introduce contamination, and result in loss of important labeling information including the beyond-use date and patient-specific instructions.[84] If travel is necessary, patients should be advised to maintain appropriate storage conditions and avoid leaving the medication in vehicles or other locations where temperature extremes might occur.[85]

Healthcare providers and patients should be aware that the physical and chemical stability of this compounded formulation may differ from commercially manufactured products, necessitating more stringent attention to storage conditions and beyond-use dating.[86] The compounding pharmacy should provide specific storage instructions based on the particular formulation and vehicle used, as different gel bases may have varying stability profiles and storage requirements.[87] Documentation of the date of dispensing and opening should be maintained to ensure appropriate use within the established stability window.[88]

- Tanghetti EA. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(9):27-35. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3780801/

- Schulte BC, Wu W, Rosen T. Azelaic acid: Evidence-based update on mechanism of action and clinical application. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14(9):964-968. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26355614/

- Leyden JJ. Antibiotic resistance in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2004;73(6 Suppl):6-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15228128/

- Gehring W. Nicotinic acid/niacinamide and the skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3(2):88-93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00115.x

- Afzali BM, Yaghoobi E, Yaghoobi R, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of 5% topical spironolactone gel and placebo in the treatment of mild and moderate acne vulgaris. J Drug Dermatol. 2012;11(12):1496-1501. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23652948/

- US Food and Drug Administration. Compounding and the FDA: Questions and Answers. 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/compounding-and-fda-questions-and-answers

- Patel NU, D’Ambra V, Feldman SR. Increasing adherence with topical agents for atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(3):323-332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-017-0261-5

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

- Thiboutot D, Dréno B, Sanders V, et al. Changes in the management of acne: 2009-2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(5):1268-1269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.012

- Mastrofrancesco A, Ottaviani M, Aspite N, et al. Azelaic acid modulates the inflammatory response in normal human keratinocytes through PPARγ activation. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19(9):813-820. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01107.x

- Sieber MA, Hegel JK. Azelaic acid: Properties and mode of action. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;27 Suppl 1:9-17. https://doi.org/10.1159/000354888

- Dhawan SS, Thadepalli H. Clindamycin: A review of fifteen years of experience. Rev Infect Dis. 1982;4(6):1133-1153. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/4.6.1133

- Leyden JJ, McGinley KJ, Foglia AN. Qualitative and quantitative changes in cutaneous bacteria associated with systemic isotretinoin therapy for acne conglobata. J Invest Dermatol. 1986;86(4):390-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/1523-1747.ep12285658

- Hoover WD, Davis SA, Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR. Topical antibiotic monotherapy prescribing practices in acne vulgaris. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25(2):97-99. https://doi.org/10.3109/09546634.2013.852297

- Snaidr VA, Damian DL, Halliday GM. Nicotinamide for photoprotection and skin cancer chemoprevention. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60(3):174-180. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajd.13025

- Bissett DL, Oblong JE, Berge CA. Niacinamide: A B vitamin that improves aging facial skin appearance. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(7 Pt 2):860-865. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31732

- Tanno O, Ota Y, Kitamura N, et al. Nicotinamide increases biosynthesis of ceramides as well as other stratum corneum lipids to improve the epidermal permeability barrier. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(3):524-531. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2000.03705.x

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5(3):37-50. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3315877/

- Layton AM. Top ten list of clinical pearls in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34(2):147-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2015.11.008

- Dréno B. What is new in the pathophysiology of acne. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172 Suppl 1:13-19. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.13613

- Wolverton SE, Wu JJ. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.elsevier.com/books/comprehensive-dermatologic-drug-therapy/9780323612111

- Parenti MA, Hatfield SM, Leyden JJ. Mupirocin: a topical antibiotic with a unique structure and mechanism of action. Clin Pharm. 1987;6(10):761-770. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3119170/

- Bikowski J. The use of therapeutic moisturizers in various dermatologic disorders. Cutis. 2001;68(5 Suppl):3-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11730613/

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(9):941-944. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.34

- Beutler E. G6PD deficiency. Blood. 1994;84(11):3613-3636. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V84.11.3613.bloodjournal84113613

- Feldman SR, Careccia RE, Barham KL, Hancox J. Diagnosis and treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(9):2123-2130. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2004/0501/p2123.html

- Krakowski AC, Stendardo S, Eichenfield LF. Practical considerations in acne treatment and the clinical impact of topical combination therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25 Suppl 1:1-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00669.x

- Bagatin E, Costa CS. The use of isotretinoin for acne – an update on optimal dosing, surveillance, and adverse effects. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(8):885-897. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512433.2020.1796637

- Vally H, Misso NL. Adverse reactions to the sulphite additives. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2012;5(1):16-23. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4017440/

- Akhavan A, Bershad S. Topical acne drugs: review of clinical properties, systemic exposure, and safety. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4(7):473-492. https://doi.org/10.2165/00128071-200304070-00004

- Dreno B, Pecastaings S, Corvec S, et al. Cutibacterium acnes (Propionibacterium acnes) and acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(1):5-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14739

- Healy E, Simpson N. Acne vulgaris. BMJ. 1994;308(6932):831-833. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.308.6932.831

- Thiede RM, Rastogi S, Nardone B, et al. Hyperkalemia in women with acne exposed to oral spironolactone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(2):576-577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.057

- Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(1 Suppl):S1-37. https://doi.org/10.1067/mjd.2003.618

- Thielitz A, Abdel-Naser MB, Fluhr JW, et al. Topical retinoids in acne. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6(12):1023-1031. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06741.x

- Mills OH Jr, Kligman AM. Evaluation of abrasives in acne therapy. Cutis. 1979;23(5):704-705. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/156363/

- Kligman AM, Leyden JJ, Stewart R. New uses for benzoyl peroxide: a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent. Int J Dermatol. 1977;16(5):413-417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4362.1977.tb00783.x

- Draelos ZD. The effect of a daily facial cleanser for normal to oily skin on the skin barrier of subjects with acne. Cutis. 2006;78(1 Suppl):34-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16910029/

- Graupe K, Cunliffe WJ, Gollnick HP, Zaumseil RP. Efficacy and safety of topical azelaic acid (20 percent cream): an overview of results from European clinical trials and experimental reports. Cutis. 1996;57(1 Suppl):20-35. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8654128/

- Kessler E, Flanagan K, Chia C, et al. Comparison of alpha- and beta-hydroxy acid chemical peels in the treatment of mild to moderately severe facial acne vulgaris. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34(1):45-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34007.x

- Del Rosso JQ. Topical therapy for acne in women: is there a role for clindamycin phosphate-benzoyl peroxide gel? Cutis. 2014;94(4):177-182. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25372255/

- Bershad S, Kranjac Singer G, Parente JE, et al. Successful treatment of acne vulgaris using a new method. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(4):481-489. https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.138.4.481

- Thiboutot D. Versatility of azelaic acid 15% gel in treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(1):13-16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18246693/

- Matsuoka Y, Yoneda K, Sadahira C, et al. Effects of skin care and makeup under instructions from dermatologists on the quality of life of female patients with acne vulgaris. J Dermatol. 2006;33(11):745-752. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00174.x

- Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, et al. The EAACI/GA²LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2018;73(7):1393-1414. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13397

- Moore A, Ling M, Bucko A, et al. Efficacy and safety of clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% gel for the treatment of acne and acne-induced post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(6):708-713. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22648217/

- Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT, Bojar R, Levy SF. A randomized, double-blind comparison of a clindamycin phosphate/benzoyl peroxide gel formulation and a matching clindamycin gel with respect to microbiologic activity and clinical efficacy in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Clin Ther. 2002;24(7):1117-1133. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80024-6

- Charny JW, Choi JK, James WD. Spironolactone for the treatment of acne in women, a retrospective study of 110 patients. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(2):111-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2016.12.002

- Krunic A, Ciurea A, Scheman A. Efficacy and tolerance of acne treatment using both spironolactone and a combined contraceptive containing drospirenone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):60-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2007.09.024

- Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF. Clinical considerations in the treatment of acne vulgaris and other inflammatory skin disorders. Cutis. 2007;79(6 Suppl):9-25. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17668099/

- Kakita LS, Lowe NJ. Azelaic acid and glycolic acid combination therapy for facial hyperpigmentation in darker-skinned patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(5 Pt 2):817-820. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70359-5

- Eady EA, Gloor M, Leyden JJ. Propionibacterium acnes resistance: a worldwide problem. Dermatology. 2003;206(1):54-56. https://doi.org/10.1159/000067822

- Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs. 2013;73(8):779-787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0

- Chien AL, Qi J, Rainer B, et al. Treatment of acne in pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(2):254-262. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2016.02.150165

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):401.e1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.010

- Bozzo P, Chua-Gocheco A, Einarson A. Safety of skin care products during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(6):665-667. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3114665/

- Kaplan YC, Ozsarfati J, Etwel F, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following first-trimester exposure to topical retinoids. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(5):1271-1276. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14053

- Tyler KH. Dermatologic therapy in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;58(1):112-118. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000089

- Pugashetti R, Shinkai K. Treatment of acne vulgaris in pregnant patients. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26(4):302-311. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.12077

- Law MP, Chuh AA, Lee A, Molinari N. Acne prevalence and beyond: acne disability and its predictive factors among Chinese late adolescents in Hong Kong. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(1):16-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03340.x

- Bettoli V, Zauli S, Virgili A. Is hormonal treatment still an option in acne today? Br J Dermatol. 2015;172 Suppl 1:37-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.13681

- Butler DC, Heller MM, Murase JE. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):417.e1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.009

- Bar-Oz B, Bulkowstein M, Benyamini L, et al. Use of antibiotic and analgesic drugs during lactation. Drug Saf. 2003;26(13):925-935. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200326130-00002

- Leachman SA, Reed BR. The use of dermatologic drugs in pregnancy and lactation. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24(2):167-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2006.01.001

- Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, et al. New insights into the management of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23 Suppl 2:1-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03260.x

- Draelos ZD. Facial hygiene and comprehensive management of rosacea. Cutis. 2004;73(3):183-187. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15074344/

- Goodman G. Cleansing and moisturizing in acne patients. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10 Suppl 1:1-6. https://doi.org/10.2165/0128071-200910001-00001

- Yentzer BA, Gosnell AL, Clark AR, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of strategies to increase adherence in teenagers with acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):793-795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.008

- Green J, Sinclair RD. Perceptions of acne vulgaris in final year medical student written examination answers. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42(2):98-101. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00489.x

- Cunliffe WJ, Gollnick HP. Acne: Diagnosis and Management. Martin Dunitz; 2001. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.3109/9780203450499/

- Baldwin HE. The interaction between acne vulgaris and the psyche. Cutis. 2002;70(2):133-139. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12234155/

- Hayashi N, Akamatsu H, Kawashima M. Establishment of grading criteria for acne severity. J Dermatol. 2008;35(5):255-260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.2008.00462.x

- Katsambas A, Papakonstantinou A. Acne: systemic treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22(5):412-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.03.010

- Dreno B, Poli F, Pawin H, et al. Development and evaluation of a Global Acne Severity Scale (GEA Scale) suitable for France and Europe. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(1):43-48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03685.x

- Koo J. The psychosocial impact of acne: patients’ perceptions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(5 Pt 3):S26-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/0190-9622(95)90417-4

- Bhate K, Williams HC. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(3):474-485. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.12149

- USP General Chapter <795> Pharmaceutical Compounding-Nonsterile Preparations. United States Pharmacopeia. 2023. https://www.usp.org/compounding/general-chapter-795

- Allen LV Jr. The Art, Science, and Technology of Pharmaceutical Compounding. 6th ed. American Pharmacists Association; 2022. https://www.pharmacist.com/Publications/Books/The-Art-Science-and-Technology-of-Pharmaceutical-Compounding-6th-Edition

- Trissel LA. Stability of Compounded Formulations. 6th ed. American Pharmacists Association; 2018. https://www.pharmacist.com/Publications/Books/Stability-of-Compounded-Formulations

- USP General Chapter <1163> Quality Assurance in Pharmaceutical Compounding. United States Pharmacopeia. 2023. https://www.usp.org/compounding/general-chapter-1163

- International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists. IACP Standards of Practice for Compounding Pharmacists. 2022. https://www.iacprx.org/page/standards_of_practice

- Patel VP, Rathod IS. Stability considerations for topical drug products. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2011;73(1):1-6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0250-474X.89751

- Chang RK, Raw A, Lionberger R, Yu L. Generic development of topical dermatologic products. AAPS J. 2013;15(3):674-683. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-013-9472-8

- Marriott JF, Wilson KA, Langley CA, Belcher D. Pharmaceutical Compounding and Dispensing. 3rd ed. Pharmaceutical Press; 2021. https://www.pharmpress.com/product/9780857113856/pharmaceutical-compounding-and-dispensing

- Blessy M, Patel RD, Prajapati PN, Agrawal YK. Development of forced degradation and stability indicating studies of drugs. J Pharm Anal. 2014;4(3):159-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2013.09.003

- Newton DW, Driscoll DF. Chemistry and safety of parenteral nutrition admixtures. Nutr Clin Pract. 2021;36(1):70-87. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncp.10606

- Bajaj S, Singla D, Sakhuja N. Stability testing of pharmaceutical products. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2012;2(3):129-138. https://doi.org/10.7324/JAPS.2012.2322

- ICH Q1A(R2) Stability Testing of New Drug Substances and Products. International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. 2003. https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/Q1A%28R2%29%20Guideline.pdf

- Thiboutot DM, Weiss J, Bucko A, et al. Adapalene-benzoyl peroxide, a fixed-dose combination for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):791-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.006

- Shaw JC. Low-dose adjunctive spironolactone in the treatment of acne in women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(3):498-502. https://doi.org/10.1067/mjd.2000.105560

- Draelos ZD. Cosmetics and dermatologic problems and solutions. 3rd ed. CRC Press; 2011. https://doi.org/10.3109/9781841847405

- Lynde CW, Andriessen A. A cohort study on a ceramide-containing cleanser and moisturizer used for atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2014;93(4):207-213. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24818182/

- Zeichner JA. Optimizing topical combination therapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(3):313-317. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22395581/

- Gollnick HP, Krautheim A. Topical treatment in acne: current status and future aspects. Dermatology. 2003;206(1):29-36. https://doi.org/10.1159/000067821

- Alexis AF, Burgess C, Callender VD, et al. The efficacy and safety of topical dapsone gel 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris in adult females with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(2):197-204. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26885788/

- Elman S, Hynan LS, Gabriel V, Mayo MJ. A systematic review of the effectiveness of topical therapies for pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):46-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.046

- Walsh TR, Efthimiou J, Dréno B. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22(3):13030. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27136626/

- Thiboutot D, Zaenglein A, Weiss J, et al. An aqueous gel fixed combination of clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% for the once-daily treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5):792-800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.040

- Zaghloul SS, Cunliffe WJ, Goodfield MJ. Objective assessment of compliance with treatments in acne. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(5):1015-1021. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06357.x

- Jones-Caballero M, Pedrosa E, Peñas PF. Self-reported adherence to treatment and quality of life in mild to moderate acne. Dermatology. 2008;217(4):309-314. https://doi.org/10.1159/000155641

- Burkhart CG, Burkhart CN. Expanding the microcomedone theory and acne therapeutics. Skinmed. 2007;6(4):163-166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.06243.x

- Kircik LH. Efficacy and safety of azelaic acid (AzA) gel 15% in the treatment of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(6):586-590. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21637900/

- Nast A, Dréno B, Bettoli V, et al. European evidence-based (S3) guidelines for the treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26 Suppl 1:1-29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04374.x

- Haider A, Shaw JC. Treatment of acne vulgaris. JAMA. 2004;292(6):726-735. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.6.726

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, et al. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD003262. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003262.pub5

- Elewski BE. A clinical overview of azelaic acid. Cutis. 2006;77(1 Suppl):12-16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16521157/

- Capitanio B, Sinagra JL, Bordignon V, et al. Underestimated clinical features of postadolescent acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(5):782-788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2009.11.021

- Fabbrocini G, Annunziata MC, D’Arco V, et al. Acne scars: pathogenesis, classification and treatment. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:893080. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/893080

- Saint-Jean M, Khammari A, Seité S, et al. Characteristics of premenstrual acne flare-up and benefits of a dermocosmetic treatment. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27(2):144-149. https://doi.org/10.1684/ejd.2016.2952

- George R, Clarke S, Thiboutot D. Hormonal therapy for acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008;27(3):188-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sder.2008.06.002

- Chularojanamontri L, Tuchinda P, Kulthanan K, Pongparit K. Moisturizers for acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(5):36-44. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4025519/

- Weber MB, Prati C, Soirefmann M, et al. Improvement of pruritus and quality of life of children with atopic dermatitis and their families after joining support groups. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(8):992-997. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02697.x

How long does it typically take to see improvement with Acne ACNS Gel?

Most patients may begin to notice initial improvements in their acne within four to six weeks of consistent use, though optimal results often require twelve weeks or longer of continuous application, as the medication works through multiple mechanisms that require time to manifest visible changes in skin condition.[89] The azelaic acid component may show earlier effects on inflammatory lesions, while the hormonal modulation from spironolactone could take several weeks to influence sebum production.[90]

Can this formulation be used with makeup or sunscreen?

Patients may apply cosmetics and sunscreen after allowing the gel to fully absorb into the skin, typically waiting at least ten to fifteen minutes after application, and should choose non-comedogenic products that won’t clog pores or interfere with the medication’s efficacy.[91] Sunscreen use is particularly important as some components may increase photosensitivity.[92]

What should I do if I experience severe irritation or burning?

If severe irritation occurs, patients should temporarily discontinue use and contact their healthcare provider, who may recommend reducing application frequency, incorporating a gentle moisturizer, or adjusting the formulation strength to improve tolerance while maintaining therapeutic benefit.[93] Mild irritation during the first few weeks is common and often resolves with continued use.[94]

Is it safe to use this gel on sensitive areas like the neck and chest?

Application to sensitive areas may require modified dosing, such as every-other-day application initially or dilution with a non-comedogenic moisturizer, as these areas typically have thinner skin that may be more prone to irritation from the active ingredients.[95] Close monitoring and gradual increase in application frequency may help establish tolerance.[96]

Can this medication be used long-term?

Long-term use may be appropriate for some patients under medical supervision, though periodic evaluation is recommended to assess continued need, efficacy, and potential for antibiotic resistance, particularly regarding the clindamycin component.[97] Some healthcare providers may recommend treatment holidays or rotation with other therapies.[98]

What happens if I miss an application?

If a dose is missed, patients should apply the medication as soon as remembered unless it’s almost time for the next scheduled application, in which case they should skip the missed dose and resume the regular schedule without doubling up on applications.[99] Consistent daily application is important for optimal results.[100]

Can this gel bleach clothing or bedding?

While less likely than with benzoyl peroxide products, some bleaching or discoloration of fabrics may occur, particularly with colored materials, so patients should allow the gel to dry completely before contact with clothing or bedding and consider using white linens during treatment.[101] The azelaic acid component is the most likely to cause fabric discoloration.[102]

Should I avoid sun exposure while using this medication?

While complete sun avoidance isn’t necessary, patients should practice appropriate sun protection including broad-spectrum sunscreen use, protective clothing, and limiting peak sun exposure, as the medication may increase photosensitivity.[103] This is particularly important during the initial treatment period.[104]

Can I use this gel if I have rosacea in addition to acne?

The azelaic acid and niacinamide components may actually provide beneficial effects for rosacea, though patients with this condition may require modified application protocols and close monitoring due to potentially increased skin sensitivity.[105] Healthcare provider consultation is essential for patients with multiple skin conditions.[106]

Is it normal for acne to worsen initially?

Some patients may experience a temporary flare or “purging” period during the first few weeks of treatment as the medication accelerates skin cell turnover and brings underlying microcomedones to the surface, though this typically resolves with continued use.[107] Persistent worsening beyond six weeks should prompt medical reevaluation.[108]

Can men use this formulation despite the spironolactone content?

Male patients can use topical spironolactone-containing formulations, as the systemic absorption from topical application is generally minimal and unlikely to cause the feminizing effects associated with oral spironolactone use.[109] However, extensive application or use on compromised skin barriers should be avoided.[110]

How should I cleanse my skin before applying the gel?

Use a gentle, fragrance-free, non-comedogenic cleanser with lukewarm water, avoiding harsh scrubbing or exfoliating products that could increase irritation when combined with the active ingredients in the gel.[111] Pat the skin dry gently and wait a few minutes before application.[112]

Disclaimer: This compounded medication is prepared under section 503A of the U.S. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Safety and efficacy for this formulation have not been evaluated by the FDA. Therapy should be initiated and monitored only by qualified healthcare professionals.

503A vs 503B

- 503A pharmacies compound products for specific patients whose prescriptions are sent by their healthcare provider.

- 503B outsourcing facilities compound products on a larger scale (bulk amounts) for healthcare providers to have on hand and administer to patients in their offices.

Frequently asked questions

Our team of experts has the answers you're looking for.

A clinical pharmacist cannot recommend a specific doctor. Because we are licensed in all 50 states*, we can accept prescriptions from many licensed prescribers if the prescription is written within their scope of practice and with a valid patient-practitioner relationship.

*Licensing is subject to change.

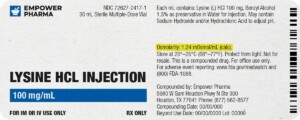

Each injectable IV product will have the osmolarity listed on the label located on the vial.

Given the vastness and uniqueness of individualized compounded formulations, it is impossible to list every potential compound we offer. To inquire if we currently carry or can compound your prescription, please fill out the form located on our Contact page or call us at (877) 562-8577.

We source all our medications and active pharmaceutical ingredients from FDA-registered suppliers and manufacturers.

Acne Extreme Gel

Acne Extreme Gel Acne DNS Gel

Acne DNS Gel Acne Ultra Gel

Acne Ultra Gel Anti-Aging Vita Gel

Anti-Aging Vita Gel GHK-Cu Facial Serum

GHK-Cu Facial Serum Anti-Aging Siro Gel

Anti-Aging Siro Gel Tretinoin TAAN Cream

Tretinoin TAAN Cream NAD+ Cream

NAD+ Cream Doxycycline Tablets

Doxycycline Tablets